January 22, 2018Author of the new monograph Timeless (Oro Editions), Boston architect Patrick Ahearn designs houses — like this gabled Greek Revival in the Martha’s Vineyard hamlet of Edgartown — that balance preservation with innovation. Top: For this H-shaped, gambrel-roofed house in the Vineyard’s Katama plains, Ahearn took inspiration from the shingle-style Gilded Age estates of the Northeast. All photos by Greg Premru Photography, unless otherwise noted

If you’ve ever spent time in Edgartown, Massachusetts — the exclusive Martha’s Vineyard enclave known for its 18th- and 19th-century Federal and Greek Revival architecture — you’ve likely seen the work of Patrick Ahearn. But you probably had no idea that he, or any other present-day architect, had a role in shaping what you viewed there. And as far as Ahearn is concerned, that’s exactly the point.

As he tells readers in his new book, Timeless (Oro Editions), which I had the pleasure to help him write, “If I have done my job correctly, I will be like a ghost who visits in the night — leaving no trace and most successful when no one sees my hand.”

The down-to-earth, preppily dressed Ahearn has spent the past three decades focused largely on the Vineyard, especially Edgartown, where he’s worked on more than 160 buildings, including several of his own homes. And over the course of his nearly 45-year Boston-based career, he’s developed a reputation for creating houses whose highly traditional architecture somewhat counterintuitively helps their owners lead highly contemporary lives.

His projects — whether the renovation of a landmarked 1682 Greek Revival former blacksmith’s home in Edgartown’s historic district or a new-build shingle-style estate in the Boston suburbs — proceed from a firm belief in the importance of context and an unwavering commitment to preservation. He doesn’t consider history a straitjacket, however. Instead, as he recently reminded me, he believes “the past is the key to the future. We have to look to the past to see how to do the future right.”

If there’s a secret to Ahearn’s success, then, it’s his ability to smartly balance historic preservation with contemporary innovation. He’s intimately familiar with the various vernacular styles of classical American architecture, including their most minute nuances, but he also appreciates the importance of making houses for the way people want to live now.

The entry of the yellow-clapboard Pease house — which still features the home’s original 1838 floors and balustrade — “immediately transports visitors back in time,” Ahearn writes. He replicated the design of the railing down a new flight of stairs to an added lower level, which was excavated during the restoration.

He may dress his projects with the antique floorboards and ceiling beams, carved case moldings, bubble glass, granite lintels and rubbed-bronze hardware of centuries past, but his interiors are characterized by plentiful natural light; easy, open flow from room to room; and strong connections between indoors and out. If those sound like modernist precepts, consider Ahearn guilty as charged.

Although his work today appears largely traditional — all gable and gambrel rooflines and white-clapboard or weathered-shingle cladding — Ahearn trained as a modernist. In the mid-1970s, he earned degrees in architecture and urban design from Syracuse University. (He now sits on the advisory board of the architecture school there.) And he grew up not in a home like those he now creates but an 832-square-foot ranch house in Levittown, the mid-century American ur-suburb on New York’s Long Island. These experiences weave their way into his work in surprising ways.

From Levittown, he says he developed an appreciation “for appropriate scale, and how the spaces between buildings can become just as important, if not more important, than the buildings themselves.” Levittown also provided insight into how the particulars of urban design — access to shared public outdoor spaces, bike and walking paths and yards that connect you to your neighbors — can foster a sense of community. That instilled in him a desire to create architecture for the greater good. As he writes in the book, he wants his buildings “to strengthen the urban and social fabric” of the places where he works and to improve “the lives of those who occupy, and interact with, them.”

After graduating from Syracuse, Ahearn spent time with some of the foremost modernist firms in the Boston area, not least the Architects Collaborative (TAC), a studio cofounded by Bauhaus guru Walter Gropius, and Benjamin Thompson and Associates, where he worked on the adaptive reuse of the 250-year-old shell of the city’s Faneuil Hall market, helping to turn it into the bustling shopping, culinary and cultural destination it remains today.

