August 11, 2021When auction houses began selling NFTs for millions of dollars this past spring, many art enthusiasts wondered why this tech development mattered for the art world, aside from the conspicuous new crop of crypto investors entering the marketplace.

Some of the NFT sales making the most noise, after all, seemed to have little to do with art making, like the NBA video clips of game highlights, including a legendary LeBron James dunk, which last traded for $210,000, or the NFT of Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s first Tweet, which sold for $2.9 million.

But here is why they matter: NFTs have made selling and collecting digital art possible, and by doing that, they’ve revolutionized the way artists and collectors think about digital media.

Just as photography, prints and video art once were snubbed by the fine art establishment, digital art has taken a long, circuitous path toward acceptance by auction houses, galleries and fine-art marketplaces. The NFT, with its heady mix of high tech, high prices and alluring opportunities for extraordinary art making, has finally brought digital art onto the main stage, including 1stDibs, which has just launched a new NFT platform.

Digital art is hardly a new medium. Although Picasso in 1968 proclaimed computers to be “useless” because “they can only give you answers,” artists have been finding ways to push their creativity in new directions through technology since the 1950s (see “What Is NFT Art” for a digital-art timeline). Five of Andy Warhol’s mid-1980s graphic-art experiments performed on a Commodore Amiga 1000 computer were recently liberated from floppy disks and minted as NFTs at Christie’s, which sold them in May for a total of $3,377,500.

Contemporary artists of all stripes — from Damien Hirst and Urs Fischer to Derrick Adams, Lucas Samaras and Kenny Schachter — are now able to sell their digital work, create digital accompaniments to it or explore new creative avenues through technology.

Seeing the imaginative, intensely skilled talent in the digital-art community as technology advances is a refreshing reminder of the vast, ever-changing potential of the medium. This wasn’t possible before NFTs because there simply was no market for digital work.

“The world has been tipping more and more digitized and networked, and NFTs have helped to accelerate that in the art world” says Tim Whidden, vice president of engineering at 1stDibs and an early net artist, who has led the launch of 1stDibs’ new platform. “Digital art is a very wide range of media, from static JPEGs to 3D models and from videos to generative art.”

Aside from their creative merits, he adds, “one of the most important and interesting aspects of NFTs is that they make digital art viable in the sort of economics of traditional art by adding the elements of scarcity, ownership and provenance to digital images distributed via the web.”

1stDibs, which carefully curates and vets the digital art in its NFT collections, joins a growing field of established fine-art entities embracing cryptoart. Sotheby’s and Christie’s began selling NFTs this past spring, Pace Gallery launched a dedicated NFT platform in July, and Sperone Westwater has a hybrid exhibition of NFTs and physical artworks on view this month.

News also recently broke that the digital-art marketplace MakersPlace received a $30 million investment from members of the blue-chip-art-dealing Acquavella family and former Sotheby’s CEO Bill Ruprecht, along with other heavyweights from the worlds of art, entertainment and tech.

“It’s incredibly validating that digital artists are now able to monetize their creativity,” says Lee Mason, a U.K.-based virtual reality artist also known as Metageist, who made the leap into NFTs with his piece, Astro Shaman, in April 2020. 1stDibs tapped Mason to curate the inaugural selling exhibition for the site’s newly launched NFT platform, which will host biweekly themed auctions.

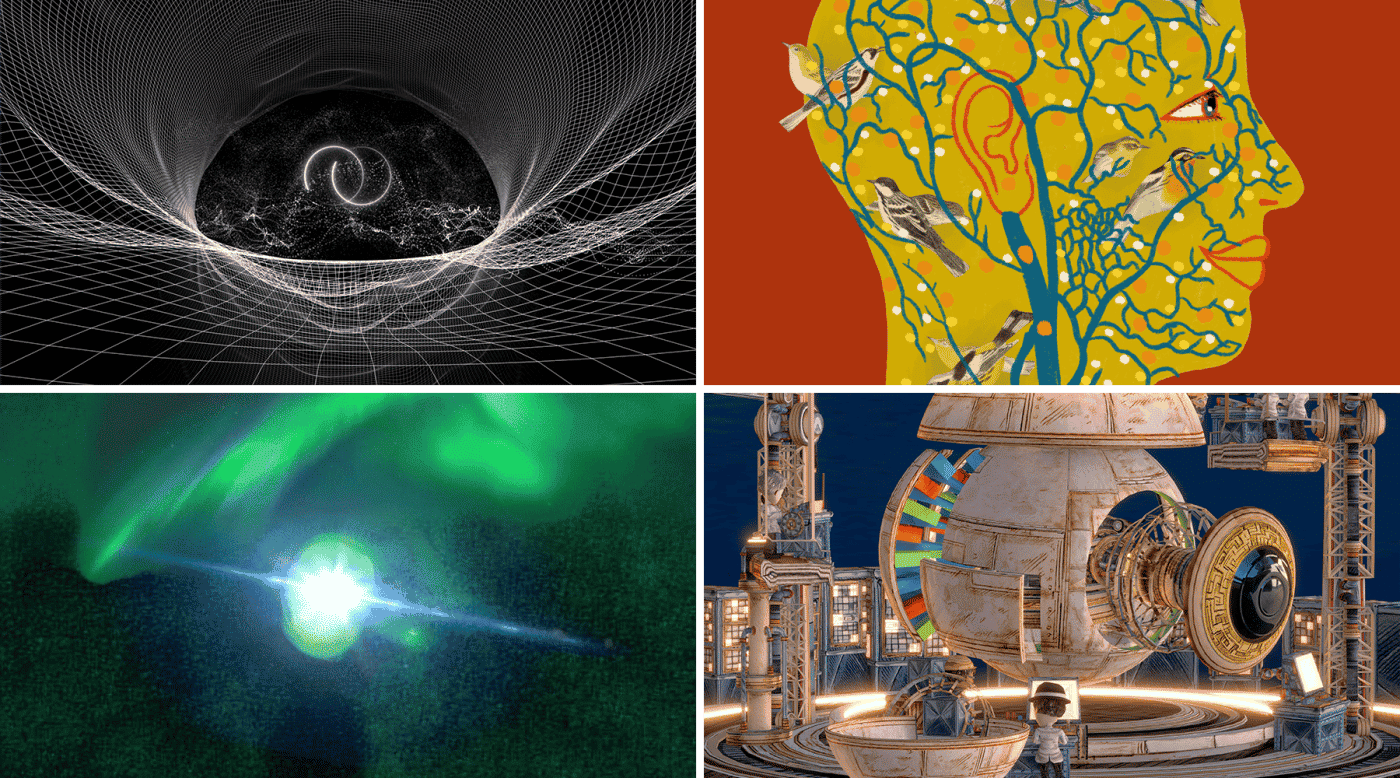

Titled “Portals: Art on the Threshold,” the exhibition, running through August 25, features the work of 10 digital artists (six in week one, four in week two), including Mason. Think of it as a new kind of space where art aficionados and tech enthusiasts can convene to witness how complex, beautiful and conceptually rigorous digital art can be.

For the uninitiated, an NFT, or non-fungible token, is a unit of data, stored in a blockchain (usually Ethereum), that includes proof of purchase, certification of ownership and verification of authenticity for basically any kind of digital file. Since the blockchain is a public ledger, collectors can see how much a work sold for and its current face value — a level of transparency rarely available in the conventional art market.

In some cases, artists can make royalties from repeat sales of their NFTs. While all this might sound far removed from the art world, in fact, an established contemporary artist — Kevin McCoy — is credited with minting the first NFT, in 2014, after developing the process with a coder named Anil Dash. (That work, a colorful pulsing octagon called Quantum, sold at Sotheby’s in June for $1.5 million.)

NFTs contain data that point to where associated digital items live on the web, but they can also be linked to physical objects. Hirst, for instance, recently launched a collection of 10,000 NFTs called “The Currency,” each of which corresponds to a physical dot painting. Both the NFT and the painting are included in the purchase, but buyers will eventually have to choose between the two, and Hirst will burn the rejects (a “burned” NFT is sent to a “zero address” account, effectively destroying the token and making it unrecoverable).

Mason, too, has included physical sculptures with his NFTs, such as a limited-edition set of small, cast brass- and pearl-infused resin orbs, or “Cyclopses,” with augmented reality capabilities, each accompanying a digital work from his series “The Hierophant.”

“I called the show ‘Portals’,” he says, “because it’s really at the crossroads of the physical and the virtual. 1stDibs, a company, a brand that sells physical items, is moving into the digital and entering a new space.”

The digital artists Mason invited to participate hail from around the globe and work in a wide range of styles, from the self-portrait-like clips that Rosie Summers, a British VR artist, animator and performer, makes of herself creating art in virtual reality to the crisp, colorful print-like forms of Isa Kost, an Italian illustrator, graphic designer and photographer who studied art and architecture and incorporates analog techniques in her digital art making.

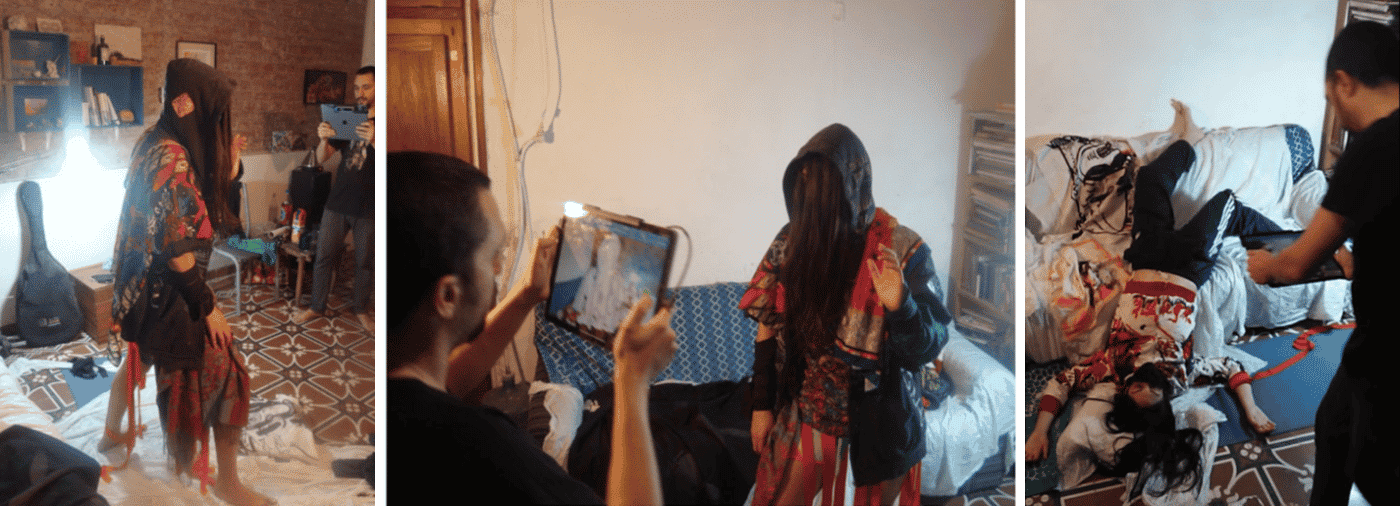

While the artists use different programs, tools and applications, none of the work is simply computer generated. It’s often as hands-on as any painting or sculpture, especially for those who make art in virtual reality, like Mason.

“This is not about sitting at a computer and coding,” he explains. “It’s entirely physical, gestural, and you see every tiny movement happening in real time, just like putting paint on a canvas.”

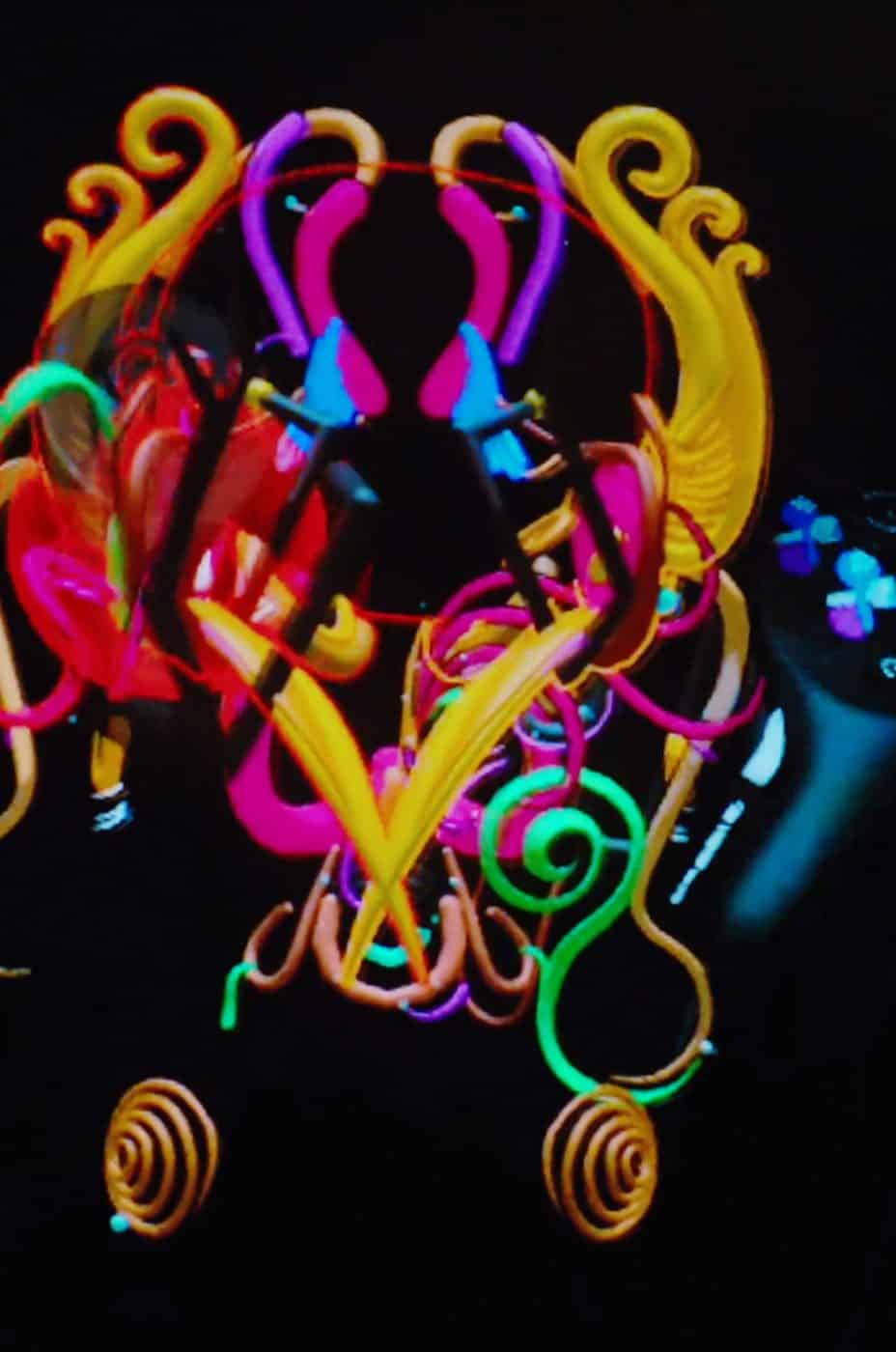

Indeed, seeing a virtual artist like Mason at work is like watching Jackson Pollock fling paint around. Mason, who has been inventing elaborate sci-fi narratives and sketching them on paper since he was a kid, has created two new portal-like works that combine his interests in nature and entomology with a biomechanical sci-fi aesthetic that summons one of his influences, Swiss Surrealist artist H. R. Giger.

Titled Sarracenia Vortex, after a carnivorous plant, the work consists of a hypnotic looping video playing within an ornately designed digital frame. It’s a bit like looking into a mirror and seeing another world — and the composition was, in fact, inspired by mirrors Mason says he saw for sale on 1stDibs.

