May 9, 2021As museums across the country have been taking stock of the lack of work by women artists and people of color on their gallery walls, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta presents an institutional critique of its own renowned photography holdings in “Underexposed: Women Photographers from the Collection,” on view through August 1.

The exhibition is organized by Sarah Kennel, curator of photography at the High, who did a deep dive into its collection of 8,600 prints after joining the museum in 2019. She discovered that 26 percent of the artists represented were women and a far greater percentage of their images had not been on view since at least 2000, when the museum started keeping digital exhibition display records.

“It’s important that as we collect work, we also get behind the work we collect and take the opportunity to exhibit it,” Kennel says. She has flagged every image not publicly seen since 2000 or earlier with an asterisk on its exhibition label — encompassing more than half of the 106 works in the show, by artists including Ruth Bernhard, Barbara Morgan, Svjetlana Tepavcevic, Hellen van Meene, Lisa Kereszi, Elizabeth Turk and Joni Sternbach, among the 86 photographers represented.

Rather than a comprehensive survey of photography by women, Kennel has underscored themes that surfaced from the collection. The first section, called “Pioneers to Professionals,” focuses on images made in the early half of the 20th century with the global emergence of the independent “new woman.” “Changes in camera technology and in social and political culture opened up spaces for women photographers, particularly with the rise of the illustrated press, fashion magazines and photojournalism,” says Kennel.

