Ezra Stoller Furniture

Ezra Stoller had such a profound impact on the field of modern architectural photography that his name became a verb. Famous architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Eero Saarinen and Marcel Breuer saw their buildings “Stollerized” — a word coined by none other than Philip Johnson, denoting expertly reimagined for the flat space of the photograph and made accessible to readers of books and magazines who could not visit them in person.

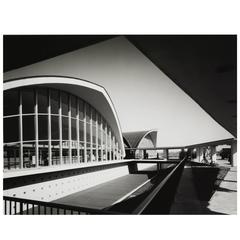

Stoller’s mostly black-and-white photographs play up the most exciting features of 20th-century landmarks: the swooping curves of Saarinen’s TWA Terminal (1962), the radical transparency of Johnson’s Glass House (1949), the monolithic gravitas of the United Nations Building (1950). As the photographer once said, “While I cannot make a bad building good, I can draw out the strengths in a work that has strength.”

Although he didn’t have an architecture degree, Stoller, who died in 2004 at age 89, very nearly joined the profession. He was enrolled in architecture school at New York University when he began taking photographs in the late 1930s. This side project soon became a full-time career, as his classmates and professors (including Edward Durell Stone) started giving him assignments.

By 1946, he was traveling around the country documenting major projects for Fortune magazine, including Wright’s Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, Arizona. This was the beginning of a long association with Wright, who later commissioned Stoller to shoot the Guggenheim Museum and the house perched above a waterfall known as Fallingwater.

Stoller had an equally symbiotic relationship with Saarinen, capturing many of the low-slung, boxy structures the Finnish architect designed for Midwestern corporate campuses, as well as his more fanciful TWA Terminal at Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport), in New York.

For someone so strongly aligned with modern architecture, Stoller acknowledged some surprising historical influences. One was the visionary 18th-century printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who, like Stoller, trained in architecture. Another was the late-19th-century photographer Eugene Atget, who documented the streets and storefronts of Paris during a major upheaval in urban planning.

“For getting a sense of space, there’s nobody like Atget,” Stoller once told an interviewer.

In addition to Stoller’s artistry, architects appreciated his meticulous multistage process. Typically, he would start with a daylong walk-through of a project, after which he formulated a detailed shooting plan — annotating images of the building with arrows and times of day and paying close attention to the weather and changing light.

Once onsite with his equipment, Stoller would rearrange the furniture to achieve the perfect shot and obsess, as he later recalled, over such questions as “at exactly what angle should the window be open.”

Find original Ezra Stoller photography on 1stDibs.

20th Century American Ezra Stoller Furniture

Paper

Late 19th Century French Victorian Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Iron

20th Century French Other Ezra Stoller Furniture

Oak, Walnut

17th Century English Renaissance Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Oak

Late 19th Century French Victorian Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Iron

20th Century American Organic Modern Ezra Stoller Furniture

Paper

20th Century American Mid-Century Modern Ezra Stoller Furniture

Brass

15th Century and Earlier German Medieval Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Wood, Paint

18th Century and Earlier Portuguese Baroque Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

16th Century Italian Baroque Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Iron

Early 1900s French Beaux Arts Antique Ezra Stoller Furniture

Ormolu

Mid-20th Century Ezra Stoller Furniture

Porcelain

Late 20th Century American Mid-Century Modern Ezra Stoller Furniture

Brass