November 30, 2015Above: Scandal Bag; History Feeds Mistrust, 2015 (detail), a self-portrait by Nari Ward, whose survey at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, titled “Sun Splashed,” examines the various ways he has spotlighted issues of displacement and injustice in North America. Top: Sun Splashed, Listri Sulla soglia, 2013 (detail). Images courtesy of the artist; Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins and Havana; and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

For Nari Ward’s first solo gallery show in New York, at Jeffrey Deitch in 1996, the artist brought the street into the white cube. Visitors encountered a storefront festooned with tropical fruit sodas and the words “Happy Smilers,” the name of Ward’s uncle’s 1970s band, which performed for tourists in Jamaica. Behind this awning and a soundscape of upbeat Caribbean music piped into the gallery, a real New York fire escape was suspended from the ceiling, flanked by two aisles of old appliances and furniture, bundled like cargo with fire hose, that lead to an altar of speakers emitting the sounds of rain and fire.

Happy Smilers: Duty Free Shopping is being restaged for the first time in Ward’s mid-career survey, “Sun Splashed,” on view through February 21 at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, coinciding with Art Basel Miami Beach from December 3 to 6. The retrospective includes a number of such experiential installations and monumental sculptures made from found objects plus photographs, videos and collages. Ward, 52, was inspired to make his Happy Smilers awning by the candy store downstairs from his first studio, in Harlam on 125th Street, which ran an illegal gambling operation. “I decided I needed a fake façade for my show,” he says. The display led viewers through a cliché of Caribbean culture into a more introspective space referencing ideas of migration — including Ward’s own, at age 12, with his family from Jamaica to New Jersey — as well as those of religion, struggle and ascension. “My early childhood memory of Jamaica after leaving was the rain hitting the tin roofs,” he says. The artist searched the Internet to find just the right sound and then loved how the recording unexpectedly also evoked the crackling of flames.

The wing-shaped Crusader, 2005, is reminiscent of the shopping carts that homeless people use to carry their belongings. Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Ward graduated from New York City’s Hunter College in 1991 and earned his MFA the following year from Brooklyn College, where he studied with the abstract painter William T. Williams. In 1993, during a stint in the artist-in-residence program at the Studio Museum in Harlem (a program founded by Williams), Ward was struck by the poignancy of a baby stroller abandoned in a crowded intersection at 125th Street. He ultimately amassed 365 discarded strollers into an elliptical installation that filled a former fire station on 141st Street he’d leased to exhibit the work, with an interior pathway carpeted by lengths of fire hose that viewers could walk on. (He moved into the building in 1999 and still lives and works there today, along with his wife and two teenage children.) Evocative of a womb or a ship’s hull, the piece, titled Amazing Grace — accompanied by Mahalia Jackson’s rendition of the song, which Ward’s father used to play — was simultaneously sorrowful and uplifting.

Shown again at the New Museum in the 2013 group show “NYC 1993,” Amazing Grace set the pattern for Ward’s approach of collecting and reworking found objects — such as shoes, bottles, tires and television sets — that are rich in symbolism and the aura of lives lived. The Pérez exhibition includes two sculptures built precariously on shopping carts — a regal chair titled Savior (1996) and a wing called Crusader (2005), constructed from chandelier parts, metal fencing, plastic bags, mirrors, clocks, trophy pieces and other bits of beautifully grungy detritus. Ward used both works in performances that he documented in videos, also on view, which probe both the visibility and invisibility of black men on the street. In an allusion to the way homeless people transport their possessions in shopping carts, Ward filmed himself in a nice suit and hat wheeling the Savior piece from his studio to a nearby Harlem church. “You’re pushing your belief down the street,” says Ward, who was drawing a connection between the redemptive power of creative and religious spaces. “I’m not really practicing, but I grew up a Baptist.”

Ward collects and reworks found objects that are rich in symbolism and the aura of lives lived.

Ward reoriented a liquor-store sign for Radha LiquorsouL, 2010. “I realized that within the word ‘liquors’ is the word ‘soul,’ ” he says. Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Also at the Pérez is Radha LiquorsouL (2010), part of Ward’s ongoing series of sculptures made from obsolete neon signs he removes from the façades of shuttered liquor stores. “I realized that within the word ‘liquors’ is the word ‘soul,’ ” he says. Ward reorients the signs and illuminates only the letters spelling “soul,” embellishing the works with artificial flowers, shoelaces and the tips of shoes that refer to the body without being literal. “I reconstitute the signs almost into a memorial direction,” he continues, noting how alcohol, or spirits, plays a role in celebration and religious rituals and also in the devastation of families.

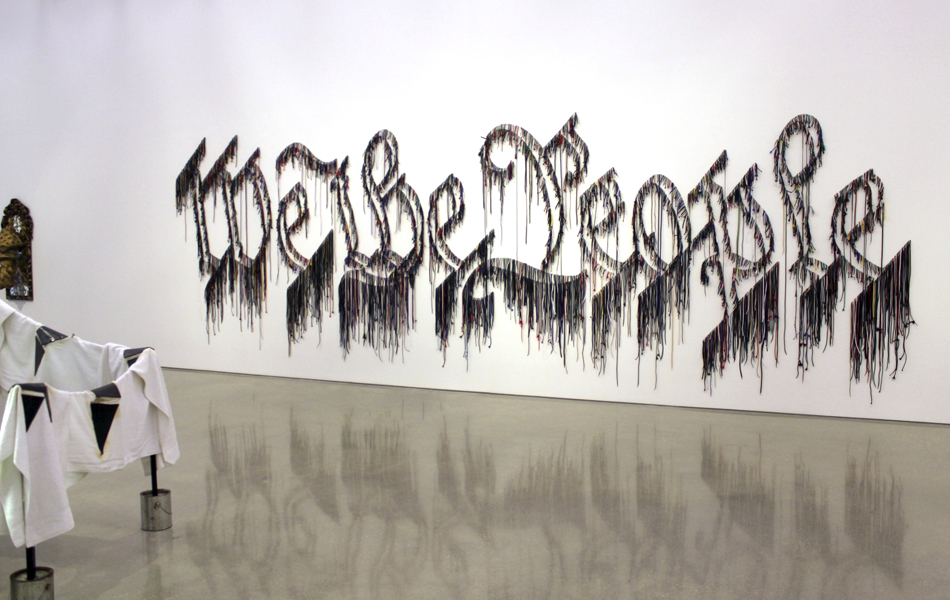

While Ward has spent most of his life in the United States, he became a citizen only in 2012, after years of beginning and failing to complete the bureaucratic paperwork. A number of pieces in the survey allude to the citizenship process, including Naturalization Drawing Table, first shown in 2004, with procrastinatory doodles scrawled over the INS form. Visitors to the show will have the opportunity to fill out the form and get it notarized on site with their picture taken and will receive a set of Ward’s editioned drawings in return. “If you give that test to eighty percent of Americans, they probably wouldn’t pass,” says Ward. Nearby, a 2011 wall work titled We the People, consisting of those words spelled out in shoelaces, apes the fancy script of the Constitution while evoking the 99 percent given voice by Occupy Wall Street and the issue of exclusion and injustice in this country.

Homeland Sweet Homeland, 2012, utilizes cloth, megaphones, razor wire, feathers, chains and silver spoons to proclaim the rights of citizens detained by police. Photo by Elisabeth Bernstein, courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Ward’s ongoing investigation of American inequality led him to elegantly combine the abominable history of slavery in the U.S. with the language of abstraction for his recent exhibition at the New York gallery Lehmann Maupin, which represents him. Three copper-covered wall works, each titled Breathing Panel, were perforated with holes forming a diamond with a cross inside that was surrounded by darkly patinated footprints headed in all directions. Ward first encountered this symbol repeated across the floor of the African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia. “It was a site for the Underground Railroad, and they were functional breathing holes for the slaves who were hiding in the church,” he says, adding that the symbol was derived from a Congolese cosmogram referring to birth, life, death and rebirth. “The sense of power and presence these things had — people underneath this floor — I wanted to use that symbol in a way that’s respectful and create another moment for the viewer.”

On the floor of the gallery, Ward laid a large rectangle of copper-sheeted bricks stenciled with quilting patterns. All nine geometric designs were based on navigational codes for runaway slaves. “These quilts would be laid out, and the people on the Underground Railroad would understand the secret language,” says Ward. Gallerygoers were invited to walk over the floor piece as though it were a minimalist sculpture by Carl Andre. “My mentor, William T. Williams, within his very formal work, had all these personal narratives. I like the idea of inserting Andre into the conversation, borrowing these modernist tropes and pushing it to another plane.”