The H shape of the gambrel-roofed house in the Katama plains helps mask its significant overall size, as its wings make it hard to see the entire house from any one point. In the fictional narrative he created to help him design the building, Ahearn imagined it had been built in the late 1800s, then all but destroyed in the famed hurricane that whipped through the Vineyard in 1938. The story ends with his restoring the home to its former glory, decades after it was abandoned and left in ruins. Photo by Eric Roth Photography

“The past is the key to the future,” says Ahearn, seen here in Edgartown’s historic downtown, which he has helped to restore and re-enliven for a new generation of residents and visitors. “We have to look to the past to see how to do the future right.” Portrait by Randi Baird Photography

“What I learned from bigger urban design projects was largely about creating intimate outdoor space,” Ahearn recalls, “as well as a sense of portal, gateway and sequence — organizing the pedestrian realm. All that really applies, on a smaller scale, to how a house should be organized.”

In the residences he designs today, he arranges rooms along intersecting spines — galleries more than hallways — that provide sight lines down the length and breadth of a house before resolving themselves in beautiful views of sea and sky or dramatic architectural features, like a monumental local-stone fireplace. And he creates seamless connections from interior spaces to covered porches and on to terraces and lawns.

Ahearn makes sense of these spaces through what he calls “narrative-driven architecture,” a strategy that helps him balance preservation and innovation. For his own primary Edgartown residence, for instance, he conceived a small compound that looks as if it had been added onto and renovated over time. He began with the idea of a late-18th-century midshipman’s house with smaller, more formal rooms on the ground floor and bedrooms above, imagining that this was later expanded to occupy a barn behind that contains an open kitchen and great room. These structures form one side of a pool courtyard, beyond which sits a building that in the fictional narrative was a livery stable but actually holds a garage (which he prefers to refer to as a carriage house) at street level and a guest suite above.

Each building remains true to the scale and style of its neighbors — houses that actually are from the 18th and 19th centuries. But at the same time, the property offers the spaces a 21st-century family craves.

Recently, in the Boston suburb of Wellesley, Ahearn completed a home that borrows its cottage aesthetic from local Cape-style homes of the 1930s. Its U shape, with two wings extending off the back, serves to conceal much of its 6,000 square feet from the street. That’s a trick Ahearn frequently employs to ensure that a house’s scale “perfectly fits its context,” he says. Here, the wings have the added bonus of forming a private courtyard for a pool and cabana.

A new outbuilding Ahearn added to the rebuilt and expanded Chatham property takes its cues from the original 1910 structure and serves as both pool cabana and carriage house.

Now, Ahearn is working on a 26-acre estate in the town of Skaneateles, in Upstate New York’s Finger Lakes region, designing a new gatehouse and a tennis pavilion for it and renovating its historic 1920s-era boathouse, whose Arts and Crafts aesthetic he describes as “fanciful and fun.” In addition, he’s just started planning a new coastal compound for a client turned friend whose earlier house, in the Vineyard’s Katama plains region, features in Timeless. Developing a scheme for 11 acres on Edgartown Harbor, Ahearn will craft what he describes as “a whole village” — a stone-based, shingled main house plus guest quarters, a barn-like carriage house, a boat house and further outbuildings — to shelter multiple generations of the family “on campus,” as he puts it.

Although he’s approaching his fifth decade in the business, Ahearn shows no sign of slowing down, and the new monograph — his first book — is hardly a swan song. His 12-designer firm still works on upwards of 100 projects a year, and he’s already talking about another book.

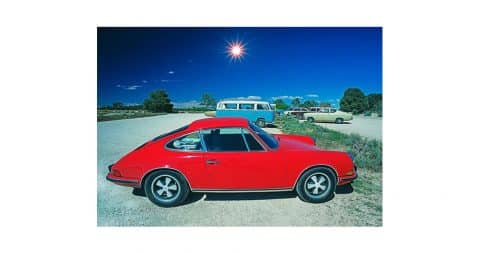

In his limited free time, he indulges his one passion outside of architecture: classic vintage cars. Ahearn has owned 300-plus over the years and has more than 20 now, the latest acquisition being a 1953 Studebaker coupe designed by Raymond Loewy. “I was on the hunt for it for fifteen years,” he says. “It’s one of the most important automotive designs of the twentieth century, and I finally found the perfect one in the perfect color combination: red with a white top and red leather interior.”

As with all things Ahearn, it’s the classic design details that matter most.

Patrick Ahearn’s Quick Picks

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore