July 14, 2024Naomi Campbell is more than a supermodel. She’s a cultural icon, a philanthropist and a changemaker who helped shatter entrenched ideas about beauty in the world of fashion. She’s also a trailblazer when it comes to championing Black talent and demanding more representation for models of color. And now, she’s the first model to have an exhibition dedicated to her at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Called “Naomi: In Fashion” and running through April 6, 2025, the show chronicles her incredible 40-year career.

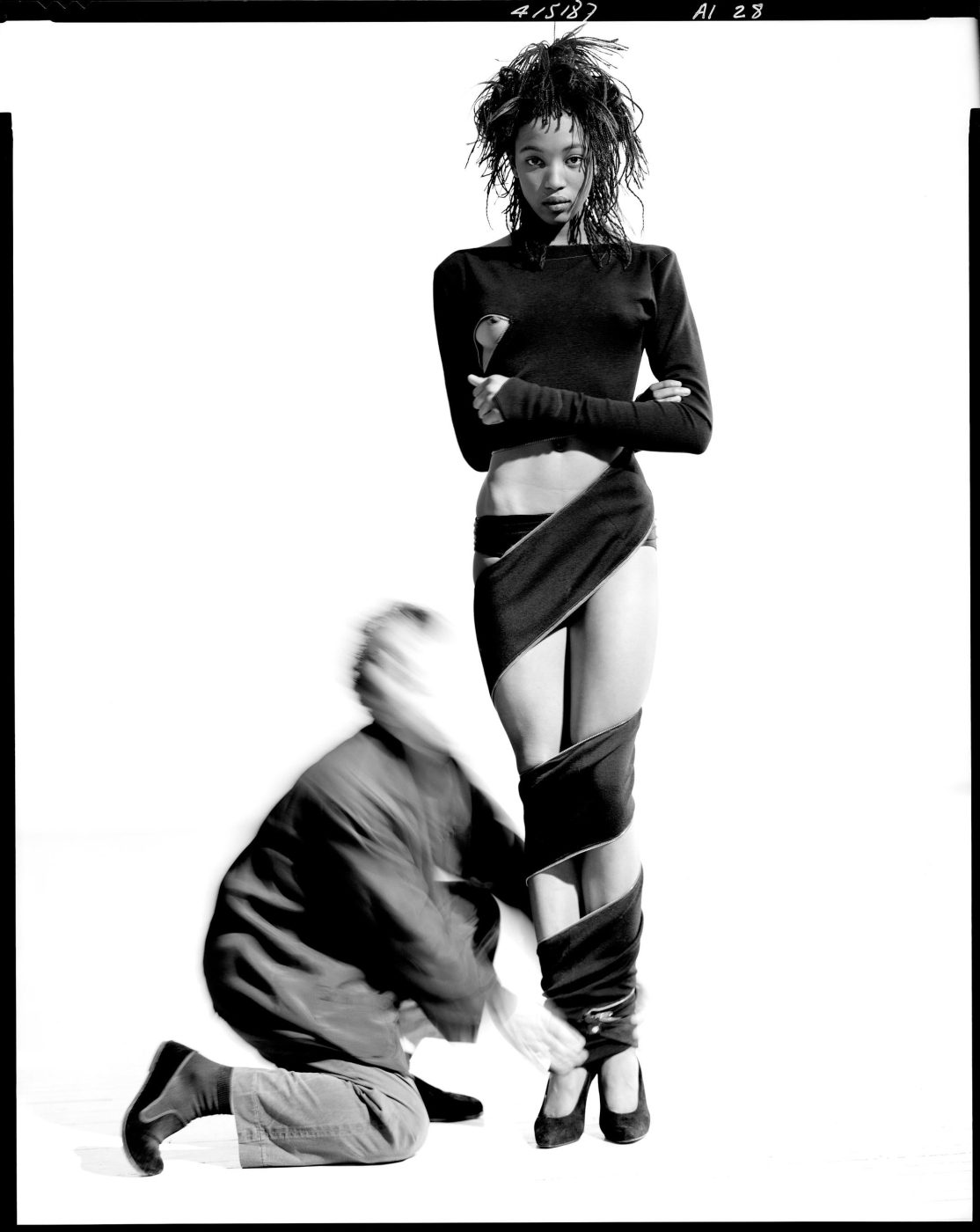

A former theater-arts student, Campbell was scouted by a modeling agent in London at the tender age of 15 while window shopping with friends. On the runway and in front of the camera, she drew on her love of dance and the stage to make clothes come alive, becoming an irresistible muse to many of the world’s most gifted designers and photographers.

Campbell made her debut magazine appearance, on the cover of British Vogue, in December 1987, photographed by Patrick Demarchelier in the desert wearing an embroidered gold silk jacket over blue silk breeches designed by Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel — an ensemble that is among the 100 looks featured in the exhibition.

