“I must have been Italian in a former life,” says bicoastal film producer, art historian and prolific collector Ronnie Sassoon. “My love of most anything Italian, especially from the nineteen sixties and seventies, goes beyond mere desire. It is more like a visceral passion and an intuitive kind of familiarity.”

This passion is on full display in Selection: Art, Architecture and Design from the Collection of Ronnie Sassoon (August Editions). The stunning new book — complete with a corrugated cardboard cover that recalls the Arte Povera works on her walls — showcases an impressive collection of late-mid-century, predominantly Italian art, furniture, light fixtures, jewelry and decorative objects.

Sassoon’s homes are themselves pieces of design history. She and her late husband, salon magnate Vidal Sassoon, bought several masterpieces of modernist architecture in Los Angeles, including two by Richard Neutra.

She now shares one of the Neutra structures — the Levit House, in Beverly Hills — with her current husband, James Crump, a filmmaker, art historian and museum curator. The couple also has an industrial-chic loft in Manhattan’s Soho and a stone and glass Marcel Breuer house in the woods of northwestern Connecticut.

In all three, Sassoon has created a harmonious marriage of natural and manufactured materials perfectly in tune with each other. Yet many of the characteristics of her homes’ various elements were considered radical in their time — the simple natural materials used by 1960s movements like Arte Povera to subvert conventional expectations of art, the curvilinear shapes of 1970s-era de Sede and Angelo Mangiarotti furniture, the open floor plans of modernist houses. These express a transgressive ethos that Sassoon appreciates.

“I am drawn,” she says, “to the postwar avant-garde’s absolute commitment to openness, freedom and defying the status quo. I like being different, I am somebody who doesn’t do what other people do. I want to create my own thing, my own style.”

Introspective sat down with Sassoon to learn about her distinctive style, displayed in everything from her wardrobe to her gourmet cooking, which imbues both her new book and how she lives her life.

How important is historical context to your interest in the objects you collect?

I am deeply committed to Arte Povera and Group Zero and the furnishings from that period, which portray the same sense of radicality and provocation that profoundly changed the aesthetic discourse in the second half of the twentieth century.

For instance, a biomorphically shaped dining table — like my Charlotte Perriand Forme Libre table in the Neutra house — eliminates any kind of hierarchy. There’s no head of the table, and you sit on stools instead of traditional chairs, because having to sit straight up in a stool keeps your mind agile, which makes for more-scintillating conversation.

How do you find your furniture pieces, and what do you look for?

I usually know what I am looking for, so it’s about the hunt. I see a room in a certain way, and then I develop a wish list for it. Knowledge and education are so important. I collect books and ephemera of every artist I am interested in. And I go through vintage design volumes from the 1960s and 1970s to find unusual pieces in unique rooms.

Then, I have to figure out who designed them before I start the search. This takes awhile, even years, as you can’t simply go into a store and buy them. The virtual hunt is the most expansive, and 1stDibs is usually my first stop.

In general, I look for pieces that are not what one would expect. I enjoy having a piece of furniture where people say, “Oh wow, I would never sit in that,” and then they sit and are surprised by how comfortable it is.

For instance, my Marzio Cecchi spiky beanbag looks menacing but is actually super comfortable. Also, my Verner Panton Flying chair appears awkward but is actually the most wonderful lounging chair.

You are also interested in Japanese influences. How does your Alexandre Noll cabinet in your Beverly Hills home illustrate the concept of wabi-sabi?

The Noll cabinet, carved out of one piece of wood, is one of my favorite pieces. It has a strength and energy that I find imposing and exciting. It’s a perfect example of wabi-sabi, with all its cracks and crevices and primitive imperfections. Wabi-sabi welcomes that patina, and cracks are part of the natural aging process of everything.

The cabinet’s amazing presence also references the Arte Povera philosophy of putting one’s faith in nature instead of following the status quo. Arte Povera was a reaction against the mandates handed down by the postwar Italian government, which encouraged baroque styles in design because those would portray Italy as impressive and important.

Artists began taking a radical stance and attacking these values of established institutions of government, industry and culture that they believed to be capitalistic.

Minimalist or modernist homes can sometimes feel cold. Yours don’t. How do you accomplish that?

The lighting and balance of materials are key to creating a warm environment, particularly a minimal one. I rely on nature to soften anything hard-edged. Natural materials and colors are also integral in infusing soul and warmth into a home.

For instance, I placed the soft beige leather de Sede Non-Stop sofa and the small wooden Gianfranco Frattini nesting tables in the Breuer house to add textural softness in contrast to the waxed-brick floor.

Soft shapes also help to add warmth. The sofa is called the Non-Stop because you can add or subtract sections and make it into any shape, like the soft, snaky curve I did, or it can be absolutely straight. Each individual section is connected to the next by a huge zipper. In the nineteen seventies, you could buy as many sections as you wanted.

At the time, people customized them. I have never found another one with this unique coloration, so mine remains as I originally bought it.

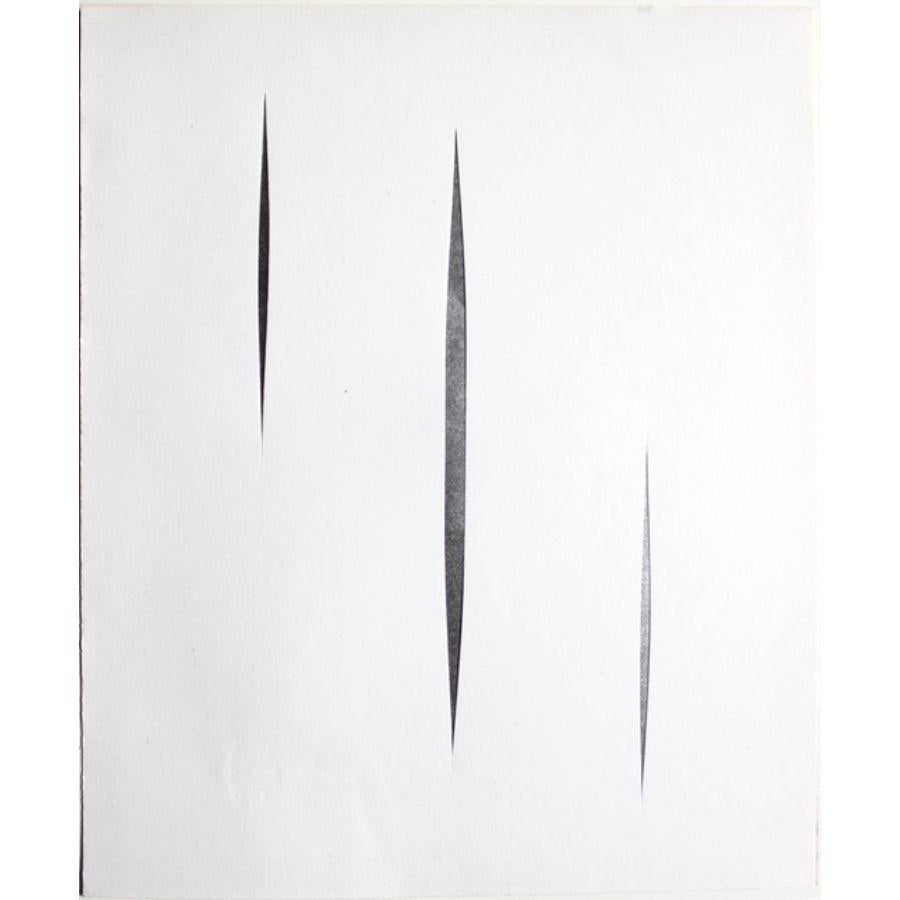

Your interest in Italian design extends to fine art. Several paintings and sculptures by Arte Povera master Lucio Fontana appear throughout the book, many titled Concetto Spaziale, or Spatial Concept. Can you explain what that term means?

Concetto Spaziale is a title Fontana almost always used in his work. In his Manifesto Blanco [White Manifesto] of 1946, he announced his intention to make “spatialist” art and try to achieve an expression of a fourth dimension that transcends space and time.

He looked to science and technology to assist him in achieving this goal and, in the process, held a firm belief in erasing traditional boundaries between architecture, painting and sculpture.

Fontana favored the infinite, inconceivable, chaotic forms of nothingness. He ultimately found that what was more interesting than the canvas’s surface was what went beyond it — a void that emphasizes the uncertain qualities of the future. Which is something we can all relate to in these uncertain times.

I like that Arte Povera sought to remove seemingly oppressive societal structures in an effort to achieve individuality and liberty. I also find pleasure in its radical political connotations, as well as its poetic ones.