March 30, 2025Celeste Robbins is something of a rare bird. She first made her name as an architect, masterfully crafting modernist houses that melded gracefully with their natural surroundings. Now, she is gaining notice as a decorator, thanks to the highly personal and sophisticated interiors she’s begun creating for the homes crafted by her firm, Robbins ARCHITECTURE, based in Winnetka, Illinois, just outside Chicago.

When describing how she combines materials and forms in her holistic creations, she uses an avian analogy, likening the process to a bird interweaving “grass and twig in the unique expression of its nest.”

Another essential element in this artful nest making is the input of the client. Robbins says it’s because she’s “a people pleaser,” but, in fact, she understands that shaping a home singularly suited to an individual, a couple or a family entails addressing their desires, including their last-minute requests. To her, such late-stage revisions add richness to the design.

“They don’t allow you to fall back on a diagram,” she says. “You have to give the design a little complexity, and that’s how it becomes so livable for them.”

Which is why when satisfied clients give tours of their completed houses and point out a detail, declaring, “This was my idea!” Robbins confesses to a sense of pride — a highly unusual response from an architect, a tribe famous for their egos.

But then, much about Robbins’s career has been unusual. To hear her tell it, establishing a design firm like hers once seemed as unlikely to her as it now seems foreordained to everyone else.

Robbins grew up outside Akron, Ohio, in the 1970s, a time when women were only beginning to pursue careers beyond the realms of teaching and nursing. Although she was a gifted artist, her aptitude for math and science convinced her father that she should follow in his footsteps and become an engineer.

Soon after entering Ohio State, however, a chance visit to an architect’s office, where she glimpsed his drawings and models, convinced her to change course, and she transferred to the architecture school at Cornell.

After graduating, in the mid-1980s, she took jobs at architecture studios that specialized in designing schools, ending up at a large firm in Chicago, where she had moved after getting married.

While there, she began moonlighting, making architectural drawings at night for Berta Shapiro, who had just set up shop as an interior designer. (Shapiro would soon become one of Chicago’s doyennes of design.) The two bonded.

“We leaned on each other a lot,” Robbins recalls. And in the process, she says, she began learning “how a home lives — things like where you want to sit when you walk into a room and what you want to see.” These were aspects of residential architectural design that Cornell hadn’t taught her.

After giving birth to her first child, Robbins decided to leave the big firm. “I wasn’t going to be pumping milk in the office bathroom,” she quips. Instead, she began taking on small projects — many thanks to recommendations from Shapiro — and working at night in her basement, so that she could spend the day with her son.

Eventually, in 2003, after the birth of her daughter and about eight years of what she describes as “a messy working-mother situation,” she received a major commission for a 9,000-square-foot family vacation home on a spectacular site in Jackson, Wyoming, at the foot of the Grand Tetons. She would work in tandem with Shapiro who was to design the interiors.

This would have been a choice assignment even for a starchitect. It was all the more extraordinary for Robbins, because she had never designed a house from the ground up. Yet, despite her lack of experience, the ranch-inspired contemporary house she produced was virtuosic and was soon featured in Architectural Digest, leading to major residential commissions across the country.

She has now completed another project for the couple who launched her career with that Wyoming house, acting as both architect and interior designer to create a charming family retreat for them on Lake Michigan.”

The beachfront property is small, but remarkable thanks to its location on a large hill that slopes up before dropping a precipitous 20 feet to the water. In her architectural design, Robbins made clever use of this topography, although it’s not apparent on first sight.

The couple wanted a house that wouldn’t draw attention to itself, so she rendered it as a cottage with a pitched roof and cedar-shingle siding, a vernacular common to the area. Yet despite its traditional exterior, the house possesses a modernist soul. The ground floor has a simple open plan with a windowed back wall, which makes the space feel to those in it as if it were floating on the water.

The pitched roof is equally deceptive, since the ceilings inside are flat, designed to imbue the rooms with “a crisp, modern edge.” So, too, is the house’s snug appearance, as it measures a generous 7,500 square feet.

It’s quite efficiently planned, too, with a central staircase in the rear, four ample bedrooms with en suite baths on the second floor and, on the lower level, which is tucked into the hillside, a bunk room, media and play spaces and a garage. There’s not a single hallway anywhere, because the wife doesn’t like them.

What she does like, as does her husband, is mid-century modern, Scandinavian and Japanese design. So, Robbins fashioned interiors that are richly inflected with these aesthetics.

To furnish the great room, for example, she selected pieces by two masters of mid-century design: a pair of lounge chairs by Hans Wegner and a Tank chair by Alvar Aalto. These pieces don’t stand out as overtly iconic, however, because Robbins mixed them in with other furniture custom designed for the project. And she upholstered them in the same soft palette — one that speaks of land, water and sky — that she used for materials throughout the interior.

Neither does the trio of rush chairs by Charlotte Perriand, which supply seating around the dining banquette, or the Isamu Noguchi Akari globe pendant above it, because Robbins always strives to avoid ostentation.

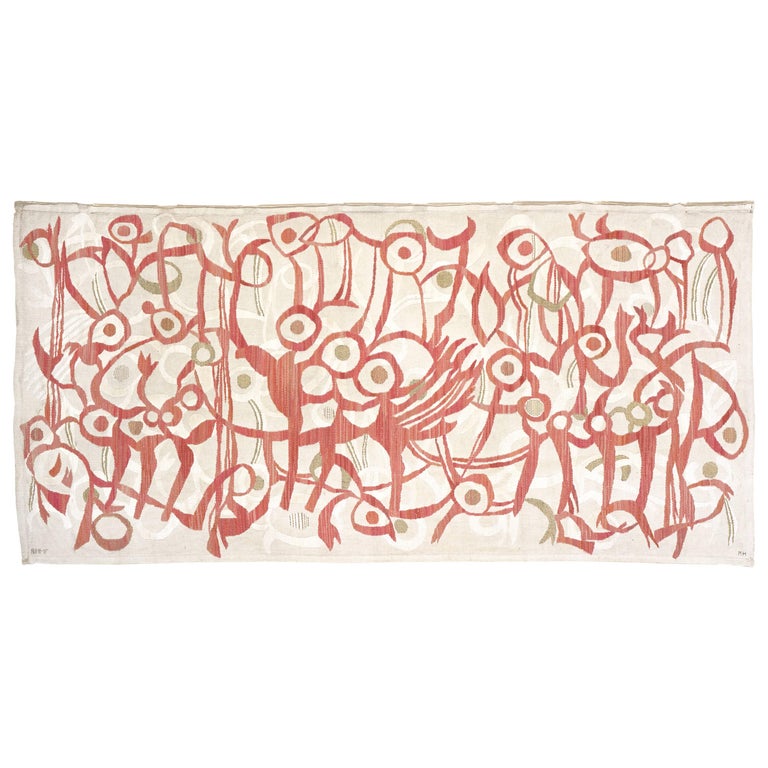

Instead, with the additional layering of intriguing textiles in subtle patterns, well-placed nature-inspired modern and contemporary art from the couple’s own well-chosen collection and outdoor views at every turn, this home is expressive not of a style, or a look, but of one particular family’s taste and way of living in a very special place. Robbins wouldn’t have it any other way.