November 28, 2016Rene Gonzalez opened his Miami architecture firm in 1997, and today he is advising city officials on how to deal with rising sea levels, while also building elevated structures that can endure hurricanes (photo by Stephan Goettlicher). Top: Gonzalez designed the Alchemist boutique as a glass-walled box nestled on the fifth floor of a Herzog & de Meuron–designed parking structure in Miami Beach. Photo by Michael Stavaridis

If one were to scramble to find a bright side to the rising sea levels in South Florida, it’s the creative architecture and design emerging in response to the changing environment. While Miami Beach has been busy installing industrial seawater pumps and raising major thoroughfares around the city, architect Rene Gonzalez is working to revolutionize the way buildings deal with seasonal high tides and storm surges. For him, it’s a matter of working with the salty swells rather than fighting them, adapting his tropical modernist style to handle whatever the sea might send his way. “I grew up in Fort Lauderdale, and it was a very relaxed, tropical place,” says Gonzalez. “We went to the beach a lot. We lived on a canal, so it was very connected with the water. My appreciation of environmental issues and, specifically, Biscayne Bay and Miami, have a lot to do with that. It’s in my DNA, if you will.”

Deeply connected to the Miami area, where he started his practice 19 years ago, Gonzalez has designed numerous gems around the city. (Art world insiders might be familiar with his rehabilitation of the 1936 warehouse that’s now home to the CIFO/Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation in Wynwood or the numerous projects he’s done for the Wolfsonian Museum, on whose board he has served.) Lately, he’s been advising Miami officials on how to rewrite the building code to address the rising sea levels, but he is also leading by example.

While working on commercial and residential projects, including his first restaurant (Plant Food + Wine at the Sacred Space, in Wynwood) and Glass, an ethereal 18-floor residential tower on the southern tip of South Beach, the architect has created four sophisticated “elevated” houses — three in the region and one in New York’s Hamptons. A far cry from the typical beachside box-on-stilts, each is tailored to its surroundings. What they all share is a first floor elevated above an open-air ground-floor space designed for either outdoor living or parking. They also all have landscapes generously planted with saltwater-tolerant flora that can survive an ocean swell. “They’re designed so if a hurricane blows in, the material can survive and come back almost immediately,” the architect says of the structures. A fifth elevated house — for himself — on Belle Isle, one of the Venetian Islands in Miami’s turquoise Biscayne Bay, is in the planning stages.

In the living room of this Allison Island townhouse, double-height windows maximize the natural light, which is softened by sheer curtains. Photo by Michael Stavaridis

The houses represent a singular mix of wide-ranging influences, from International Style modernism to Cuban vernacular architecture (Gonzalez directed the Center for Cuban Architecture at Florida International University for some years). Cantilevered floors, pilotis and gardens running beneath houses combine with perforated walls that allow sunlight and cool breezes to pass through. Thoughtfully placed courtyards and porches encourage indoor-outdoor living, a priority for Gonzalez. Views are key, and if there aren’t any, Gonzalez orients the gaze upward toward the sky. Concrete walls seem to float; glass partitions seem to open up the space while demarcating it.

It’s a creative use of materials, which Gonzalez partly credits to the time he spent living in Los Angeles. Shortly after he finished his graduate work at UCLA, Richard Meier and Michael Palladino handpicked him to work with them on the Getty Center. “It was an exciting time in L.A., in the mid to late eighties, because a lot of architects in the Frank Gehry school were experimenting with materials and introducing work that was very experimental,” he recalls. “That was very formative for me.”

Gonzalez is quick to point out that creating adaptive houses, for him, is not just a matter of being green. “It’s almost irresponsible for architects to not take the issue of climate change into account, but I also have to admit my interest in working with the environment really comes from wanting the architecture to be connected to a place and to amplify its qualities.” Amplify is a term the soft-spoken, low-key architect uses often. There is nothing loud or exaggerated going on here, however. Rather, what Gonzalez hopes to do is enrich life by creating a more sensory, or viscerally amplified, perception of it. “It’s about materiality and color and the psychology of space in relation to the proportions, and how one can magnify the experience of using a building,” he explains. At the Icon, a stylish 12-unit residence in South Beach, he arranged interior “walls” of pivoting gray-mirror panels, or louvers, whose reflective surfaces change with the weather and time of day. It’s all about ambience, and Gonzalez is a master at creating it.

“It’s almost irresponsible for architects to not take the issue of climate change into account, but I also have to admit my interest in working with the environment really comes from wanting the architecture to be connected to a place and amplify its qualities,” Gonzalez says.

For his first restaurant project, Gonzalez designed Plant Food + Wine at the Sacred Space, in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood. Photo by Michael Stavaridis

So it’s not entirely surprising that Gonzalez’s current projects include a new wing for the Standard Miami, still in the planning and permitting phase. Located on Belle Isle, about a mile west of the South Beach fray, the hotel happens to be adjacent to the plot where Gonzalez is building his new home. His plan for a storm-friendly waterfront wood, glass and concrete structure has a breezily chic, modernist ethos that fits the Standard, which was built as a motor inn in the 1950s. Its mid-century modern bones were expanded when it became the Lido Spa in the ’60s. It was revamped around a decade ago by André Balazs, the tastemaker developer whose not-so-secret weapon has long been ambience. “They’ve looked forward to freshening up the property for some time,” says Gonzalez, who has designed three different types of suites, including elevated bungalows inspired by huts he saw in Cartagena. “It’s kind of the prefect place to do it, because the Standard in Miami has always been a very chill, bohemian hotel.” His vision also includes a new system of saltwater-loving mangrove trees and hanging gardens.

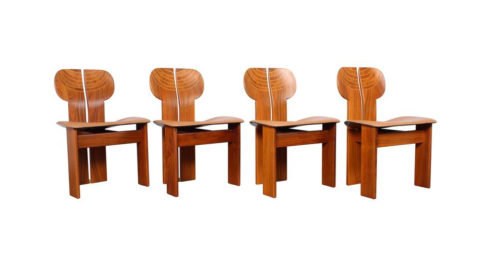

“I want to create a memorable experience in my projects,” says the architect, who is just as attentive to interior details as exterior ones. A big fan of vintage and contemporary design, he frequently seeks out “special” objects and collaborates with makers. “Using the work of artists or designers we love brings positive energy to the spaces. It’s not always clearly defined, but it can be felt. And it can really impact someone’s experience of space.” His interest in contemporary design has inspired him to launch a new curatorial platform during Art Basel Miami Beach: a gallery that will change locations with each exhibition. Opening November 30, RGA Rocket, as he’s named it, is starting by spotlighting the work of five designers. “The idea is that we are able to expand the practice and reach a broader audience,” says Gonzalez, noting that the shows will dovetail with his architectural interests. The first one explores materiality “and how objects can be spatial in nature.” For example, he explains, a colored glass table in the show by Eindhoven-trained Germans Ermičs functions as a table but also offers a more ephemeral sensorial experience, mimicking the sea and sky of Miami.

The pop-up project is not without connections to rising sea levels: Designer Mauricio del Valle is presenting cypress trunks that have become beautifully pitted and worn while submerged for a century in swampy areas of South Florida. What’s more, the show is located in one of Gonzalez’s recently finished elevated structures — the Prairie House on Miami Beach’s Prairie Avenue — which is not yet occupied. This might be your only chance to catch a glimpse of the future of architecture in an era of surging seas.

Rene Gonzalez’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs