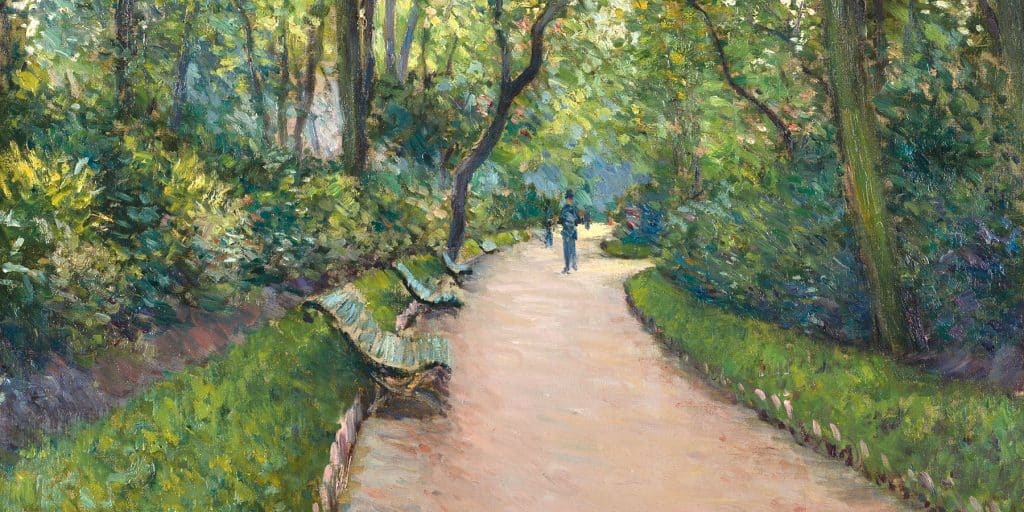

April 8, 2018On view at the Met through July 29, “Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” displays French works from the late 18th through the early 20th century, including photographer Eugène Atget’s Versailles — Cour du Parc, 1902. Top: The Parc Monceau, 1877, by Gustave Caillebotte. All photos courtesy of the Met

In France, the decades that followed the political revolution of 1789 saw something of a green revolution. By the early 19th century, the availability of exotic flora from abroad, along with advances in hybridization, triggered an explosion of interest in plants and flowers. The opening to the public of once-private royal gardens — like those at Versailles and Paris’s Tuileries and Luxembourg gardens — helped turn parks into places where people gathered to see and be seen, as well as to enjoy nature. Artists from Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot to Édouard Vuillard, including, famously, Claude Monet, painted many of the gardens, both private — their own and those of their friends — and public. The transformation of the French landscapes captured in their works is the subject of “Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence,” an illuminating and exceedingly pleasurable exhibition that runs through July 29 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition was put together by Susan Alyson Stein, the Met’s Engelhard curator of 19th-century European painting, with guest curator Colta Ives, curator emerita in the Department of Drawings and Prints, and Laura D. Corey, a research associate in the Department of European Paintings. It comprises 150 works by more than 70 artists from the late 18th through the early 20th century — primarily from the Met’s own holdings, along with a few from private collections — including paintings, drawings, photographs, prints, illustrated books and objects.

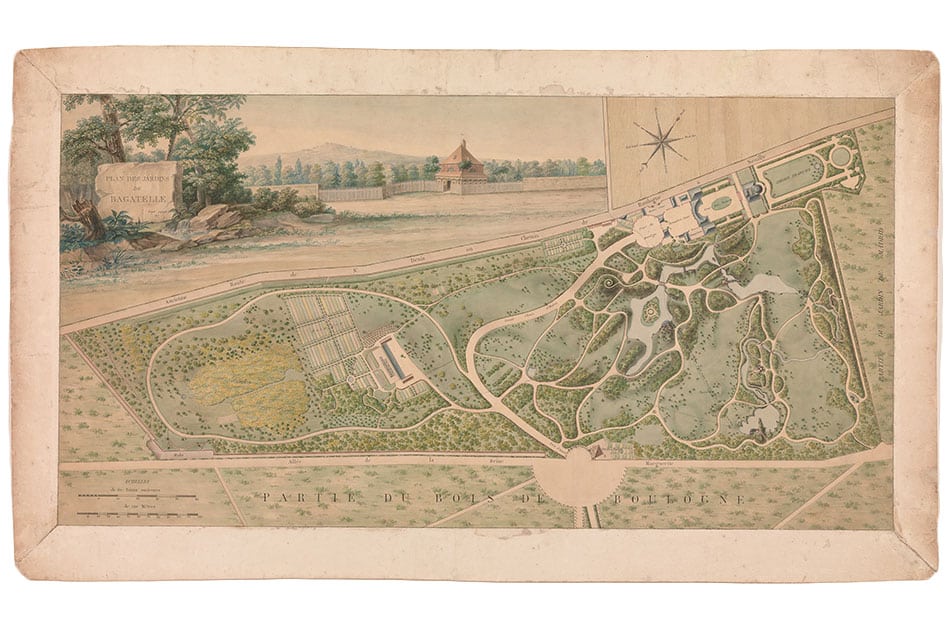

The exhibition is organized thematically in five galleries. “Revolution in the Garden” explores how the formal designs made famous by André Le Nôtre at Versailles and the Tuileries were replaced by the more picturesque style of 18th-century English parks and highlights the influence of the Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, Napoléon’s first wife, on the floriculture craze of the early 19th century.

