May 30, 2016French designer Pierre Paulin is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Centre Georges Pompidou, in Paris (portrait © Everd Soons for the Paulin Archive). Top: His Dos à Dos Face à Face ensemble, shown here in an indoor-outdoor space in the South of France, was originally created for the Louvre, in Paris. The set was recently editioned by Paulin, Paulin, Paulin, which is headed by the designer’s wife, Maia, and their son, Benjamin. Photo by Christophe Urbain for Paulin, Paulin, Paulin

The name Pierre Paulin has a constant companion in the word “groovy.” That adjective is almost invariably used to describe the late French designer’s best-known and most popular work: his seating pieces of the 1960s. Understandably so. With their cushy organic forms sheathed in stretchy swimwear fabric in Pop art colors and mod patterns, those Paulin chairs and sofas have a fresh and bouncy charm still evocative of the decade’s freewheeling days. Even the names of the designs — Mushroom, Oyster, Orange Slice, Tulip and Tongue — have a sybaritic ring. In many minds, Paulin is forever the Designer as Swinger.

Aficionados of his work are not cool with this. For them, the focus on one group of Paulin’s designs ignores the breadth of his accomplishments and the full scope of his innovation. But if Paulin has an image problem, a major retrospective at the Centre Georges Pompidou, in Paris — which runs through August 22 — should correct it.

The show, simply titled “Pierre Paulin,” covers the whole of a career that included furniture and interior design commissions for two French presidents and the Louvre and encompassed designs ranging from floor lamps and logos to steam irons and a postage stamp. “People have been looking at Paulin only through one window,” says Suzanne Demisch, coprincipal of the New York gallery Demisch Danant, which specializes in postwar French design. “There was so much more to him. There was a core architectural vision to his work. He pioneered techniques in production and ergonomics. He revolutionized seating, in a way.”

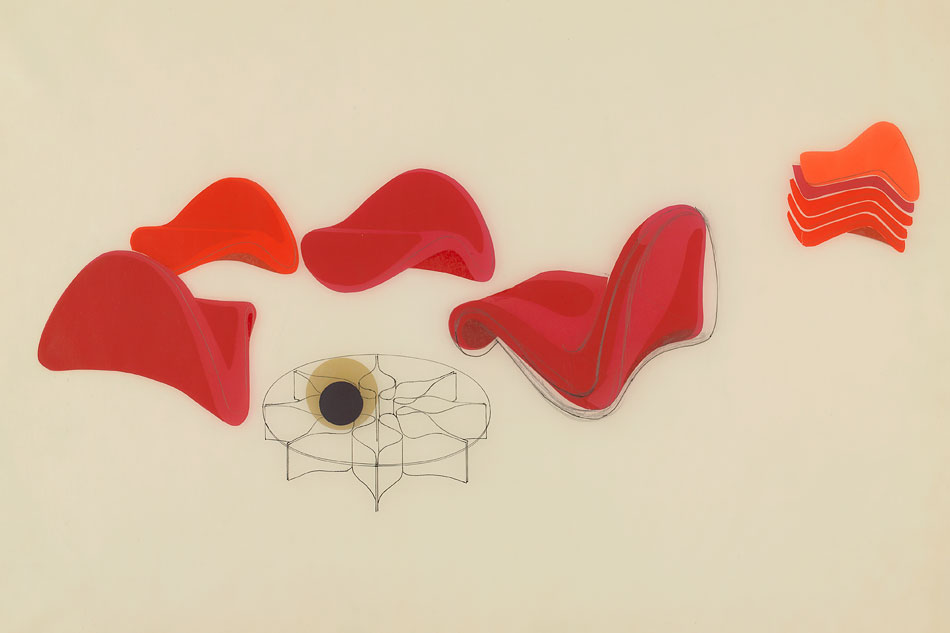

Paulin’s original drawings, including this 1960 concept for the Maison de la Radio, are also in the show.

Paulin was born in Paris in 1927 (he died in 2009); his father was a dentist, his mother, a Swiss-born homemaker. After he failed his baccalauréat — the entrance exam for the French university system — he went to Burgundy to train as a stone carver, with plans to become a sculptor. But an accident (or, by some accounts, a fistfight) left him with nerve damage in his right hand and unable to use his tools. So he enrolled in the Paris design school École Camondo, where he was exposed to the work of Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson and such Scandinavian designers as Arne Jacobsen. These were Paulin’s chief influences when he went to work in the 1950s for the manufacturer Thonet. The firm produced a series of geometric, steel-wire-frame chairs by Paulin, but not his designs for lush, organic-shaped seating.

Those concepts did, however, come to the attention of Kho Liang Ie, the young Indonesian-born creative director of the Dutch design company Artifort. In 1958, he recruited Paulin and encouraged him to develop furniture that combined strong but light materials in sculptural forms. Paulin’s first success with Artifort was the Mushroom chair, so named because its funnel shape resembles a chanterelle. In it, Paulin realized a compositional formula — tubular metal frame and foam rubber pad, covered entirely in elastic jersey fabric — that he later employed for such bold pieces as the bifurcated Orange Slice chair, the Möbius strip-like Ribbon chair and the legless, double-curved Tongue chair.

These pieces have become familiar, but their energy is still impressive. “One of the most important aspects of Paulin’s design was the sense of movement he brought to furniture,” says Robert Willson, of the Los Angeles design gallery Downtown. “His use of stretch fabrics creates a tension that suggests motion. Paulin’s furniture invites you to sit on it and experience the ride.”

In many minds, Paulin is forever the Designer as Swinger.

Paulin’s pieces continue to resonate in contemporary spaces. French interior designer Thierry Lemaire placed a vintage Tongue chair alongside newer furnishings in this bedroom in Portugal. Photo by Julien Oppenheim

By the late 1960s and early ’70s, Paulin’s name had become a byword in France for chic and progressive design. He was invited to create gallery seating for the Louvre as part of the renovation of its Denon Wing, and soon after he was commissioned to redesign four rooms in President Georges Pompidou’s private apartment in the Élysée Palace. Paulin’s extraordinary move was to cover the Napoléon III giltwood-paneled walls entirely in beige fabric and bring in newly designed pouf chairs, banquettes and aluminum pedestal chairs. (Madame Pompidou loved the look; the president not so much.)

Paulin cofounded an industrial design agency in 1975 and spent much of the rest of his career working for such clients as Renault and Air France. But in 1984, President François Mitterrand asked him to create new furniture for his private office in the Élysée Palace. (Philippe Starck was invited to design the bedroom suite.) Paulin took a postmodern tack. He devised a desk, finished in royal blue lacquer, that reinterprets a neoclassical bureau plat; sharply angular wood and cane office seating; and waiting-room pieces that look somewhat like attenuated Queen Anne armchairs.

In the mid-1980s, the Chicago firm Baker Furniture briefly offered a furnishing line based on Paulin’s designs for Mitterrand, but items like the inlaid bird’s-eye maple desk were too labor-intensive to be profitable. Apart from those he created for Artifort, few Paulin pieces were made in quantity.

“My father had a deep respect for the past,” says his son, Benjamin, who with other family members collaborated with Vendome Press on the definitive Pierre Paulin: Life and Work, to be published in September). “In the later years of his career, he wanted to go back to an artisanal way of production.” Timed to coincide with the Centre Pompidou show, the Paulin family will bring out limited editions of several idiosyncratic, never-produced designs, such as undulating sectional units that can be used to build a room-size sofa. These will be unveiled next month at Galerie Perrotin, in New York. Visitors will, inevitably, describe the designs as “groovy.”