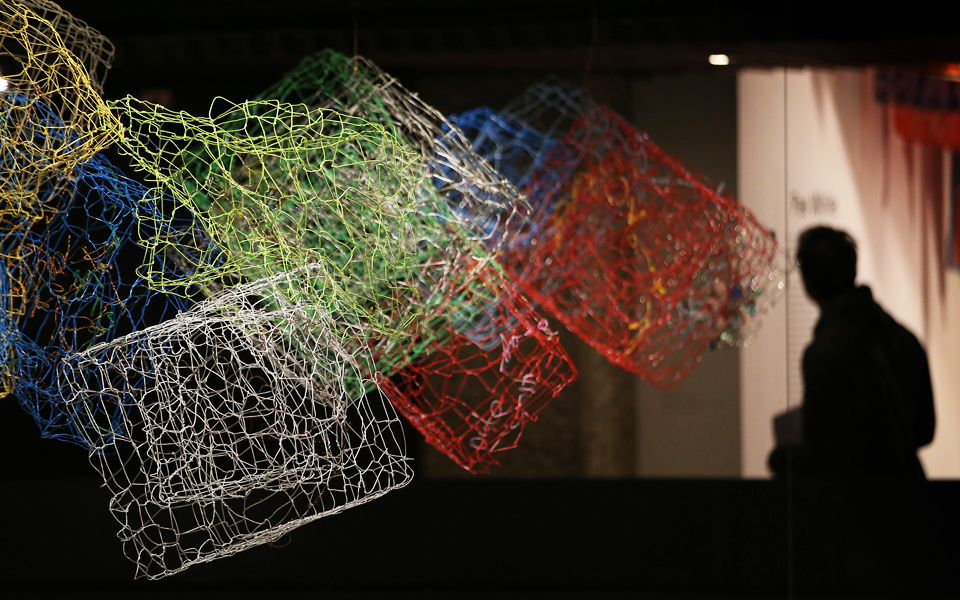

May 11, 2015On view through May 25 at London’s Barbican gallery, “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector” displays the eclectic personal collections of 14 artists along with original works (Andy Warhol’s are seen here). Top: Mexican tattoo artist Dr Lakra’s collection of vinyl record sleeves. All photos © Peter MacDiarmid/Getty Images

Years ago, I read a story in an art magazine that opened my eyes to the creative possibilities of collecting. The gist of it was that an object’s cost or importance didn’t really matter; what you needed to figure out was what obsessed you — be it seashells, jacknives or record albums — and build from there.

It’s that sort of primal acquisitive urge that often fuels artists’ collections. And that’s why, as anyone who spends much time in studios soon learns, looking at what obsesses an artist can deeply enrich your understanding of his or her work. We know that the angular features of the African sculptures Picasso collected often served as source material for some of his own stylistic experimentation. Similarly, Fred Tomaselli‘s collection of artificial fly-fishing lures, in all their decorative, eye-catching glory, seems to evoke the intricate assemblages of leaves, pills and collaged paper birds and flora that he seals beneath layers of resin in his work. Visit Lucas Samaras‘s home and studio, whose hallways and rooms are lined with self-portraits, as well as cubbyholes that display shoes, cooking utensils and art-making materials as if they were precious jewelry, and you see his surrealistic box constructions and manipulated Polaroids in a new light.

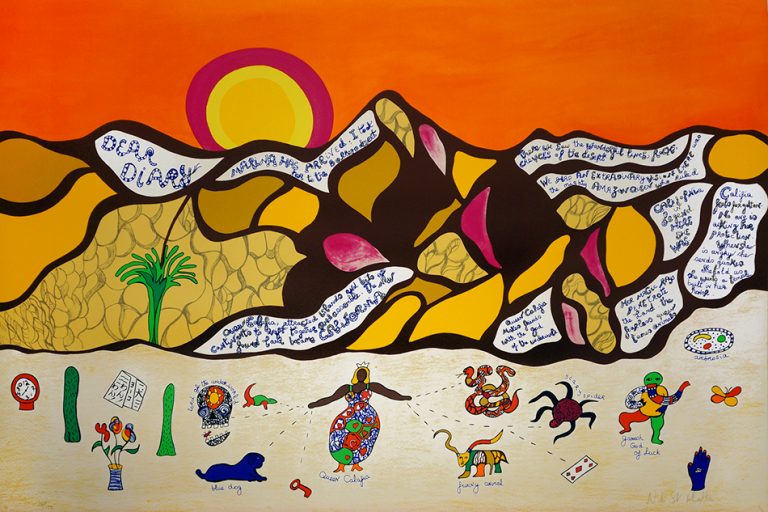

The show seeks to convey connections between artists’ collections and their creations, displaying, for example, this piece, Home Sweet Home II, 1960, by Nouveau Réalisme pioneer Arman, beside his personal collection of African masks and sculptures.

In addition, an artist’s collection often seems to teeter on the knife-edge between destruction and creation, because it frequently becomes raw material for new artworks. The sculptor Melvin Edwards, for example, works in a former foundry in New Jersey that’s overflowing with broken tools, rusty artillery shells and all manner of scrap metal — stuff he stockpiles because he can’t stop himself, but which sometimes ends up in his process-oriented assemblages (as seen in his retrospective, which just closed at the Nasher Sculpture Center, in Dallas). “In my world, anything might become something,” Edwards told me in 2012, when I profiled him for the New York Times. “And if you stand there too long, you might, too.”

