In 2007, the sci-fi author William Gibson published a novel titled Spook Country. Set in and around contemporary Los Angeles, it told the story of a group of artists who place virtual 3D sculptures — a monstrous squid, the bodies of dead celebrities — in geotagged locations throughout the city.

Although not the most influential of Gibson’s works, Spook Country was prescient in its anticipation of an art culture made possible by merging the world we experience through our ordinary senses with the heretofore invisible world of the Internet, a species of experience that would come to be known as augmented reality, or AR.

In keeping with Gibson’s dictum that “the future is already here, just unevenly distributed,” nearly all the technology needed for the AR apparatus of Spook Country was available around the time of the novel’s publication. But the melding of this imagined reality with our own has been less than seamless.

That could change with the release of Apple’s AR glasses, rumored to be arriving sometime in the next year or so. Apple has been backing AR since 2017, and the launch of a popular standalone device might kick-start the market for AR, much as the launch of the iPad created the consumer appetite for larger tablets in 2010.

Such an event could also create an opportunity for NFTs to find a place in our homes as 3D objects, bearing the same relation to 2D NFTs as sculpture does to painting. In fact, many cryptoartists already use virtual-reality tools in their practice, giving their pieces a paradoxically hands-on feel, much closer to sculpture than images produced with a stylus or on a screen.

Ogi Damyan, a Bosnian-born, United Kingdom–based artist who creates under the name OgiWorlds, spends 6 to 12 hours a day in a virtual-reality studio building the environments that form the basis of his work. “There’s so much joy in creating in VR because you make a mark and it’s there, it exists in the room,” he says. “But it’s also the closest thing I could equate to play.”

In his piece CHORISMOS TECHNE, 2021, which sold on 1stDibs last year for Ξ19.1000 ($61,152.28), androids dance in a kind of ritualistic celebration of a monumental robotic birth. Damyan describes being heavily influenced by the Japanese anime that was imported into the Balkans of his childhood.

Often hastily translated or retrofitted with new storylines by writers who had no understanding of the original Japanese, the animations gave him a sense of contact with a fragmented mythology, one that demanded that viewers use their imagination to fill in the gaps. It’s that kind of partly occluded story, or metanarrative, that Damyan hopes to re-create through the constellation of pieces derived from the CHORISMOS universe.