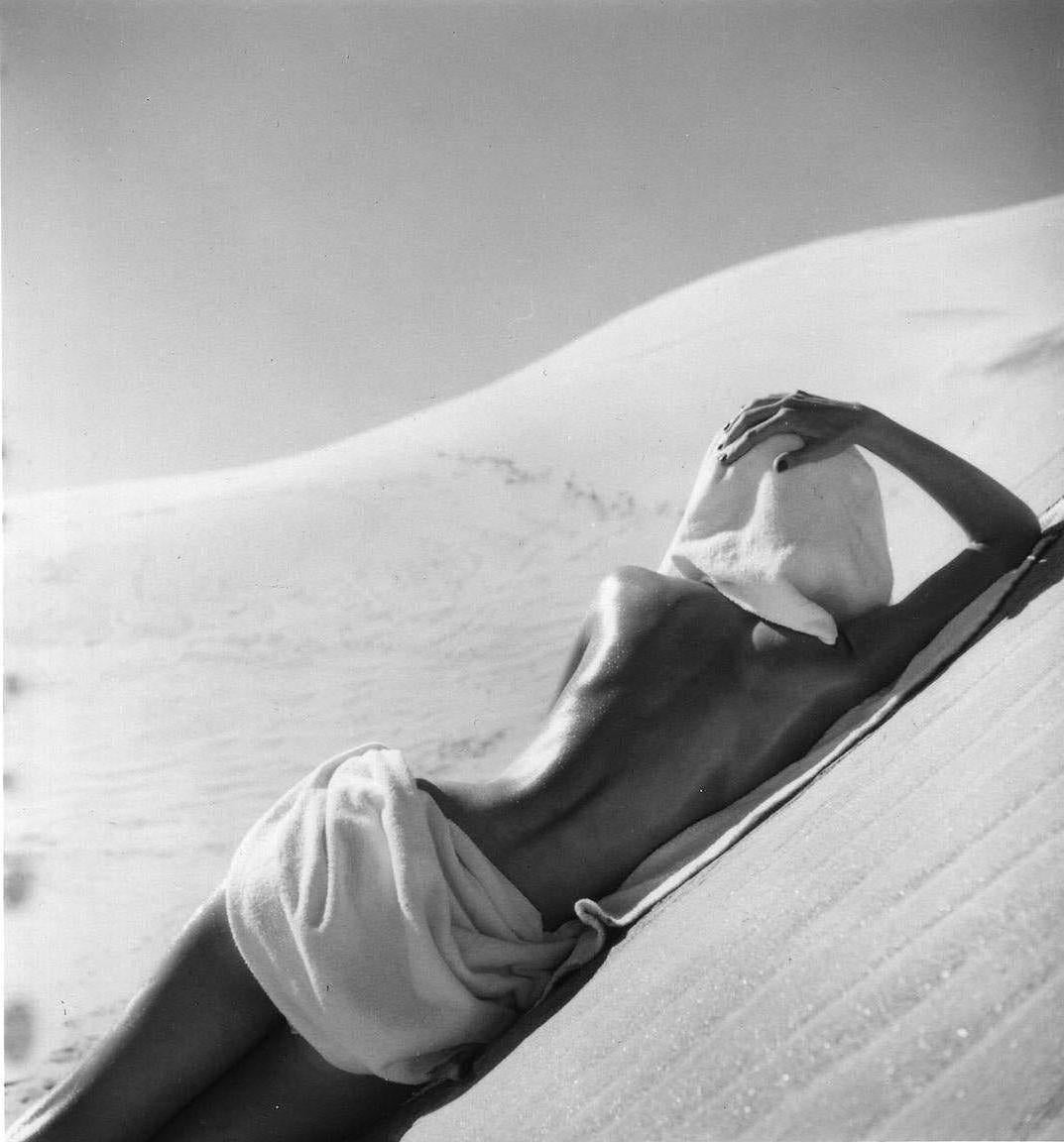

Here, she has included photographers such as Berenice Abbott, known for documenting New York in the 1930s; Margaret Bourke-White, the first staff photographer for Fortune magazine; the West Coast modernist Imogen Cunningham, who was inspired by seeing the expressionistic portraits of Gertrude Kasebier; Dora Maar, better known for her relationship with Pablo Picasso than her own art; and Louise Dahl-Wolfe, the first female photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, who worked with editor-in-chief Carmel Snow and fashion editor Diana Vreeland.

“Magazines realized that women could market to women,” says Kennel, who has spotlighted the networks of women who supported each other in the artist biographies included on each label.

In work starting in the 1970s, when photographic practices began being introduced in a variety of art schools, Kennel noticed women often leading the way in alternative-process photography and gathered examples in the section “Experimenters.” Olivia Parker, for instance, made complex constructions of natural and found objects and photographed them in her home studio while raising two children in the 1970s and ’80s. “She was responding to the opportunity and also limitations she had being a working parent,” says Kennel.

In her cameraless cyanotype from 2018, Meghann Riepenhoff exposed her sheet of light-sensitive paper to the ocean waves, creating a large-scale abstraction of nature that bookends an early 1850s cyanotype of foliage by Anna Atkins in the show.

The section “Deconstructing the Domestic” showcases contemporary artists reflecting on domesticity, whether Sarah Hobbs’s view of a bathroom interior with the mirror obscured by thousands of paper cutout butterflies or Sandy Skoglund’s darkly humorous tableau of a suburban patio overrun by frightening black squirrels.

