September 25, 2022Before tech startups made San Francisco the epicenter of global digital disruption, it was a famously provincial town. Curiously, in terms of interior design, it still is. Sure, there are lots of great contemporary designers composing spare, luxe interiors for youthful tech titans, but for a place that is today so culturally diverse and future-oriented, their approach remains surprisingly Western and tradition-bound.

With the advent of Studio AHEAD you might say a systems upgrade is finally in the offing. Homan Rajai and Elena Dendiberia cofounded the design firm six years ago as a novel kind of practice, crafting interiors rooted as much in the freewheeling sensibilities of Northern California’s artists and makers as in the distinctive emotional and spatial narratives of their clients.

Why not, for instance, choose an unexpected palette of soft and vivid greens and moody steel grays for the new home of a young Korean-born client who loves the hues of earth and sky before, during and after a rainstorm? Or use a poetically patterned black-felt ottoman as a sculptural wall relief in a guest bedroom?

Why shouldn’t the Spartan yet multifunctional fittings of a traditional ryokan serve as a model for converting a design aficionado’s former office headquarters into a creative community project space — but with endlessly reconfigurable artisan-made modular metal furnishings and linen draperies substituting for the tatami mats and futons?

The designers call this process of syncretizing diverse elements and influences a new “Silk Road,” a term that also speaks to their origins.

Rajai is a child of the Iranian diaspora. He grew up in what he describes as “a nice, normal suburb” in the Bay Area, where he struggled to make sense of the incongruity between his heritage and his surroundings. Directionless in college, he majored in landscape architecture only because it combined nature and design, two lifelong loves.

That led to a seminal year in Kenya developing a way to supply fresh produce to a leadership-training school for disadvantaged girls in a community where drought and the overuse of pesticides had damaged the soil. His solution was a small “food forest,” a type of garden that has local roots and that he cultivated with the help of a permaculture specialist working only a few miles away.

The process demonstrated to Rajai how a designer’s willingness to research, collaborate and reimagine can change people’s lives and worlds. “I became committed to the importance of the three Es,” he says, “which you don’t talk a lot about in interior design: Economy, Environment and Equity.”

His commitment was strengthened several years later, when on another extended sojourn, this time in Mexico, he took a deep dive into the country’s folk culture and craft with a leading local designer/entrepreneur and saw how these traditions might be brought into a present-day culture.

Dendiberia was born and raised in Samara, a Russian port city on the Volga that was for centuries the nexus between Russia and the East. Laser focused on her career from early on, she holds graduate degrees in art and architecture and has exhibited her paintings internationally.

When in college, she spent time in San Francisco as an English-language exchange student and dated a young man whose parents hailed from another cosmopolitan port, Odessa, in Ukraine. She went back to Russia but eventually returned to the States to marry him. She got to know Rajai when they both were in the employ of a local interior design firm, which they credit for motivating them to go their own way.

Before they set out on their own, the pair designed an extravagantly expensive business card on heavy stock, embossed in silver with a cipher-like logo, at once ancient and futuristic. “We were super-serious about it,” says Dendiberia. Laughing, Rajai adds, “It was the only product we had. We had no portfolio!”

To test their ability to cocreate an actual space, they began developing a scheme for a fantasy mescal bar — think esoteric rituals and vegetal tastes — in an actual Chinatown basement. But they hadn’t gotten far when they landed their first clients: A 30ish husband and wife expecting their first child. The couple had recently moved into a sprawling apartment with jaw-dropping bay views.

Impressed with Rajai’s assessment of the space — and, no doubt, by his business card — they hired the firm to design the nursery. Before long, Studio AHEAD had transformed the entire apartment, commissioning bespoke furnishings and art, creating an environment that was a highly personal, eclectic mix of urbane and rustic, reflective of the couple’s actual lives, interests and tastes. So pleased were the couple that when they recently decided to move to the suburbs, they engaged the firm to house hunt with them and propose potential architects for the renovation. “They’ve become our patrons,” says Rajai with unabashed pride.

Encouraging clients to be “patrons” of artists and makers, rather than mere “collectors,” is very important to the designers. “We want them to have an appreciation of the craftspeople, their lifestyles and the process. It’s a more holistic approach,” says Dendiberia. “Rather than just having a product show up at their door,” interjects Rajai. “Humans interacting and engaging is what makes the work interesting.”

