August 4, 2019Pierre Cardin, 1974 (photo by Eddie Adams, courtesy of the © Estate of Eddie Adams and the National Portrait Gallery). Top: Models wear Pierre Cardin two-tone jersey dresses with vinyl waders, 1969 (photo by Yoshi Takata, © Pierre Pelegry).

From the 1960s through most of the 1980s, it was virtually impossible to open a magazine or newspaper without seeing Pierre Cardin’s name or the distinctive black-and-white PC logo. The French fashion designer’s attention-getting aesthetic — evident in his women’s, men’s and children’s clothing; furniture and home accessories; and hundreds of items like luggage, sunglasses, watches and ballpoint pens — along with his talent for self-promotion, made him a household name on several continents. And he’s still going strong at the ripe old age of 97, sketching new designs every day in his office on Paris’s rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

Raquel Welch in a Pierre Cardin outfit consisting of a miniskirt and necklace in blue vinyl and a Plexiglas visor, 1970. Photo by © Terry O’Neill / Iconic Images

The Brooklyn Museum is celebrating this “twentieth-century Renaissance man,” as curator Matthew Yokobosky terms him, with a major retrospective, the first in New York in almost four decades. “Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion” documents the designer’s seven-decade career with material drawn primarily from the Cardin archives. Yokobosky has chosen more than 170 objects (including 85 couture and ready-to-wear ensembles, plus accessories, furniture and lighting), presenting them in a series of circle-themed spaces inspired by the look of Cardin’s boutiques. Impressively, Yokobosky designed the exhibition himself. The product displays are complemented by archival photographs and images from the designer’s elaborate runway shows at venues like the Great Wall of China, Moscow’s Red Square and Cardin’s own theater in Paris. For context, clips from early films and television shows recall the “youthquake” era and its fascination with outer space and the future, which inspired the designer as well.

Born Pietro Cardin in Italy in 1922, he moved to France with his parents in 1924 and began his fashion career as a tailor’s apprentice at the tender age of 17. In 1945, he located to Paris, working for the couture houses Paquin and Schiaparelli before being hired by Christian Dior, where he helped conceive the legendary New Look collection of 1947. When Cardin left to open his own salon, in 1950, Dior sent flowers and referred clients to his young protégé.

The exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum highlights Cardin’s futuristic designs, including the 1966 From Finite to Infinity minidress (center) and the 1967 yellow Cosmocorps bodysuit and jumper (far right). Photo by Jonathan Dorado/Brooklyn Museum

The first Pierre Cardin couture collection debuted in 1952, and his futuristic looks were catnip for the free-spending consumers of the postwar years. He became an international celebrity with his Bubble dress of 1954, and the business expanded rapidly, attracting clients like Jacqueline Kennedy, Mia Farrow, Lauren Bacall and Jeanne Moreau. Perhaps his most significant achievement was introducing ready-to-wear fashion, a radical concept that would ultimately be adopted by every other high-fashion house. He was also a pioneer in marketing to Japan, China and countries behind the Iron Curtain.

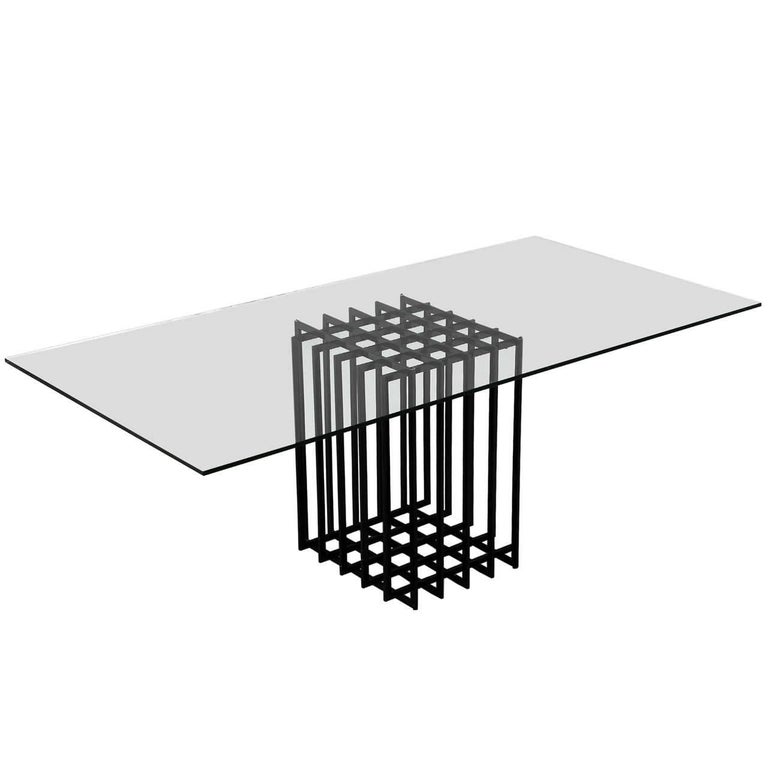

Although Angelo Donghia, in 1973, was the first designer to put his name on furniture, Cardin’s venture in the field was far more successful. He opened a custom furniture shop in Paris in 1975, and in 1977, he licensed his name for furniture, lighting and rugs that translated his fashion aesthetic into designs for the mass market. Cardin, who didn’t design the pieces himself, felt that furnishings were a logical extension of his brand: “Make sleeves to dresses or feet to a table, it’s the same thing,” he is quoted as saying. Covering the debut of his furniture collection — priced from $70 for a lamp to $1,375 for a cabinet — at the B. Altman store in New York, New York Times writer Rita Reif called it “the last word in chic,” then proceded to damn it with faint praise, noting that the glittery pieces, featuring chrome and aluminum, velvet upholstery and cubist lighting, would “appeal to those who prefer more elegance than originality in their modern.”