Before entering this treasure trove of haute couture, visitors are presented with a huge plasma screen flashing images of Campbell on various runways, showcasing her trademark hip-rolling walk. It’s not just swagger — it’s sinuous choreography.

In his foreword to the exhibition’s accompanying book, former British Vogue editor Edward Enninful, who curated the show’s images, refers to Campbell’s unique energy as a combination of “captivating self-assurance, magical spontaneity and an instinctive understanding of how to move.”

Even when Campbell trips, she rises in the ranks of fashion mythology. Also on display are the staggeringly high blue Vivienne Westwood platform heels (all 12 inches of them) that the model was wearing in 1993 when she famously fell on the runway. The shoes have been reunited with the rest of the outfit — a navy velvet blazer, green tartan kilt, pink feather boa and white rubber stockings — for the first time since the tumble, sported by a mannequin sprawled on the floor in a pose similar to the one Campbell slid into. Arguably the most memorable image of the Westwood show was that of her giggling on the ground, an endearing reminder that supermodels — even those as formidable as Campbell — are human too. It shot around the world and only added luster to the brand and to Campbell, who revealed years later that other labels had subsequently asked her to reenact the mishap on their runways. (She politely declined.)

Equally arresting looks in the exhibition include the shimmering silver waterfall of a dress that Campbell wore in Sarah Burton’s final show for Alexander McQueen last October, as well as the huge black ball gown with engulfing funnel collar designed by Demna Gvasalia for Balenciaga’s Fall 2022 couture show, fit for an evil queen in a Tim Burton movie.

The exhibition abounds with vintage and modern designs from top-tier fashion houses like Fendi, Tom Ford, Jean Paul Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana. But beyond the incredible craftsmanship on display, it is full of delightful insights connected to epic fashion moments. The “fembot” bustier that Campbell wore for Thierry Mugler’s Buick ready-to-wear Fall/Winter 1989 show, for example, was inspired by the front of a car, with headlight bra cups and a metal grille on the front.

Then, there’s the Gianni Versace Andy Warhol dress that Campbell wore on the designer’s Spring/Summer 1991 catwalk, a figure-hugging technicolor silk gown emblazoned with the faces of Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. Versace had his models sport their last runway looks out on the town, so she wore this to a dinner in Milan with the designer and her fellow supermodels. By that time, she had appeared alongside Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington in George Michael’s cultural-milestone “Freedom! ’90” music video. Versace created history’s most memorable supermodel catwalk moment when he had the same foursome walk his Fall ’91 show linking arms and lip-syncing the song.

Another notable look is the exuberant feathered cocktail dress that Campbell wore for her first Yves Saint Laurent haute couture presentation, in 1987, which marked the beginning of their close friendship. Saint Laurent, known for regularly casting Black models, helped her make history as the first Black woman to appear on the cover of French Vogue by, according to Campbell, threatening to pull his advertising if she didn’t get the gig. Campbell, by virtue of her own passion and resolve, went on to become the first Black model to appear on the covers of TIME and Russian Vogue and to lead a Prada campaign and open a Prada show, among many other pioneering accomplishments.

The writer and activist Michaela Angela Davis sees Campbell as less a muse than a creative collaborator, one who “activates clothes in a way that gives them electrifying new life.” And certainly, Campbell’s ability to transform for the camera and give fashion a “charge” is a personal trademark.