That’s the sort of territory covered by “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector.” At London’s Barbican Gallery through May 25, with a reduced version traveling to the Sainsbury Centre, in Norwich, UK, on September 1, it’s a show so rich with intriguing ideas that it’s hard to stop thinking about it — even if you aren’t able to see the show in person. It’s filled with more than 5,000 objects drawn from the collections of 14 artist-collectors, including the Nouveau Réalisme pioneer Arman, represented here by museum-quality African masks and sculptures, and Britpop icon Damien Hirst, who contributed skulls and Victorian taxidermy. And the range is vast, veering from the most highfalutin Mughal gouaches and Kota reliquary figures to the humblest postcards and bric-a-brac. In more than a few cases (documented in the excellent Prestel catalog), this amazing range sometimes exists within the same collection, too.

De Waal began to collect seashells as a small child growing up in the United Kingdom.

The master ceramicist Edmund de Waal has loaned the shells, coins and other archeological fragments he collected as a boy, as well as the carved button-like Japanese sculptures known as netsuke that haunted the pages of his 2010 family memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes. From Andy Warhol‘s collection, there are cookie jars and mid-century toys, drawn from the holdings of a major pack rat who hoarded everything from junk mail to Art Deco furniture. Also in the show are objects owned by the Vietnamese-born conceptualist Danh Vo, who acquired the collection of another artist-collector, the East Village painter Martin Wong, after his death from AIDS-related illness in 1999. In 2013, Vo famously displayed a selection of Wong’s assorted artifacts and tchotchkes — including Asian scrolls, political campaign buttons and Buddhist, Disney and Negrobilia figurines — in his own solo exhibition, “I M U U R 2,” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which can be seen in its entirety here.

The curator, Lydia Yee, spent two years organizing the exhibition (and much longer conceiving it), partly because some of the artists were so wedded to living with their beloved objects that it required some persuasion to prise the work from their hands — even when said artist loved the idea, like the British Pop pioneer Peter Blake. Best known for creating the collaged album cover for the Beatles’ 1967 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Blake’s home and studio are overflowing with what Yee calls “British vernacular culture,” such as elephant figurines, enamel shop signs, 1950s cloth dolls by the doll-maker Norah Wellings and an installation of early-20th-century taxidermied animals acquired from the circus performer the Great Stromboli.

The curator, Lydia Yee, spent two years organizing the exhibition, partly because some of the artists were so wedded to living with their beloved objects that it required some persuasion to prise the work from their hands.

Over the course of four decades, American painter Martin Wong, together with his mother, amassed a trove of thousands of objects, including Buddhist figures, tourist souvenirs and Disney characters — a collection that reflects their shared taste for East Asian art and culture as well as Americana and kitsch.

Blake wasn’t nervous about loaning his doll collection, which he used to let his children play with. “I’m not precious about my collections,” he says. But some of the signs couldn’t be moved, he adds, because “to take that down would have destroyed the wall.” He was also loath to part with another taxidermy group that had once been part of Walter Potter’s Museum of Curiosities, a Victorian institution in Sussex that featured preserved animals arranged in whimsical anthropomorphic tableaux. “They’re set up as a little museum within my studio,” Blake says, “and to take anything away kind of unsettles it.”

That’s partly why Yee, formerly curator at the Barbican and now chief curator of the Whitechapel Gallery, took pains to organize the show as 14 separate installations, most of which suggest the way the work is normally displayed in the artist’s studio or home. “I didn’t want it to feel like a museological exhibition,” she says.

Warhol’s cookie jars line an enormous vitrine that suggests a kitchen cabinet. Indian miniatures from the collection of the British abstractionist Howard Hodgkin are hung in a space with green walls and Oriental rugs on the floor, as if to suggest a living room, while an installation dedicated to the German conceptualist Hanne Darboven precisely replicates a corner of her Gesamtkunstwerk-like home in a suburb of Hamburg, with a wooden angel and a model airplane suspended from the ceiling above an agglomeration of mannequins, signs, photographs and other knickknacks.

White stands among her collection of scarves designed by Vera Neumann, with which she’s created a site-specific installation.

The California mixed-media artist Pae White used her collection to create an installation that became a complex creative endeavor: an airy installation assembled from a tiny portion of her collection of scarves by mid-century designer Vera Neumann, which she’s been buying from garage sales and on eBay for 25 years.

Although White says she originally rationalized her collection, which now numbers more than 3,500 scarves, as a way to “assemble a design archive and reference library,” she has cannibalized it to make work in the past, and she did the same thing here. Early on, she says, she decided to “send the collection as raw material, and just see what happened when I got there.” She ended up filling the entire gallery with scarves, hung aloft by steel cables and tiny magnets, in rows of fluttering fabric that suggests pennants or flags.

White seems delighted with the finished work, but it was not accomplished without anguish, for she also signed a waiver that allowed the Barbican to display the fragile silks in full light, a decision that might lead to fading and fraying down the line. Yet while the lighting “compromised the texture,” she says, “I thought it was important. I had to sacrifice some in the interest of making the whole feel alive.”