November 22, 2020They became friends around 1976, when he was an off-Broadway set designer (and aspiring painter) and she was an up-and-coming actress. Two years later, Diane Keaton won an Oscar for Annie Hall. “Her fame ballooned, and I thought, ‘That’s the end of that friendship,’ ” remembers Stephen Shadley. “Who would have thunk that we would still be best friends more than forty years later?”

Early in the friendship, Keaton persuaded Shadley, who was born in St. Louis and grew up in Southern California, to help her update the interiors of a mid-century house in a small town north of New York City. The result — with bold, sculptural furniture positioned against bright white walls — was published widely, and a design star was born.

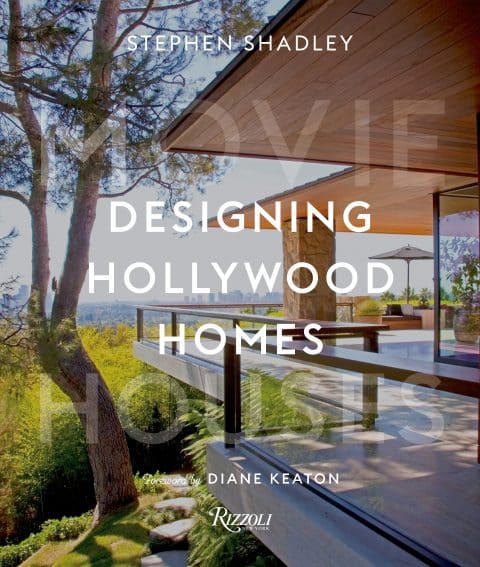

Since then, Shadley has helped Keaton renovate nearly a dozen properties, five of which are chronicled in his new book, Designing Hollywood Homes: Movie Houses (Rizzoli). Written with journalist Patrick Pacheco, the volume also covers Shadley’s collaborations with Jennifer Aniston, Woody Allen and the producing juggernaut Ryan Murphy, among others.

For Shadley, working with Hollywood stars is, honestly, a dream come true. “I was lucky to get into this niche,” he says in a phone interview. “Movie people tend to live out stories that are really interesting. It’s always an adventure.”

They also tend to know what they want. And that’s okay with Shadley, who says, “I’ve never tried to impose a look.” He became an expert in Spanish Colonial Revival as Keaton started buying one house after another in that style, which, with its white walls and lack of ornament, felt to him almost like a strain of modernism. Among them was a home in Bel Air that once belonged to the director Peter Bogdanovich. “Diane loved its shape and the feeling of safety and calm that its interior courtyard gave it,” Shadley recalls.

That it had been allowed to deteriorate badly wasn’t a problem for Keaton. “She even loved just how much work the renovation was going to take,” he writes in the book. Shadley created a new bedroom suite for Keaton and designed a living room that, thanks to its Monterey furniture and brightly hued Western paintings, evoked the waiting room of a California railroad station. That, he writes, was an homage of sorts to transience: “the nomadic life of an actor . . . the inevitable fact that as much as she loved this house, she would move on from it at some point.”

And she did. Keaton’s next house, in Beverly Hills, was also Spanish Colonial Revival. This one was built around a two-story courtyard with a gurgling fountain, which, Shadley says, “gave the house a theatrical flair.”

Surrounding the courtyard were loggias that he describes in the book as “a symphony of dark beams, white stucco walls, arched doorways, brick floors and black iron grilles.” They provided, he writes eloquently, “the reassurance that comes from repeated elements.” Inside, Keaton and Shadley created five new fireplaces based on a sketch he drew of an arched brick opening surrounded by white stucco.

In 2010, Keaton sold the house to Murphy, who kept it essentially the way it was as his career skyrocketed and he and his husband, David Miller, had their first two children. Then, around 2015, the couple decided to buy a larger Spanish-style house on a hillside in Pacific Palisades. Naturally, Murphy called Shadley, whose handiwork he’d been living with happily for years.

Murphy told Shadley he had decided to make the new house “monastic.” Its materials, when it emerged from a renovation that took about four years, were limited to white stucco, dark oak, black stone, wrought iron and black-and-white tiles.

But Murphy’s idea of less was more. The place is so big that what looks like the living room is really just the foyer outside the living room. It’s so big that Shadley needed thousands of custom tiles with black-and-white geometric patterns to cover a semicircular outdoor stairway that Murphy calls, exaggerating only slightly, the amphitheater. It’s so big that the plaster horse-trough fountains out front required lap pool permits.

The house never feels overwhelming, however, because Shadley got the scale just right. He devised the large black lampshades that hang from the ceilings all over the house as a unifying element. In the kitchen, he created a granite island so minimalist it resembles a Donald Judd sculpture. “Ryan didn’t want anything to distract your eye when you came in,” says Shadley. And the fireplaces, based on the ones he designed for Keaton’s Beverly Hills house, were built to achieve a “regal, walk-in effect.” (Although Shadley did all the interior architecture and lighting, the furniture was chosen by Pam Shamshiri.)

Meanwhile, Aniston had bought a house in Beverly Hills and needed a designer. Her contractors recommended Shadley, whom they knew from two of the Keaton renovations. (“In all those years, I never had anything even close to an uncomfortable moment with the contractors,” says the easygoing Shadley.) Aniston welcomed the designer into her life, even throwing a dinner party to introduce him to her closest friends.

“Having just ended her first marriage, Jen was eager to turn the page,” he explains in the book, “and it was clear that a new chapter of independence was being written, in part, through a house she clearly loved” — one that she hoped would be “a sea of tranquility amidst the bustle of her life.”

Aniston and Shadley made a few big moves, like building a new terrazzo bridge to the front door and extending the house’s eaves, which are clad in coumarou (also called Brazilian teak). For the interiors, Shadley channeled the home’s ’60s spirit, installing trellised room dividers, shag carpeting and other reminders of the Rat Pack era. “I didn’t care if they were fashionable or not,” he writes.

Then Aniston and Shadley (and the paparazzi) went shopping together. On one of their first excursions, Aniston bought a German fruitwood and brass piano that eventually made the cover of Architectural Digest. What they couldn’t buy, they had made, including 24 copies of a 1960s walnut and black-linen dining chair that Shadley purchased on 1stDibs.

In 2011, Aniston bought a larger house, in Bel Air, and asked Shadley to do the interiors. “I found someone now more confident in her choices and sense of style,” he writes. “She knew how she wanted to live.” The house, the work of architects A. Quincy Jones and (later) Frederick Fisher, “was a little too cool and minimal for Jen’s taste,” so the first order of business was to introduce “materials with texture, substance and depth.”

The house is still modern — the living room has a wall that slides open into pockets at the touch of a button — but the furnishings are comfortable and mostly vintage: a Royère sofa with a pair of Adnet chairs and a Mies van der Rohe chaise in the living room, a quartet of Piet Hein stools at the Shadley-designed bar.

In Aniston’s bedroom, a polished-wood and plush-carpet platform bed designed by Shadley is flanked by a pair of monumental circa 1970 lamps by Philip and Kelvin LaVerne, among the few items Aniston brought from the previous house. (The family that bought that house wanted Shadley’s interiors, undiluted.)

While Shadley was working with Aniston, Keaton had found him another client, her old friend Woody Allen. Keaton told him, “He’ll be really easy — he won’t be like me.” And Allen was a “complete gentleman,” says Shadley, who helped the director and his wife, Soon-Yi Previn, renovate a townhouse on New York’s Upper East Side.

The couple were moving from a larger house, which meant putting much of their furniture in storage. “I spent a lot of time in the ‘editing room’ with Woody,” Shadley writes. They ended up with a house full of Americana: samplers, hooked rugs, brass, wicker, pewter, “stuff he’s carried with him his entire life,” the designer says.

For years, Shadley has lived and worked in a loft in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. When COVID-19 hit, he moved up to his weekend house in the Catskills, which he built on the foundation of a 1913 lodge created, fittingly, by a production designer for Cecil B. DeMille. As we speak, woodpeckers tap outside his windows. “They’re turning the cedar shingles into swiss cheese,” he says.

At the start of the pandemic, he had three large projects, and all three have moved forward. Two are new houses, on Nantucket and in Aspen; the third is the renovation of a house in San Diego by Richard Requa, that city’s leading exponent of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture in the first half of the 20th century. (The owners of that house called Shadley after seeing Keaton’s 2007 book, California Romantica, which was recently reissued by Rizzoli.)

Shadley still talks to Keaton twice a week. A few years ago, she decided to build a house based on images she had been gathering on Pinterest. “She wanted to do it on her own, but about halfway through, she called me in as a kind of project manager,” says Shadley. When the job was complete, Keaton wrote a book about it: The House That Pinterest Built (2017). It could have been subtitled With Help from Stephen Shadley!