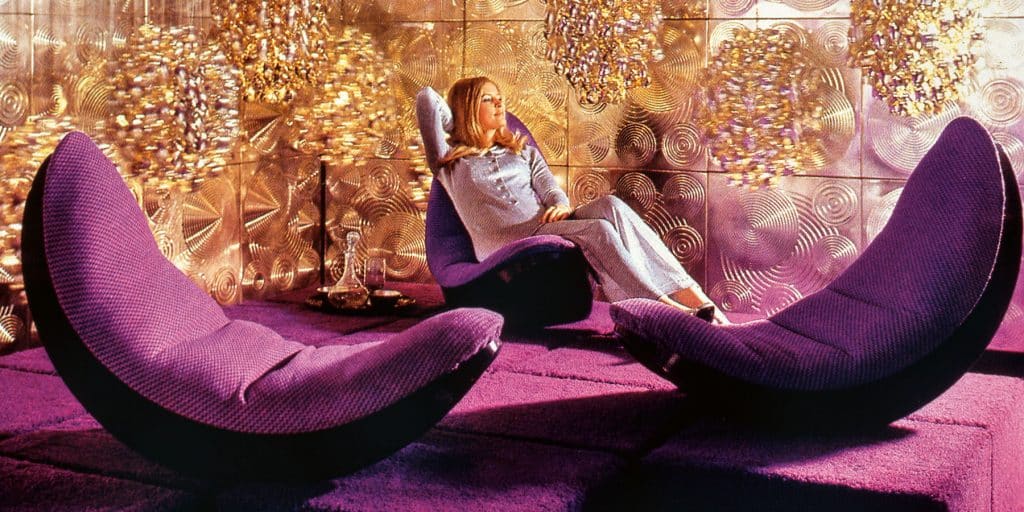

October 14, 2018Featured recently in Dries Van Noten and Prada men’s runway collections, the work of mid-century Danish designer Verner Panton — seen here in 1965 with one of his mirrored Spiegel sculptures — is having a renaissance (photo © Panton Design, Basel/Archive Vitra, Design Museum, Weil am Rhein). He’s now subject of a beautiful new book, released by Phaidon, which showcases images of the installation he created for the Cologne Furniture Fair in 1970 (top; photo © Panton Design, Basel/Illums Bolighus).

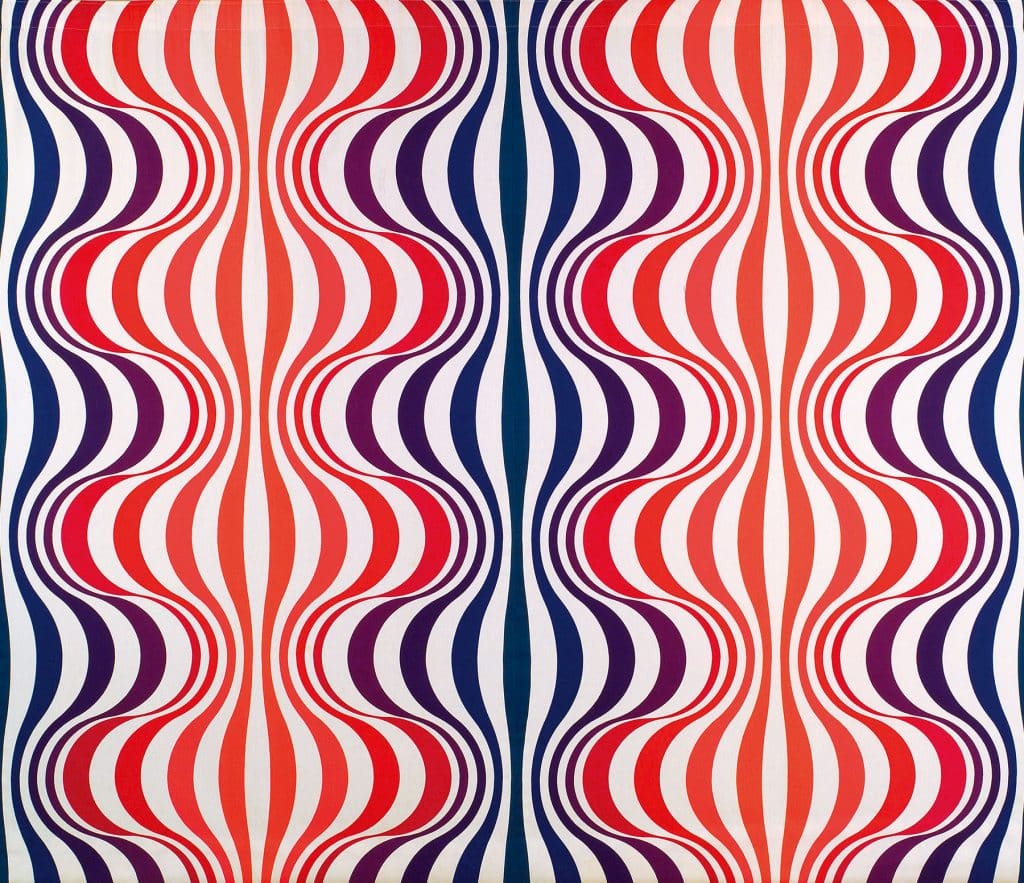

Verner Panton had a hand in Dries Van Noten’s Spring/Summer 2019 menswear collection — his right hand, to be precise. It makes a graphic appearance on the breezy button-downs and chic sweatshirts that Van Noten debuted in Paris this past June. The giant disembodied palm, borrowed from Panton’s Anatomical Designs textiles (1968), is joined in the collection by the boldly colored squiggles and trippy swoops he created in the late 1960s and early ’70s for the Swiss textile firm Mira-X. Panton was just as prominent on the Prada runway in Milan, where guests at June’s Spring 2019 men’s show perched on his transparent inflatable stools, a 1954 design reissued for the occasion.

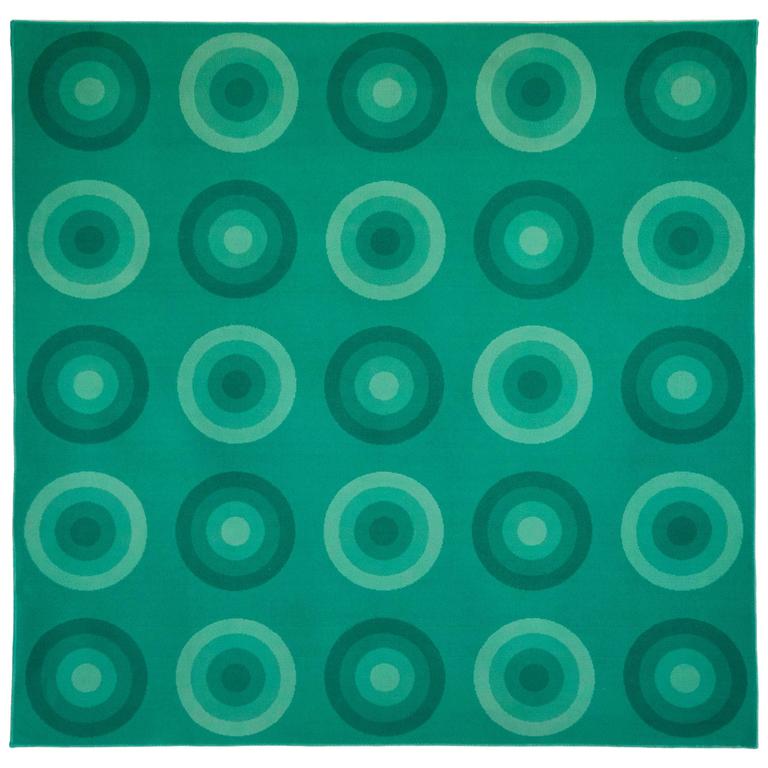

Fifty years after the debut of his namesake S-shaped molded-plastic chair and 20 years after his death, in 1998, at the age of 72, Panton’s bold colors, biomorphic forms and unconventional materials remain invitations to explore new ways of living. Fresh nostalgia for this groovy brand of futurism is bound to be fueled by a new monograph, published by Phaidon and authored by Danish scholars Ida Engholm and Anders Michelsen. Containing a veritable trove of archival photographs, advertisements and sketches, the glossy red hardcover considers the trailblazing designer in sections investigating the themes of environments, colors, systems and patterns.

“While being immersed in both postwar utilitarian design culture and nineteen-sixties pop culture, Panton developed a personal and quite unique language that became timeless and incredibly influential,” says Phaidon publisher Emilia Terragni. “The book shows how Panton’s signature design developed in connection with the discovery of new technology and materials, and how his design was created to fit a modern way of life — full of flair and freedom from tradition.”

Left: In an image from 1967, Marianne Panton, the designer’s wife, sits on a Panton chair with his Shell lamp hanging above and a Unika Vaev rug below. Marianne collaborated with Vitra on the design of the anniversary-edition Glow version of the seat (photo © Panton Design, Basel). Right: Dries Van Noten debuted pieces with Panton’s patterns on them in his Spring/Summer 2019 menswear show in Paris in June (photo by Victor Virgile).

Born on February 13, 1926, to a couple of innkeepers on the Danish island of Funen, Panton trained as a builder at a local technical college before studying architecture at Copenhagen’s Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. There, he found mentors in the now-legendary Danish modern designers Poul Henningsen (to whose stepdaughter he was briefly married) and Arne Jacobsen (whom he met while dining chez Henningsen).

“Several of Panton’s environmental product images almost resemble stills from a science fiction movie,” the book’s authors, Ida Engholm and Anders Michelsen, write. “Depicted here is the Panthella lamp in a white interior layout that would not have seemed amiss in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.” Photo © Panton Design, Basel

During his apprenticeship with Jacobsen, from 1950 to 1952, he worked on the iconic Ant chair. “It was a meeting between what was, at that time, the all-defining International Style, which Jacobsen was tirelessly propagating in Denmark, and an experimental sensibility, which Panton shared with Henningsen,” Engholm and Michelsen write of the Ant.

Panton’s first commercial design was a button-less shirt that could be pressed with a rotary iron. He sold the patent to a shirt factory, invested the proceeds in a Volkswagen minibus, which he and a friend transformed into a mobile design studio, and road-tripped around Europe, gathering inspiration and contacts along the way. (The puckish Dane was an inveterate networker.) Early seating experiments soon yielded success, as Fritz Hansen began producing his steel-framed Bachelor and Tivoli chairs in 1955.

Another breakthrough came three years later when Panton renovated the Danish inn managed by his father, designing everything from a two-story annex (in concrete, wood and glass) to the staff uniforms (in five shades of red). The holistic endeavor also marked the introduction of his Cone chair. Fabricated from a sheet of conically folded tin padded with foam rubber and upholstered in wool, it was snapped up by an entrepreneur who made it the foundation of a new furniture company, Plus-linje.

With his predilection for Plexiglas armchairs, modular-cube furnishings and pairing red with orange — an enemy of neutrals, he dressed in shades of blue and once called for a tax on white paint — Panton was not a natural fit for the land of finely crafted teak forms. “Danish design, for me, is [Finn] Juhl, [Hans] Wegner, [Børge] Mogensen and a few others. They were incredibly talented, but we didn’t have much in common. It just wasn’t me,” Panton once wrote. “I’ve always tried to find other paths. It’s an urge I have not been able to resist.”

One such path led to Basel, Switzerland, where he had a fateful meeting with Vitra cofounder Willi Fehlbaum. Panton brought a small model of a curvy, plastic, one-piece chair. “He had been traveling with this thing all through Germany, showing it to manufacturers, and nobody was interested. They told him to forget it. And then he met my father,” recalls Fehlbaum’s son, Rolf, now chairman emeritus of Vitra. “At that time, we had never done something ourselves, because we were producing [under license from Herman Miller] the Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson products that had been developed in the USA.” In 1963, the Fehlbaums decided to invest in the concept, and Panton moved to Basel.