“It’s entirely physical, gestural, and you see every tiny movement happening in real time, just like putting paint on a canvas.”

He’s also thinking about the strange new position humans occupy with the advent of virtual reality and the metaverse — a space anyone can enter with a VR headset. “I’m trying to acknowledge that this virtual world, the metaverse, is intensely alluring,” Mason explains, “but it needs to be regarded with some caution.”

He notes the environmental problems surrounding the “throwaway technology” of the popular VR headsets produced by Oculus (which Facebook owns), as well as the vast amounts of energy required to mine cryptocurrencies — a serious problem that Ethereum is trying to remedy.

Not surprisingly, there is a lot of crossover between the worlds of conventional and digital media. Argentine artist Lucas Aguirre, for example, studied painting at university and did a residency with a photographer for more than two years before discovering the pleasure of painting in virtual reality, as well as photogrammetry — a process that enables him to incorporate photographic images in his work — and 3D scanning.

He’s now able to combine all his talents, both analog and digital, in a time-consuming process, producing work that reflects a sophisticated understanding of space and perspective.

“Cryptoart, for me and for a lot of artists, is a way of reinventing ourselves. For the first time in our lives, we have control of our careers and can decide what to do, what to show,” he says, noting that in Argentina, wracked by years of instability and inflation and the devaluation of the peso, cryptocurrencies go especially far.

