December 16, 2018In her 35-year run as the editor in chief of Architectural Digest, Paige Rense was arguably the best-known design-magazine editor in the country. She transformed a high-end but rather staid journal of California architecture and interiors into an international chronicle of the homes of the rich, famous and stylish — and of the designers and architects who worked for them. AD had no aesthetic hang-ups: The over-the-top, Mayan-influenced Malibu beach house that Ron Wilson designed for Cher was just as important as the exquisite, art-filled Paris home of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. Whether you loved Rense’s approach or loathed it, AD was a must-read.

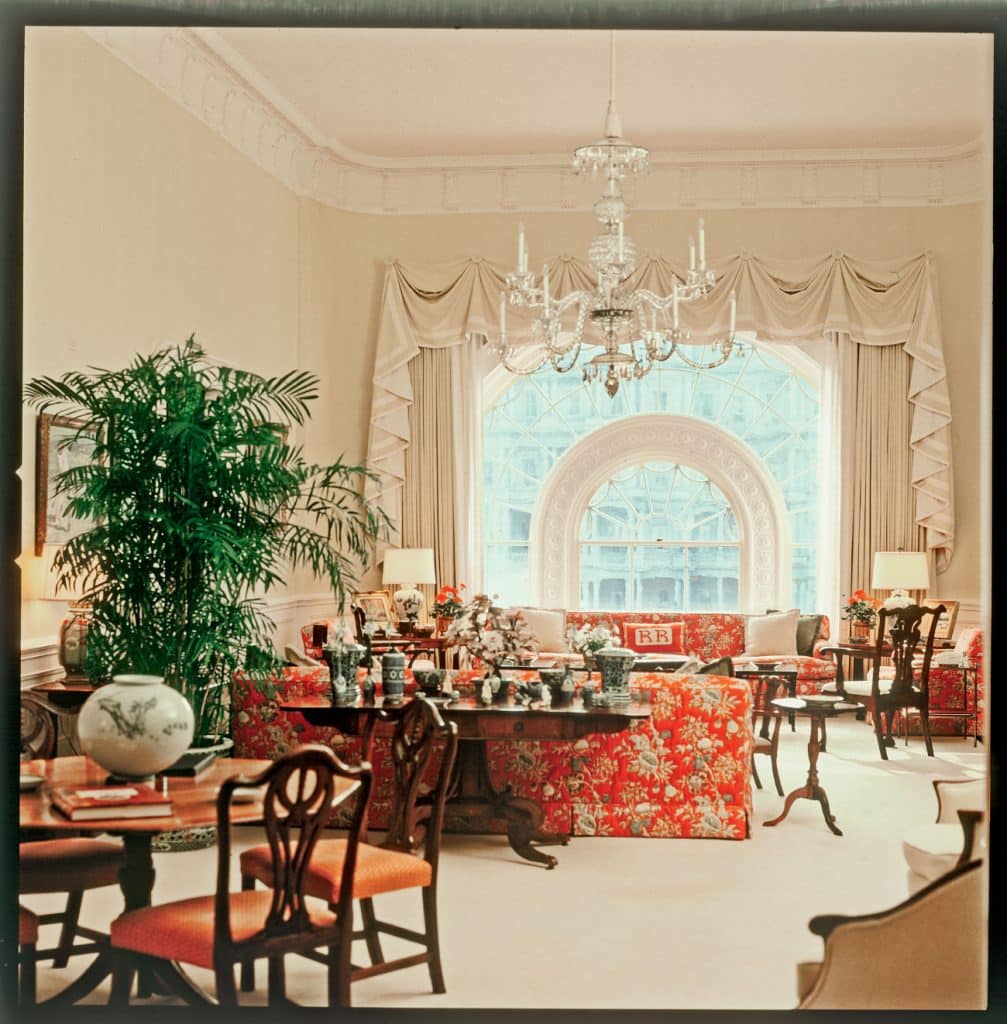

The new book by longtime Architectural Digest editor in chief Paige Rense explores the history of the magazine over its first nine decades — and shows off the homes it featured. These included (in the April 1986 issue) the Connecticut residence of designer Angelo Donghia, a sitting area of which is seen above (photo by Jamie Ardiles-Arce). Top: Frank Stella paintings hang in the dining room of Illinois-based designer and architect Richard Himmel, shot for a spring 1969 issue (photo by Yuichi Idaka).