“It turned out to be a nearly impossible challenge,” says Eckart Maise, Vitra’s chief design officer, “as the bold contours imagined by the designer had to be reconciled with the physical limits of plastics technology and manufacturing requirements.” After several years of research, development and discarded designs, a final set of 10 manually laminated, glass-fiber-reinforced polyester prototypes culminated in the first all-plastic cantilever chair to be manufactured in one piece. The Panton chair was introduced to the public in 1968, at the imm furniture fair, in Cologne. “Its sculptural shape in Panton’s trademark vibrant colors caused quite a sensation in the late nineteen-sixties — and still do,” says Maise.

“In accordance with contemporary demands for economizing on space,” the authors write of Panton’s 1966 multifunctional living unit, “the design offered opportunities for dining, relaxing and resting on several levels, all contained within one and the same piece of furniture.” Photo © Panton Design, Basel

“Look at Gerrit Rietveld’s famous Zig-Zag chair. Panton turned it into an amorphic, colorful sculpture,” says Evan Snyderman, cofounder of New York’s R & Company gallery, a pioneering exhibitor of Panton’s work in the United States. “At this point, almost everyone has seen a Panton chair, even if they don’t know who Panton is. It has always represented the future, as a lot of his work did.”

Vitra is celebrating the Panton chair’s 50th anniversary with two limited-edition versions, released earlier this year. Panton Chrome realizes the mirror effect that the designer had explored giving the chair’s surface in the early 1970s; the luminous Panton Glow, developed in consultation with Panton’s widow, Marianne, is varnished by hand with phosphorescent pigments, which are sealed with a glossy protective layer.

Marianne and Vitra were also instrumental in the Dries Van Noten collaboration. (The furniture company’s design museum, in Weil am Rhein, Germany, is home to Panton’s archives and much of his oeuvre.) Carin Panton von Halem, the Pantons’ daughter, worked with Van Noten’s team and the museum staff to select textile designs that were appropriate for garments; each piece will be co-labeled. “I am very proud that Verner’s color systems and patterns have become a source of inspiration for Dries Van Noten and his latest collection,” Marianne says. “These creations breathe new life into his textile designs and prove that they are still relevant today.”

The designer’s iconic S-curve Panton chair — the world’s first all-plastic cantilevered seat, produced over the decades in a variety of colors — debuted 50 years ago. To celebrate the piece’s semicentennial, Vitra has released two limited-edition versions: Chrome, with a mirrored surface, and Glow, with a phosphorescent finish. Photo courtesy Archive Vitra, Design Museum, Weil am Rhein

Panton poses in his wood-framed, wool-upholstered Living Tower, from 1968, which the authors describe as “a sculptural piece of furniture” consisting “of two elements with four seats on different levels.”

The enduring appeal of all things Panton comes as no surprise to consummate fan Miles Redd. “He saw what the zeitgeist wanted way ahead of time,” notes the interior designer. Redd has a Panton Shell lamp hanging above the breakfast table of his New York apartment. “It always makes me smile,” he says of the luminous, chain-linked constellation of mother-of-pearl discs, introduced in 1966 and inspired by wind chimes made by fishermen in India’s Andaman Islands.

Panton himself lived with an immersive version of the design, having adorned the ceiling of his dining room in Binningen, Switzerland, with 100,000 shells dangling in tiers like illuminated stalactites. That legendary ceiling lamp recently emerged from 30 years in storage. After a painstaking restoration by Basel architecture firm Sauter von Moos, it was installed (in 52 parts) in the Kunsthalle Basel’s restaurant, where it remains on long-term loan from the Panton family. “It’s one of those things that when you see a photograph of it in Panton’s home, you gasp and say, ‘Whatever happened to that!?’ ” remarks Snyderman, who visited the work in Basel over the summer. “And now, you can go see it. It’s phenomenal.”

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

Shop Verner Panton on 1stdibs