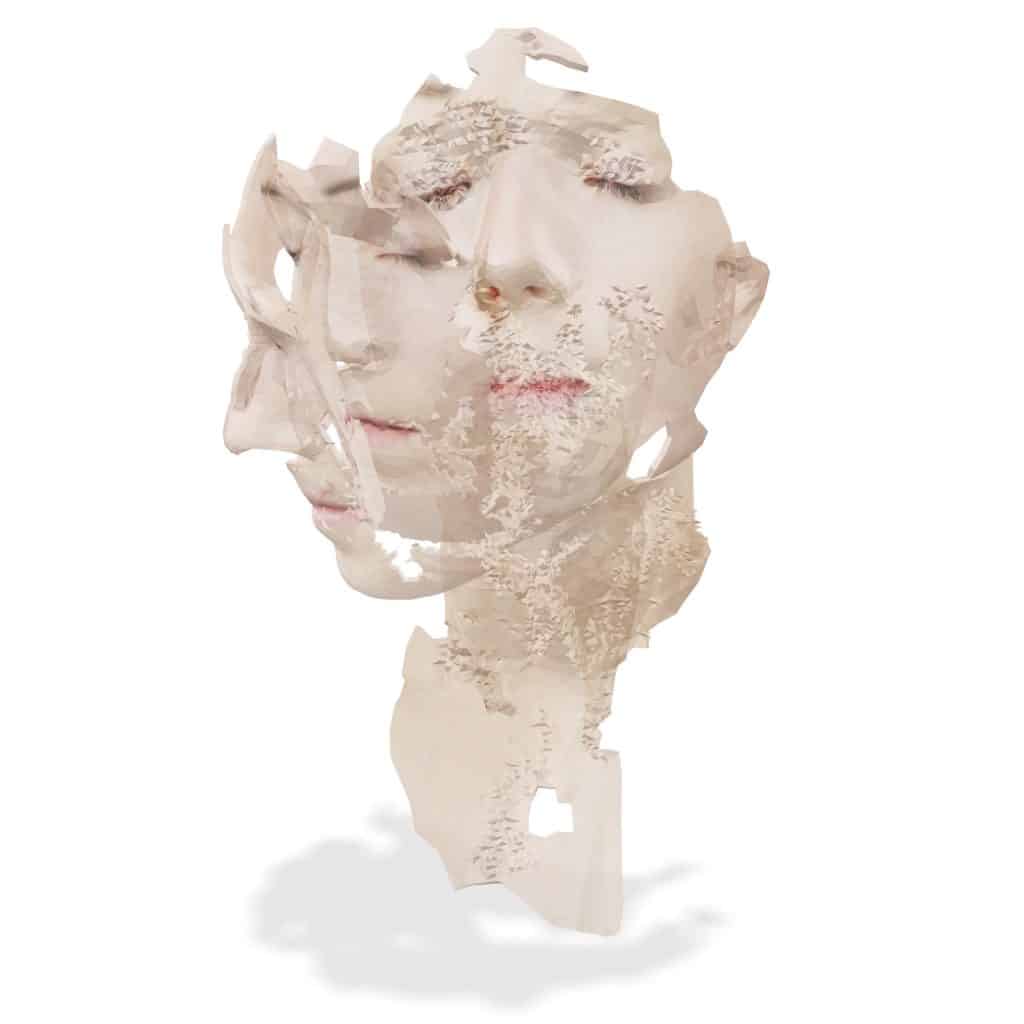

Damyan constructs his objects at human scale, stacking individual elements in 3D space and even applying microscopic textures to their surfaces. Some pieces are built to loom over the human viewers, like the giant head in ZENITH, which stands nearly 100 (virtual) feet tall. Working at this scale makes the viewers’ experience of his world far more visceral.

“I did a project where there was a tower that was 723 meters [2,372 feet] tall, and standing on top of it looking down, I realized my hands were sweaty,” he says. This level of verisimilitude is relatively common in movie production and video gaming, but the NFT market allows an artist like Damyan to pursue his idiosyncratic vision through the unique means of VR.

The medium is also inspiring creators more inclined to the intricate than the monumental. Marc-O-Matic is an Australian artist who creates minutely detailed works in AR and VR, often transforming complex biological structures into mechanical systems. There are heads filled with Numbskulls-style homunculi, metallic skulls with electronic eyeballs and elephants constructed like steampunk traction engines.

For his public appearances (and, indeed, our interview), Marc-O-Matic wears an augmented-reality mask, which turns his face into a Benno von Archimboldi–style accretion of architectural features, topped by a hat resembling the dome of Melbourne’s Flinders Street station and circled by a helicopter. “I just wanted to embody where I’m from and put that forward and put me in the back,” he explains, ”like the Wizard of Oz.”

Like Damyan, he has a particular affinity for AR and VR because of his love of world building. One of his most recent pieces, created in his role as Adobe’s AR ambassador, is Junk Age: Remember the Yesterbeasts, a postapocalyptic trash heap populated by creatures who have emerged from the garbage. He describes the work as a “markerless” experience that “exists wherever you put it. If you put it on the table, it works on the table. It will respond to whatever environment it’s in.”

This interaction between the real and the imaginary gives the piece an extra layer of magic; it’s more than mere superimposition, not just the frank surreality of a whale floating across your living room but the especially hard-to-compute fact of the virtual whale responding to the real world around it.

Of course, the placement of AR artworks like these opens an array of opportunities. Not only can they be scaled to fit your home, so that an ordinary domestic environment is transformed into a gallery space simply by your putting on a pair of glasses, but they also offer the ability, à la Spook Country, to attach works to particular geolocated coordinates.

One such piece is Angie Taylor’s virtual sculpture titled Mammon. Based on a 19th-century painting of the same name by George Frederic Watts, which depicts a statue he planned to commission but never executed, it takes the allegorical figure Mammon, representing human greed and material acquisition, and reworks it in what Taylor calls a “virtual bronze.”

An artist and prop maker, Taylor learned to sculpt from wood carvers on Jamaica’s beaches in the 1970s. “I like to try and leave the mark of the the digital on it, in the same way that when you’re carving you leave the mark of the chisel,” she says.

Taylor is heavily influenced by her experience of the UK punk scene in the late 1970s. That perhaps explains why Watts’s planned sculpture, originally designed for London’s Hyde Park, spoke to her. “It just seemed appropriate at the time, because there was a lot of people who were just obsessed with money getting into cryptoart,” she says.

The piece can work at coffee-table scale, but Taylor has also experimented with more provocative sizes and locations. “I took it down to my local beach,” she says. “I scaled it up, and I put it on the sea, and it looked amazing.”

She admits she’s also been buying plots of metaverse real estate on the platform Superworlds, including the steps of the Tate museum in London (where, not coincidentally, Watts’s painting resides). “So, I could put it there, which would mean that anyone who goes would see Mammon on the steps of the Tate gallery.”

And what could be more punk than that? Fifteen years on, perhaps Gibson’s timeline is finally about to merge with our own.