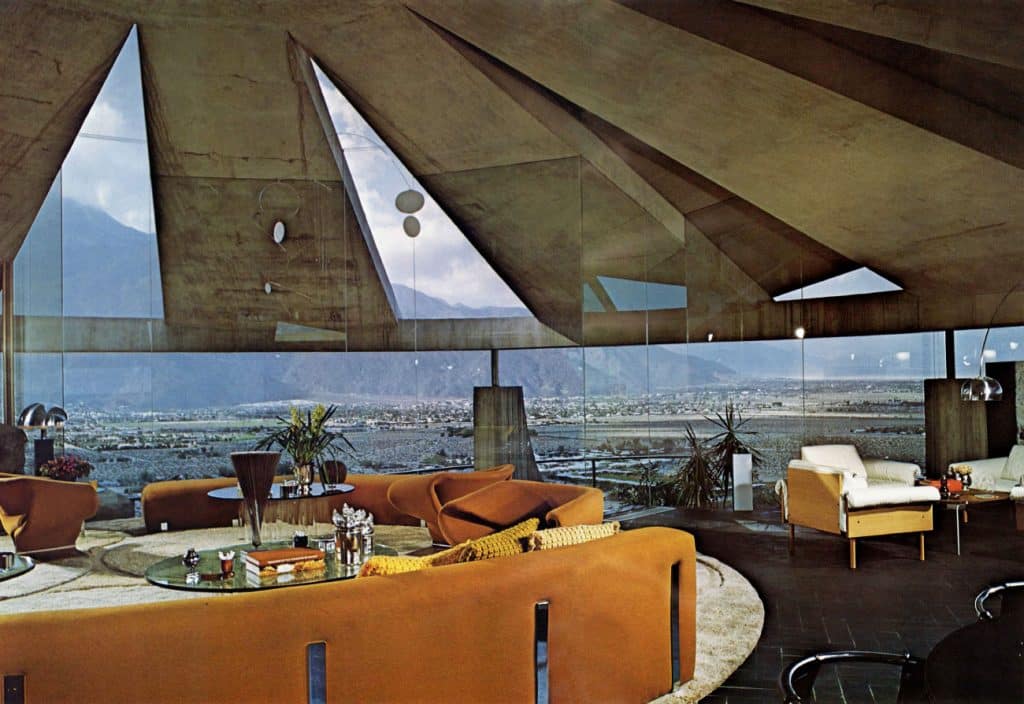

AD’s success was due mostly to Rense’s seemingly inexhaustible perseverance, as is evident in her new book, Architectural Digest: Autobiography of a Magazine, 1920–2010 (Rizzoli). The magazine was founded in 1920, as The Architectural Digest, by John C. Brasfield, a businessman enamored of California architecture and design. The houses featured were often designed by renowned architects like Wallace Neff, George Washington Smith, Paul R. Williams and Cliff May and owned by celebrities like Buster Keaton, Louis B. Mayer, Gregory Peck and Doris Day. The interior designers whose work was shown included Elsie de Wolfe, Frances Elkins, Tony Duquette and T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings. Brasfield believed in keeping the magazine high-end, emphasizing inspiration over how-to.