A recent example involved a frequent Studio AHEAD collaborator, the Inverness-based woodworker Ido Yoshimoto, whose father was the studio assistant of the chainsaw-wielding JB Blunk, a pioneer of California craft and the 1960s back-to-the-land movement. When Yoshimoto was set to install a monumental redwood portal commissioned by the studio for a Berkeley residence, the designers arranged for him, his wife and their six-month-old child to move in with the clients during the process. The clients were thrilled to feed and care for the family, no doubt recognizing that if Yoshimoto lived in Japan, he might well be deemed “a national living treasure.”

To make these kinds of human-aesthetic connections for a larger audience, Studio AHEAD publishes California: A Journal, a blog profiling past and contemporary makers who have contributed to the Golden State’s mighty cultural legacy. A reader is equally likely to chance upon a story about an obscure but brilliant mid-century designer like Jack Hillmer as an interview with the sculptor/farmer Jesse Schlesinger, who is another artist that the studio enjoys bringing on projects.

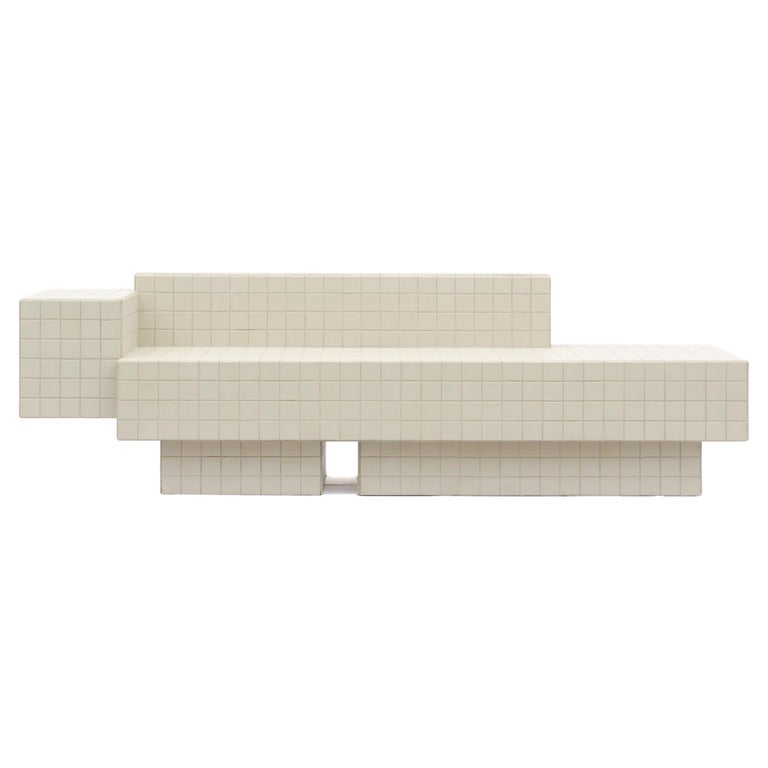

The designers’ shared passion for place also informs their recently introduced in-house production lines, Sheep and Russian River, which are offered on 1stDibs. The pieces, which include a bed, headboard, lounge chair, dining chair, stool and pillow — are as much about landforms as furnishings, although the designers also say they were inspired by Faye Toogood’s adventures in shape and form and Isamu Noguchi’s elemental monoliths.

Typical of the pair’s gentle subversions is their choice to cover their upholstered pieces not in fine leather or sumptuous velvet but in wool felt. The humble cloth has deep associations for them both. As a child, Dendiberia used to wear felt boots in the winter, and the material was intrinsic to the culture of the nomadic shepherds from whom Rajai descended. The studio sources its felt from JG SWITZER, a Sonoma-based artisan who works with wool from local merino sheep. Rajai notes that SWITZER’s thriving workshop helps sustain the small farmers who raise these heritage ovines.

And so, in this subtle, almost imperceptible way, rather like a cipher, Studio AHEAD integrates the three E’s: — Economy, Environment and Equity — into its visionary interior design.