Cardine dress, 1968. Photo courtesy of © Archives Pierre Cardin

The home furnishings collections were the first of hundreds of products to bear the Cardin name or logo, including three automobiles and even an airplane; in 1986, Women’s Wear Daily reported more than 800 licensees. Cardin was widely criticized for diluting his image and that of couture fashion. Still, the licensing proved enormously profitable, earning the designer at one point a reported $10 million in annual income. The licensed furnishings were made for only about five years, but more than 300 licenses are still active today (the custom furniture endeavor also continues).

Cardin also expanded into hospitality, purchasing Maxim’s in 1981 and opening branches of the chic and popular Parisian restaurant in other cities, as well as adding a hotel division. His personal life was glamorous too. He threw lavish parties at his Bubble Palace (Le Palais Bulles), which he purchased in 1992 and transformed over 14 years with Hungarian architect Antti Lovag into a complex of 10 interconnected bubble-shape terracotta structures. The estate, on an expansive hilltop site overlooking the Mediterranean near Cannes, includes three pools, landscaped gardens and a 500-seat amphitheater. Cardin also owns a castle in Provence formerly inhabited by the Marquis de Sade and a Venice palazzo supposedly once owned by Casanova.

Lauren Bacall and Pierre Cardin with models on the set of Bacall and the Boys, a 1968 show profiling four designers (Cardin, Yves Saint Laurent, Emanuel Ungaro and Christian Dior’s Marc Bohan) and their fall collections. Photo by Yoshi Takata, courtesy of © Archives Pierre Cardin

Cardin has been the subject of several books and exhibitions at major museums, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, London’s Victoria and Albert and the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal.

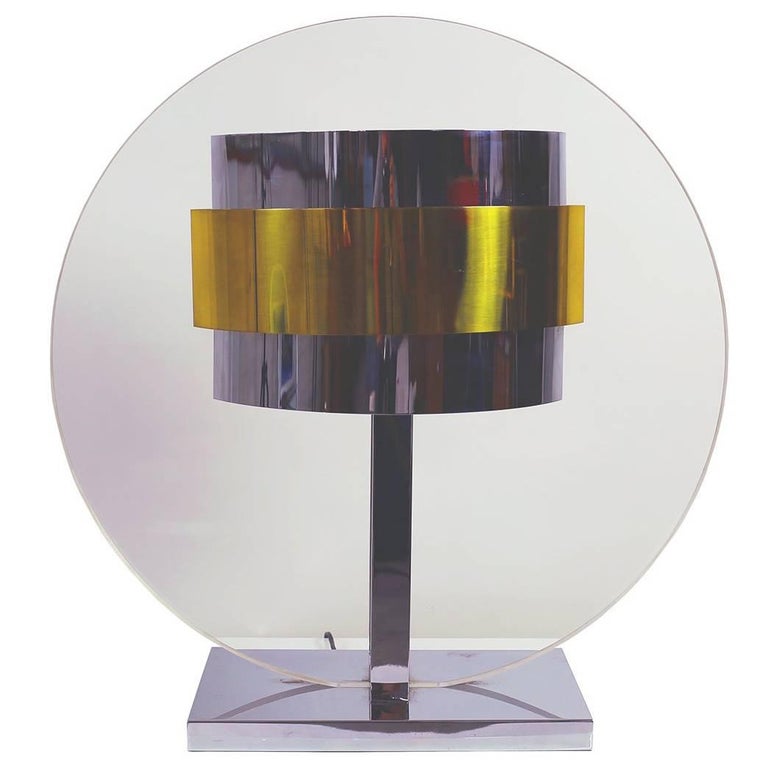

Satellite lamp designed by Yonel Lebovici for Pierre Cardin, 1969. Photo courtesy of © Archives Pierre Cardin

The Brooklyn exhibition, which runs through January 5, 2020, proceeds more or less chronologically, beginning with the first Cardin collection. It includes famous pieces like his Bubble, Target and Car Wash dresses and Cosmocorps unisex clothing and highlights the designer’s use of new materials like vinyl and heat-molded Cardine (his own invention) along with his clothing incorporating LED lights and glittery evening wear. There are no licensed designs. The furniture, all custom designs, primarily in high-gloss lacquered wood, include a credenza, desk and cabinet. The most recent objects represent Cardin’s ideas for men’s and women’s wear in 2019. “He’s so smart, and still dreaming,” Yokobosky says.

“I do not believe there has ever been a name as important as Pierre Cardin in the general history of couture,” the designer, never one for false modesty, has said. Cardin’s importance relative to other couturiers may be open to argument. But the universal recognition of his name and accomplishments cannot be denied.