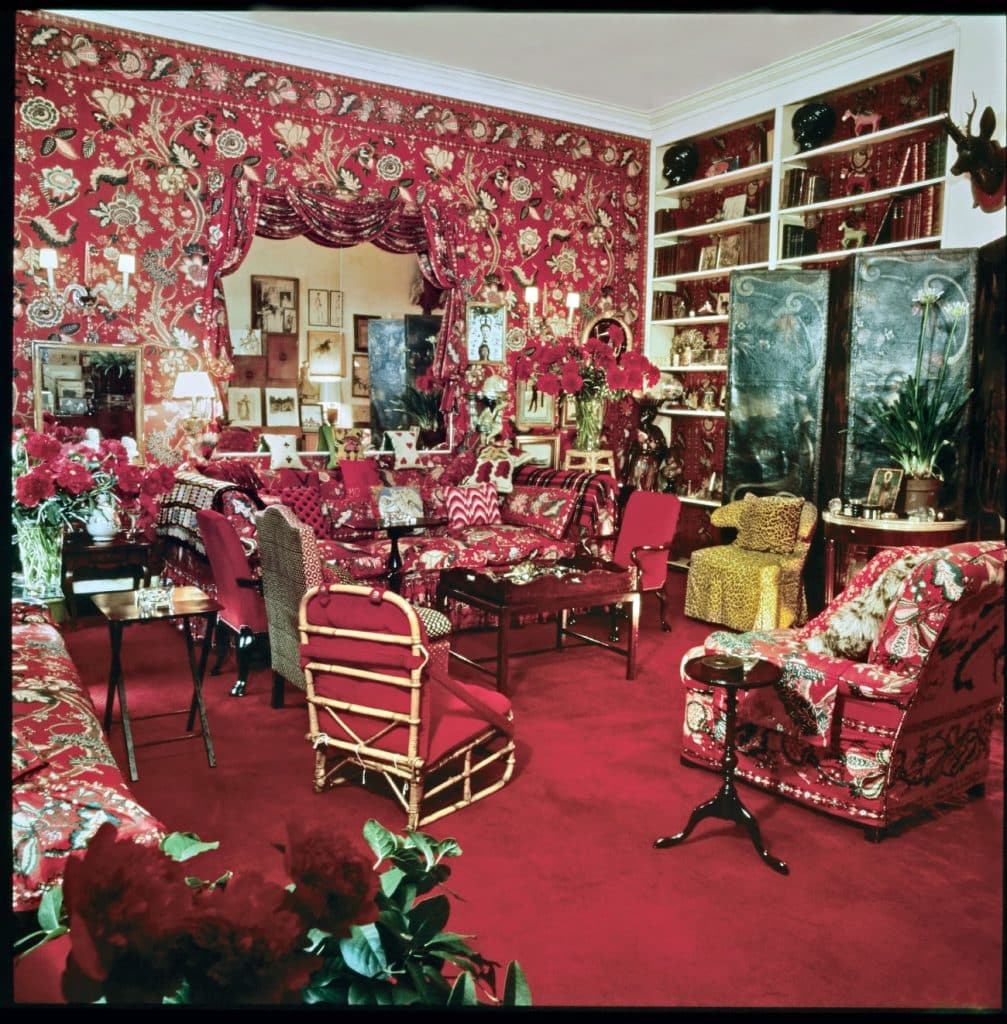

Left: The cover of AD‘s September 1985 issue teased its feature on what Rense describes as the “lavish, theatrical” Paris home of ballet star Rudolf Nureyev, designed by art director Emilio Carcano. Right: In October 1979, Rense took readers to the home of Britain’s Princess Margaret on the island of Mustique. There, Rense writes, “The open living room epitomized Caribbean living and was decorated with bamboo pieces and Victorian plates.” Photos by Derry Moore

After Brasfield’s death, in 1962, his grandson Cleon T. “Bud” Knapp bought the company that published the magazine, renaming the firm Knapp Communications. In 1970, the year the word the was dropped from the magazine’s title, Rense joined its three-person editorial staff. She became editor in chief five years later. Having come to the job with little design background, Rense made a point of introducing herself to top designers — first on the West Coast, then the East — and began immediately expanding AD’s vision. She added more international interiors, like Coco Chanel’s Paris apartment; argued for increased budgets to commission noted photographers and writers; and snagged exclusives on coveted projects like the designer Angelo Donghia’s Manhattan townhouse, which she refers to in the book as a turning point. “That was really the beginning,” Rense writes. “Once Angelo gave his seal of approval, other decorators — and even some architects — started paying attention and calling to tell me about their latest job.”