The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil, 1874, by Édouard Manet

Garden at Vaucresson, 1920–36, by Édouard Vuillard

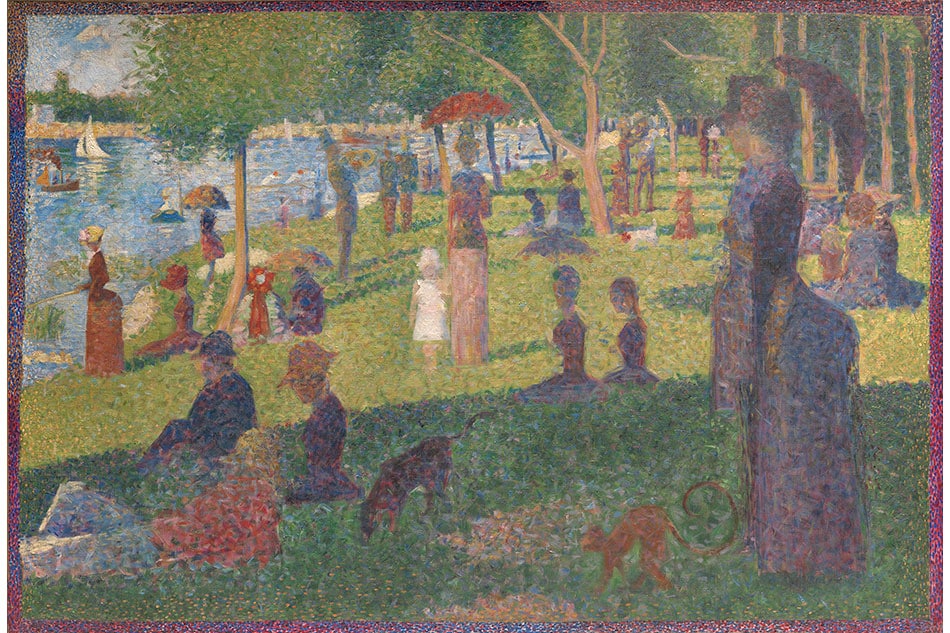

“Parks for the Public” displays depictions of the former royal parks, opened to the general population after the revolution, and the new green spaces created during Paris’s transformation into a city of tree-lined boulevards and esplanades under Napoléon III (who reigned from 1852 to 1870) and his master planner, Georges-Eugène Haussmann. This gallery features images of the Forest of Fontainebleau by such naturalist painters as Théodore Rousseau and photographers like Gustave Le Gray; paintings of the Tuileries by artists ranging from Honoré Daumier to Camille Pisarro; and views of the Parc Monceau (purchased by the City of Paris in 1860 and renovated as part of Haussmann’s grand urban design) by Monet, as well as a seductive version by Gustave Caillebotte. Other landscapes, such as those of Versailles and the Luxembourg Gardens, are interpreted by the legendary photographer Eugène Atget and the painters Berthe Morisot and Georges Seurat, who is represented by an 1884 study for his famous Sunday on La Grande Jatte.

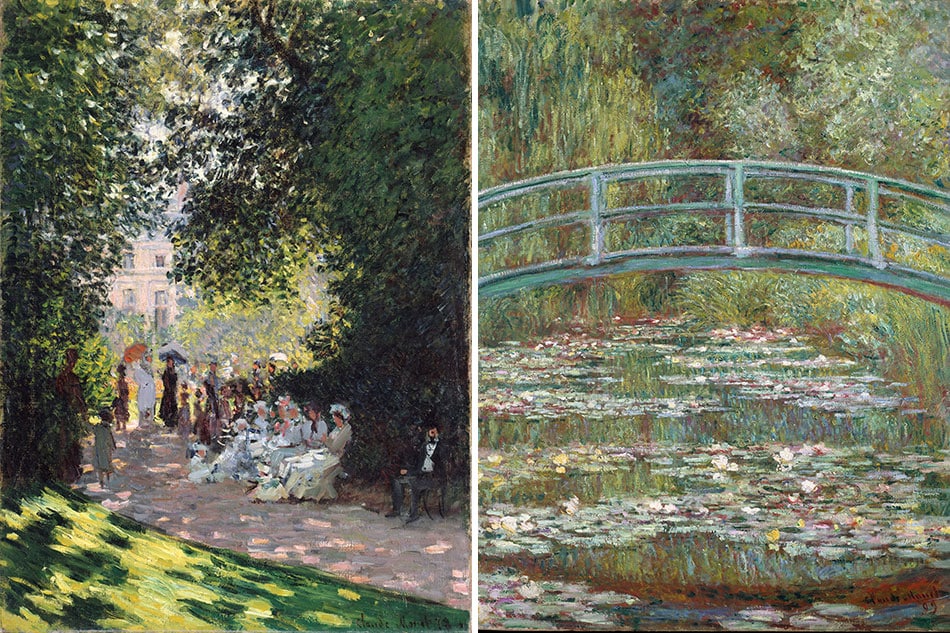

“The Revival of the Floral Still Life” offers an intoxicating parade of bouquets by Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Henri Fantin-Latour, Mary Cassatt and Henri Matisse, among others. “Private Gardens” and “Portrait in the Garden,” meanwhile, look at the backyard refuges that inspired artists to paint both landscapes and scenes of everyday life. Vuillard’s Garden at Vaucresson, begun in 1920, offers a casual glimpse of Lucy Hessel (his dealer’s wife) nearly hidden by plants as she gardens, with her cousin Marcelle Aron standing nearby in her dressing gown. Cassatt’s Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marly, 1880, is a similarly intimate close-up of the artist’s sister absorbed in needlework. This section also includes three iconic examples of Monet’s paintings of Giverny, the garden he called his “greatest masterpiece.”

Fittingly enough, the Met itself was built in Central Park, whose design was inspired by those of its 19th-century Parisian predecessors. This exhibition reminds us that in the modern world, green spaces are more precious than ever.