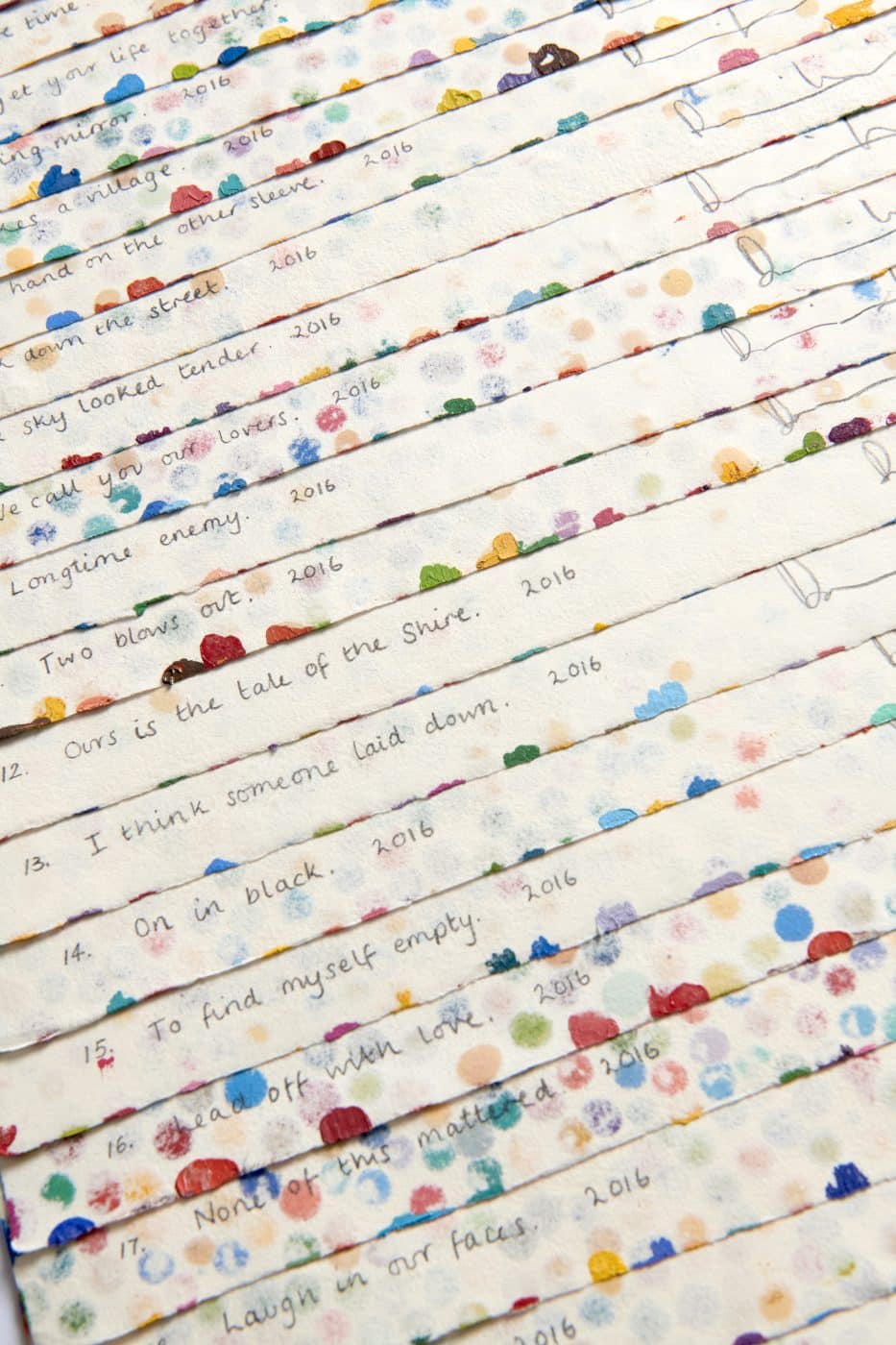

Ubicua (II), the richly layered video he has made for “Portals,” shows a shiny, reflective geological landscape into which he’s incorporated an image of his partner, floating in the abstracted space. It’s accompanied by a soundtrack produced by sound designer (and analog collage artist) Franco Bellavita, who is also based in Argentina.

“When I saw the piece it made me think of ice,” says Bellavita, “so I started digging and sourcing for scientific recordings of frozen lakes and glaciers and even sound from mammals under the ice, like seals.”

Viewing Ubicua is a fully immersive experience (and Bellavita recommends wearing great headphones). Not only has their NFT practice offered Aguirre and Bellavita unprecedented opportunities for creative collaboration, but being able to mint NFTs and get paid in crypto has been a lifesaver during the pandemic, when companies were scaling back on animation and other digital projects the artists pursued in years past.

Experimenting with VR was revelatory for the UK-based Ogi Damian, a motion graphic designer and animator who also draws, paints and sculpts. “Working in VR gripped me in an intense way,” he says. “It is so immersive. There are no distractions — no emails or phones. But there’s also this escapist dream world. And it’s visceral, and you feel it, and your mind remembers it.”

For 1stDibs, he’s debuting an elaborate animated film whose title, CHORISMOS TECHNE, is a Greek phrase meaning “the separation between idea and form,” says Damian, explaining that this refers to the creative process. The piece, which he’s been working on intensively for many months, shows a beautiful, glittering yet menacing futuristic world in which robotic humanoid figures seem controlled by a techno beat. It’s both dystopian and utopian, seductive and a bit frightening — not unlike the process of creating.

Part of the fun for him, Damian says, is testing the limits of the digital, and the richness of the meticulously detailed imagery speaks to that. The film clocks in at more than seven minutes — lengthy for an NFT — and consists of tens of thousands of moving parts. “I want to push the technology as far as I can until just before it breaks,” he says.

For the Spanish motion artist A.L. Crego, who has been making digital art for more than a decade, pushing the limits of the GIF — the image file we all know from our phones and computers — has become an artistic challenge. “I like having to create within its restrictions,” he says, comparing it to the constraints of painting inside a canvas.

Although he is known for bringing the work of street artists to life through animation, for “Portals” Crego has created a series of five black-and-white moving GIFs, each a kind of abstract representation of the human condition. The one titled Doubt, for instance, shows two glowing cosmic forms surrounded by a web of fractals and connected by a very thin line, seemingly repelling and attracting one another at once.

“It’s about the constant doubt one feels when meeting someone with different opinions, about oneself and the other,” says the artist, who is an avid reader of philosophy and cites Confucius, Jacques Derrida and Ludwig Wittgenstein among his influences.

For Crego, NFTs are a “natural step” in the evolution of his work. “I’ve been waiting for them,” he says. “People have been stealing my work for years and using it and not giving me credit. But that has all changed.”