AD’s influence soon grew to the point where people offered Rense bribes to get their homes published, and one person threatened her when his house was turned down. Among the more distinguished “rejectees” was the billionaire Malcolm Forbes, who, when Rense declined to publish his Morocco residence, simply laughed and later delighted in telling the story to others. Ultimately, AD did publish some of the eight houses Forbes owned, and he and Rense became good friends. A 1981 cover story on the Reagan White House was a big hit, as was a 2010 visit to Jennifer Aniston’s Beverly Hills home, which was designed by Stephen Shadley; that issue sold 120,000 newsstand copies.

A flock of sheep by François-Xavier Lalanne makes itself at home in the Paris library of Yves Saint Laurent amid art by Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani. The console is by Le Corbusier. Photo by Pascal Hinous

Rense’s favorite designers include Mario Buatta, who wrote the book’s foreword (and who died in October at age 82); Jay Spectre; and Juan Pablo Molyneux, who once offered Rense and her guests a ride in a hot-air balloon at his château in France. The guests took him up on it, while Rense, she tells Introspective, “waved to them from my balcony in my nightgown.” Rense also adored the San Francisco designer Michael Taylor, who she describes in the book as “one of the greats, if not the greatest interior designer.”

Among her favorite homeowners: Forbes, Norman Lear and Gore Vidal. When Rense and her late husband, the artist Kenneth Noland, were in Italy, she asked Vidal if they might stay at his house in Ravello, on the Amalfi Coast. The writer replied, “Yes, stay forever.” Alas, Noland’s work required that the couple return to the U.S. before they could take up Vidal on his invitation.

William Randolph Hearst’s Northern California retreat, Wyntoon, got AD’s attention in January 1988. Bear House is one of several whimsical buildings on the property designed by Julia Morgan, who also created Hearst Castle, in San Simeon. Photo by Tim Street-Porter

Unlike other shelter-magazine editors, Rense did not send editors or stylists to photo shoots; the photographer worked directly with the designer or architect. “I wanted the designer’s viewpoint as expressed by the photographer, not me,” she tells Introspective. Rense writes in the book that she had no interest in “checkbook” decorating, preferring instead “a certain magic” in the places she published, and adding that “an emotional response is very important.” Concerned with animal rights, she banned items like tiger-skin rugs and hunting trophies from AD’s pages. The magazine published three of Rense’s own homes, including the one in Port Clyde, Maine, that she shared with Noland, but she was never revealed as the owner until now; all three are in the book.

“I wanted the designer’s viewpoint as expressed by the photographer, not me,” Rense says, explaining why she didn’t send editors or stylists on shoots, instead letting the photographer work directly with the architect or interior designer. Portrait by Kenneth Noland

As Condé Nast Publications was contemplating purchasing AD, in 1993, the company’s legendary chairman, S.I. Newhouse Jr., asked Rense, “If I buy the magazine, will you stay? She did stay, for another 17 years, until her retirement in 2010. Rense now lives in West Palm Beach, in a home she decorated herself. Ease is key — “style and period mean less than comfort,” she says — and so chairs are upholstered and have small drinks tables nearby. And because hues influence emotions, she used “a mélange of happy colors” with “no bright oranges or reds mixed together.” Nor is there any somber-toned furniture. Although she likes antiques, Rense says, “I don’t really care for dark brown wood.” When asked for her favorite object, she mentions a work on paper that Noland gave her the first time she visited his studio: “I would not part with it for a million dollars.”

Rense recently stopped her weekly Sunday suppers, preferring to see friends one-on-one “for a glass of Champagne and good conversation,” she explains. One thing is certain: Rense has no shortage of stories to tell.

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore