June 8, 2015The L.A. gallery Seomi International focuses on contemporary Korean design, including work in wood by Bahk Jong Sun, Choi Byung Hoon’s Afterimage 09-313 table and Capote, 2014, by one of the gallery’s non-Korean artists, Joana Vasconcelos. Top: The gallery enjoys a rarefied setting in a mid-century house designed by Pierre Koenig.

What would you do with a world-famous Case Study house? In 2006, when P.J. Park, the founder of the Seoul-based art gallery and consultancy Seomi International, paid Wright auction house some $3.5 million for architect Pierre Koenig’s 1958-59 Bailey residence in Laurel Canyon (also known as Case Study House 21), the answer seemed obvious. Park treated it like a work of art, furnishing it with period-correct French, Scandinavian and American vintage designs from his personal collection. “It was a very enjoyable environment,” he says. Yet he felt that it could become more. “Since it was just a static museum reflecting the 1950s, it was a complete disservice to the landmark.”

In 2012, along with his business partner, Jacob Koo, Park decided to turn the house into a stateside outpost of Seomi, having it function as a by-appointment gallery focused on contemporary Korean design. The initial goal, which still informs the mission today, was to bridge the gap “between eras of art, design and architecture and blur the lines between each school a little further,” says Park. Still primarily based in Seoul, Park drafted Linus Adolfsson, who had been working with Koo, as managing director of Seomi International.

Adolfsson, 27, has reimagined Case Study House 21 as an interactive gallery environment to showcase Seomi’s artists. (It remains by-appointment on the weekends and is open to drop-ins during the week.) The current show, “Living In Art II: Connect,” on display through July 15, includes pieces by six of Seomi’s artist-designers, along with work by a few of the non-Koreans the gallery represents, including Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos, who is known for her crochet-covered animal sculptures.

In 1959, famed architectural photographer Julius Shulman shot what is now Seomi International’s home in Case Study House #21, Los Angeles, CA, which is available from Yancey Richardson Gallery, in New York.

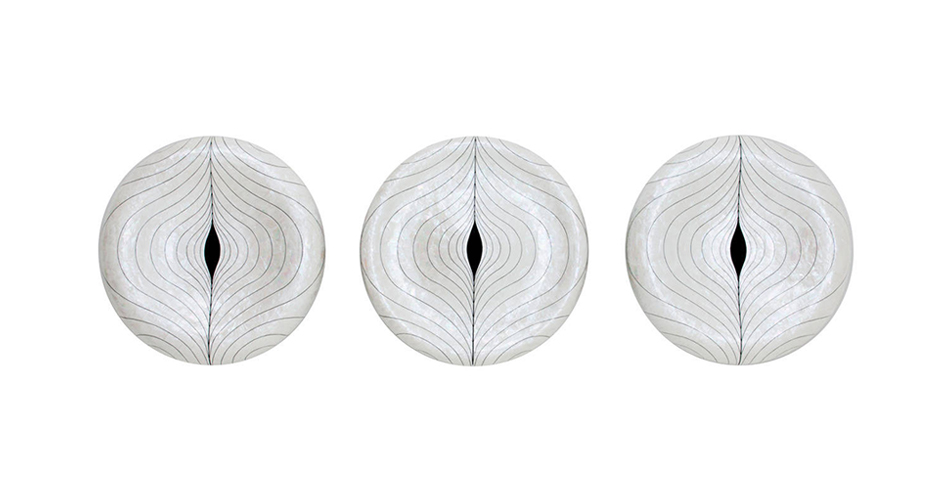

In the living room, visitors can perch on an undulating wooden slat bench by Bae Se Hwa and admire an exquisite marble table by Choi Byung Hoon, a master sculptor of stone and wood, or a lean De Stijl–esque chair by Bahk Jong Sun. In an adjoining bedroom, there is a Kim Sang Hoon settee made from stacked steel sheets, and a curvaceous black-lacquer wall cabinet painstakingly inlaid with mother-of-pearl by the artist Kang Myung Sun. Looking through Pierre Koenig’s innovative glass walls, one can see Lee Hun Chung’s monumental concrete and richly colored ceramic tables, seats and sculptures decorating the grounds.

“Art fairs are like one-night stands: You seldom get the opportunity to start a collaborative process with collectors,” Adolfsson says. (Indeed, Seomi has had a robust presence on the fair circuit over the past few years, exhibiting at Design Miami, PAD London, FOG Art+Design and the Salon Art + Design Fair, among others, and it has participated in exhibitions on contemporary Korean design at New York galleries R & Company and Edward Tyler Nahem.) “This house emphasizes the treasure-hunting and pleasure-seeking that collecting encompasses,” Adolfsson goes on to explain. “The space is a work of art unto itself and promotes our idea of living with great pieces, giving people an idea of how they can be placed in a home, indoors or out.”

After a recent tour of the current exhibition, Adolfsson sat down with Introspective‘s David A. Keeps to discuss the historic house, the exciting state of Korean design and the very particular gifts of Seomi’s stable of artists.

What is the current state of art in Korea?

Korea has a long tradition of handwork, but because of the war and its lingering after-effects, there was no time to focus on art and craft until the 1990s. Now, Korea is one of the most interesting places in the art world. People are not living in the same way that their forefathers did, and there is an ingrained appreciation for contemporary art and design, which comes from the explosive economic growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Korean art mirrors new trends in Asia, Europe and the U.S. and also reflects its past traditions. Artists are not afraid to be influenced because they can stay true to centuries of handcraft. At Seomi, we do like intellectual art, but we are not shying away from pure decoration for beauty’s sake.

Tables and chairs painstakingly inlaid with mother-of-pearl from Kang Myung Sun’s 2013 “From the Glitter” series occupy the house’s kitchen.

How would you define the Korean aesthetic?

There is pureness, simplicity and boldness. Danish design is more sublime and in the background. Korean work speaks loudly and commands the place and your attention, whether it’s in a room or a backyard. At the same time, it’s very Zen and meditational, and there is a close connection to nature.

What makes certain examples of Korean design more desirable than others?

For us, the qualities we look for are a connection to history and the talent for handcrafts. We believe in artists who have a complete vision and know how to fulfill it. It can be a long process. One of our youngest artists, Bae Se Hwa, creates sculptural furniture from steam-bent walnut with no nails, a technique that has been used for thousands of years and now is shown in a contemporary language. It requires great skill and time; he only makes two or three pieces a year. Lee Hun Chung’s work is inspired by Joseon Dynasty pottery, but the pieces are so large they each need to be in a wood-burning kiln for seven days and only 10 to 15 percent survive the process. Kang Myung Sun works in hand-carved wood with applied mother-of-pearl and is the first to do it on curved surfaces. Working in wood can be agony: it’s you against the wood every millimeter, and the way Bahk Jong Sun, who does architectural seats in wood, finishes his pieces is almost sickening.

What is the most unusual object you have handled?

The artist closest to my heart is Lee Hun Chung. One piece of his, which I placed with a collector who lives in Howard Hughes’s old house in Hancock Park, was a seven-foot long ceramic sofa that almost looked like a Jackson Pollock painting. It took eight people to move it down a crazy little staircase to sit by a pool.

“Art should not only be something you enjoy visually and intellectually, but also something you interact with,” says Seomi managing director, Linus Adolfsson.

Do you have to take special precautions living with such artwork?

With the ceramic and marble pieces, you can go crazy: Use it indoors or outdoors from Moscow to Palm Springs. The mother-of-pearl tables and chairs are very durable and can even be used in corporate settings. The wood pieces earn their patina; in the sun, they might become bleached, but that’s not necessarily bad. The whole idea is to use these pieces and make memories. We’re talking about starting a “Please Touch the Art” campaign.

What advice do you have for collectors?

Art should not only be something you enjoy visually and intellectually, but also something you interact with. We believe in living with something on a daily basis, which brings you back to a time when handcraft was respected. Because we live in a fast, technical, mass-produced world, we are drawn to the things we can touch.

How can aspiring collectors learn more about Korean art?

In Seoul, the Korean Furniture Museum encapsulates everything, and you can see how a lot of contemporary design is based in tradition. And there are fantastic private museums like the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, which has both contemporary pieces as well as ceramic and mother-of-pearl pieces from 1300 to 1800. If you can’t go to Korea, try the Asian Art Museum, in San Francisco, and the Met, in New York.

Visit Seomi International on 1stdibs