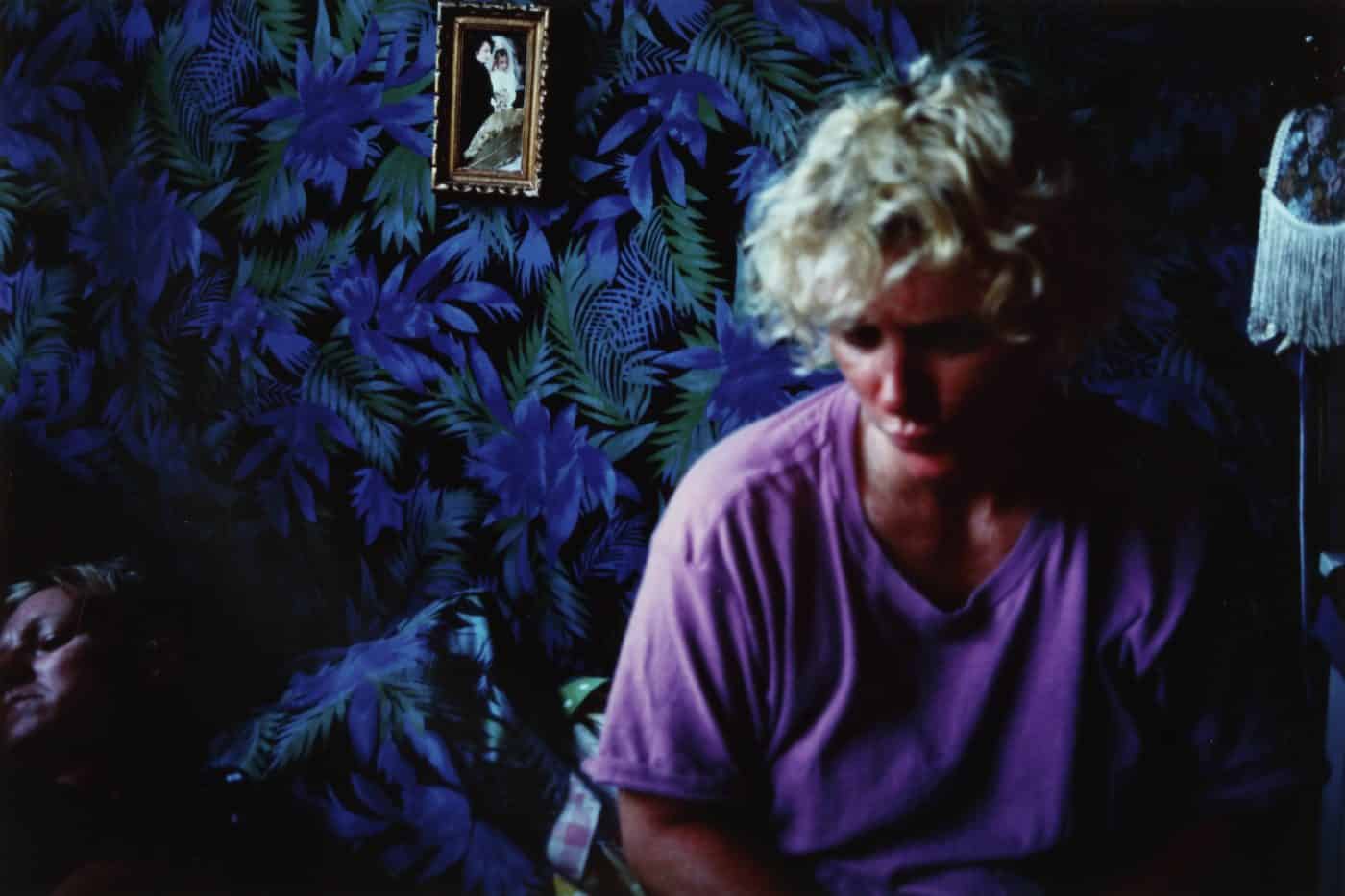

“Women Looking at Women” is the section most sprawling in time frame, with artists including Helen Levitt, Mary Ellen Mark and Sally Mann photographing young girls and adolescents. Nan Goldin conveys the beauty and vulnerability of her friends, Susan Meiselas looks critically at the sexualization of women in her series on carnival strippers and Marilyn Minter appropriates sexualized representations as a source of female empowerment and pleasure.

“It’s not really proposing that there is a female gaze,” says Kennel. Rather “it’s asking the viewer to think about how portraiture in general is structured. What are the relationships between maker and sitter? Does gender make a difference in terms of the response to the photographer?”

And what if the sitter is the photographer? “Strategies of Identity,” the final section of the show, looks at photographic self-portraiture as a key strategy for women artists to disrupt stereotypes of gender and race, including Zanele Muholi‘s arresting self-portrait challenging conventionally exoticized depictions of Blackness and one from Cindy Sherman’s early performative “Untitled Film Stills” series, showing her in the guise of a Hollywood starlet.

Mickalene Thomas’s image Les Trois Femmes Deux (2018) shows herself with two other Black women adapting the picnicking scene from Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862–63. “She’s reclaiming this iconic image in art history and centering Black female subjectivity,” Kennel says.

While photography is a huge part of both Thomas’s and Minter’s practices, with even their paintings starting with photography, both artists are situated more in the context of contemporary art than in photography, says Carla Camacho, a partner at Lehmann Maupin, which represents them both.

Noting their “star power,” Camacho says these two artists “have the luxury of being able to vacillate between the two worlds. If there’s an art fair, you can hang a Marilyn Minter painting and photograph beside each other. It’s the same audience.”

Photography was long seen as the stepchild of modern and contemporary art, says Kennel, which she posits may have made the field less competitive and more open to women early on.

Yet even for photographers like Abbott and Cunningham, who were successful in their own day, the prices “for female photographers have been historically lower than those of their male counterparts,” says Davi Weston, owner of the Weston Gallery, in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, where she shows both artists.

In recent years, and particularly during the pandemic, the collectibility of photography as a whole has risen dramatically, according to Weston. “We have certainly seen an increase in sales of female photographers, both contemporary and early female photographers,” she says, hypothesizing that this trend might be influenced by the Me Too movement.

Weston notes recent record sales for works by Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin. “Much of their work explores gender roles and identity,” she says, “and we’ve seen a renewed focus on works with a strong voice, a protest.”