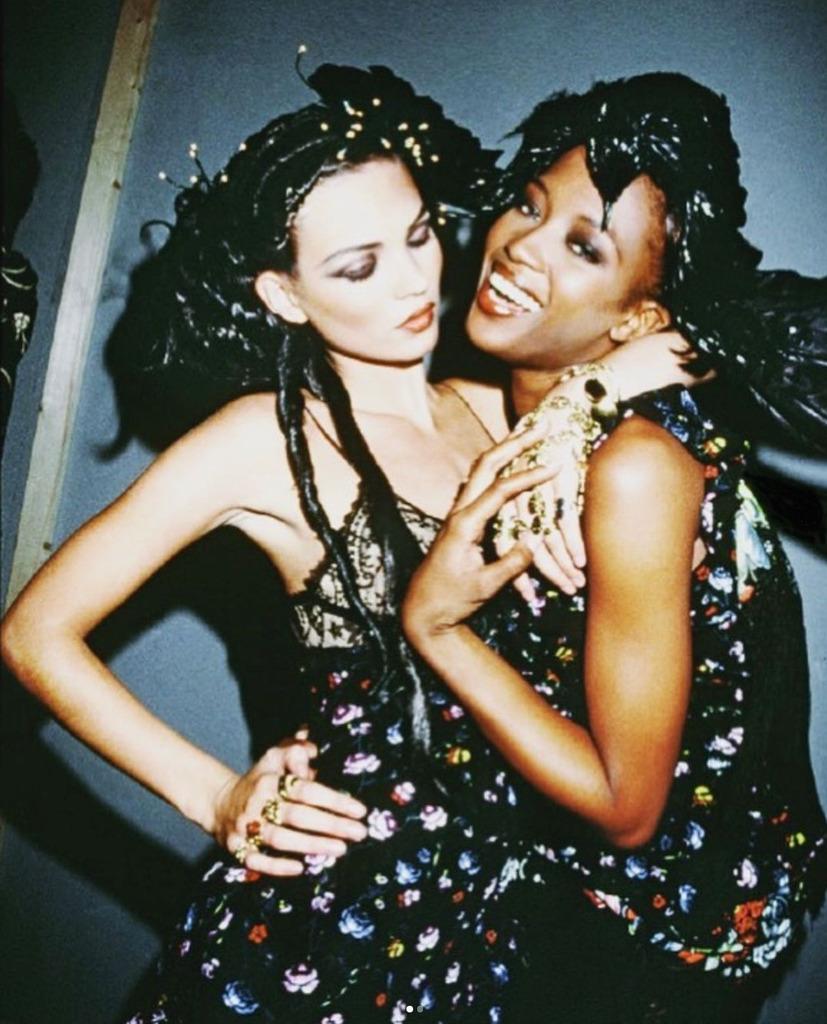

She has worked with influential photographers — among them, Peter Lindbergh, Herb Ritts, Arthur Elgort, Jean-Paul Goude, Helmut Newton, Ellen Von Unwerth, Steven Meisel, Roxanne Lowit and Albert Watson — to produce a rich repertoire of powerful images. For Unwerth, she was teasingly sultry. For Elgort, balletic and powerful. In front of Lowit’s lens, Campbell was the animated party girl with the broadest smile, immersed in the heady 1990s fashion scene.

They all saw something magical in her, but she strived for perfection, too. In the exhibition’s audio commentary, she explains, “I started out very shy, but I was willing. And when you are willing, that’s all that really matters. I wanted to know how to pose, how to stand, to understand the skill of how to be a great model. I wanted to learn.”

Campbell has often spoken of the close bonds she forged within and beyond the fashion industry. She refers to Nelson Mandela as her “honorary grandfather” and speaks of the support and mentorship she has received from members of her “fashion family,” including fellow supers like her lifelong friend Kate Moss. Designers John Galliano, Westwood, McQueen and Lagerfeld, along with photographers Lindbergh and Meisel, played significant parts in her development.

Undoubtedly, Campbell’s closest relationship was with the late Franco-Tunisian couturier Azzedine Alaïa, whom she met when she was 16 and spending the summer in Paris on assignments for French Elle. Alaïa was immediately enamored with the young Campbell and took her under his wing, giving her a place to stay and making sure she steered clear of trouble. A surrogate father to her (she affectionately called him “papa”), Alaia saw in Campbell the poise, grace and discipline of a dancer and placed her at the center of his runway shows starting in late 1986, helping to launch her career. The designer famously said that, to him, Campbell had the “perfect body,” strong and sculptural. It inspired many of his figure-hugging dresses, including his affectionately titled Mon Coeur est à Papa red dress from 1992.

The exhibition honors this three-decade-long friendship with a room of Alaïa wonders, including a zip dress, famously photographed in 1987 by Arthur Elgort, and a white corset dress with gold fringe, inspired by Campbell’s dance training, in which the model twirled around for his Spring/Summer 1988 show, where she also performed a solo tap dance sequence. Many of these outfits are on loan from the Fondation Azzedine Alaïa, whose president is the editor, gallerist and fashion maven Carla Sozzani, who describes the relationship between couturier and model as “instant love.”

“Azzedine saw something pure, innocent and beautiful in Naomi. She was so young then,” Sozzani tells Introspective. “His private apartment is located over his atelier, and in this apartment is a little mezzanine, where he installed a bed for her, which is still there to this day. Staying there as she did, Naomi learned fashion. She could see Azzedine sewing, pattern cutting and draping the clothes on her. She participated. She is one of the few models who understands the magic behind the making of couture.”

This being a very personal dive into her fashion history, Campbell worked with V&A fashion curator Sonnet Stanfill to style a vitrine inspired by her own dressing room, complete with workout wear, magazines, Dolce & Gabbana lingerie and antibacterial wipes, referencing her reputation as a germaphobe. Among these personal items is her lucky Alaïa metallic mini dress, which she installed herself ahead of the V&A opening.

This dreamy exhibition offers evidence that Campbell herself is just a little bit in awe of all the opportunities life has offered her: A cabinet is devoted to her beloved keepsakes, all in pristine condition, including her first Concorde ticket, from 1994; her original Yves Saint Laurent model pass; and her Elite model agency card from 1989. So, she may be a supermodel, one who’s been known to be temperamental and even a bit of a diva at times, but she’s super sentimental, as well, which makes her relatable. She’s also wholeheartedly in love with what she does, and perhaps that’s the magic, or swagger, that she brings to everything she wears.