January 5, 2020Photographer Mitch Epstein first picked up a camera in 1969, but the pictures he took then, like all his work, could have been shot yesterday. A protégé of legendary color photographer William Eggleston, Epstein gravitates toward seemingly disparate themes that capture the American ethos in both personal and more general terms.

Photographer Mitch Epstein’s new book, Sunshine Hotel (Steidl), brings together 175 of his images, all of them — like West Side Highway, New York, 1977 (above) — chronicling the American zeitgeist. Top: Ivana Trump and New Jersey Generals Cheerleaders, Trump Tower, New York City, 1984

He has looked at the demise of his father’s furniture store in the series “Family Business” (2003) and explored the symbolic and literal aspects of American power in the series of that name (2009), using images of energy-producing plants. He has also focused on the complex relationship between nature and civilization in “New York Arbor” (2013) and “Rocks and Clouds” (2015). His new book, Sunshine Hotel (Steidl), offers a deftly curated selection from his complete oeuvre, all characterized by the timeless and multifaceted beauty Epstein is known for.

Left: Nogales, Arizona: Sonora, 2017; Right: Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., 2007

The 175 photos (some never before published) composing the volume are arranged in sequences of varying lengths. The title is taken from the name of an SRO hotel around the corner from his longtime home and studio just off New York City’s Bowery, an area that has very much shaped his life as an artist. “Sunshine Hotel is about going to a metaphorical place that exists only in this book,” says Epstein, who encourages readers to look closely at each page to uncover the connections between the images. Yancey Richardson, one of his longtime dealers, seconds that advice: “Mitch makes images that are both compelling to look at and sophisticated in content, so they reward your attention on multiple viewings.”

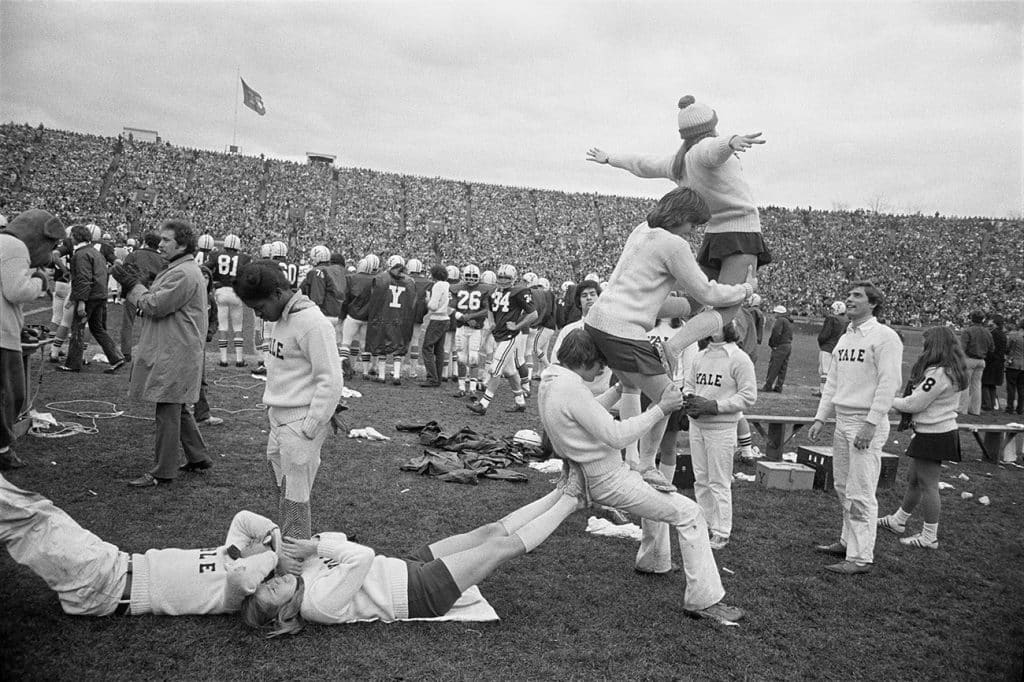

Yale Bowl, New Haven, Connecticut, 1976

Introspective recently sat down with Epstein, who had just flown in from Hawaii, where he was covering indigenous groups’ resistance to the construction of the world’s largest telescope.

You exhibit in galleries, and your photos are often mural scale, six by eight feet. How do the pictures translate into book form?

My prints are the works of art. By the time I start making a book from a body of work, the individual pictures have already survived my critical editing process and formed a series. I ask myself, “Do they work on their own terms, not just as part of the series? Do they hold the wall at scale?” One of the first things I consider is how can the book be a vessel to hold the multiple narratives within the series, and a distillation of a project.

Warehouse, Epstein Furniture, Holyoke, Massachusetts, 2000

What’s interesting about Sunshine Hotel, and meaningful to me, is that it is not coming out of a project. The photographs are drawn from my long history of making pictures in and about America. The one theme common to all of the work is that it’s made in America.

Your work has addressed potentially loaded themes, especially ones related to the environment and immigration, as in your recent “Property Rights” series. In these highly politicized times, how do you avoid your pictures’ coming off as heavy-handed?

The pictures ask questions — they are pointers. But I don’t ever think about message, because message leads to making work that is reductive and one-dimensional. I’m interested in making pictures that are layered. They may suggest a point of view, but every reader will bring their own experience and set of associations to the work.

Biloxi, Mississippi, 2005

There is a picture that I made in Biloxi, Mississippi, six weeks after Hurricane Katrina. The photograph portrays a site where a house once stood. The house is gone, with only the foundation remaining, and there is detritus lying everywhere, including a mattress impaled on a tree. But the photograph is complicated by the golden evening light that illuminates the tree and coastline. Within the picture frame, beauty intersects with terror to create a more complex and enigmatic image that’s not simply “ruin porn.”

Untitled, New-York, #10, 1996

How do you want your readers to experience this book?

I hope that my readers will take the time to read it, to pay attention not only to the individual pictures but to how they are juxtaposed in novel and surprising ways to conjure up America as a place and an idea. Each sequence has its own visual logic, while the fourteen sequences themselves are set in a precise order to produce a crescendo over the course of the book.

Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota, 2018

Can you walk me through your reading of one of the sequences? Although there is a title plate in the back, the book has no captions, so it really is up to the reader to look and figure out the puzzle, as you mention.

The opening photo of a windswept road on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation sets a certain tone. It’s bleak, but there is a car with its headlights on in the distance. The second spread has a picture of a surveillance camera looking at the island of Manhattan on the left, and on the right is in an interior from my “American Power” series, in which Boots Hern has set up a surveillance camera in her window, because she’s living in the shadow of a coal-fired power plant and has been harassed by the company.

Left: Untitled, New York #11, 1997. Right: Beulah “Boots” Hern’s House, Cheshire, Ohio II, 2004.

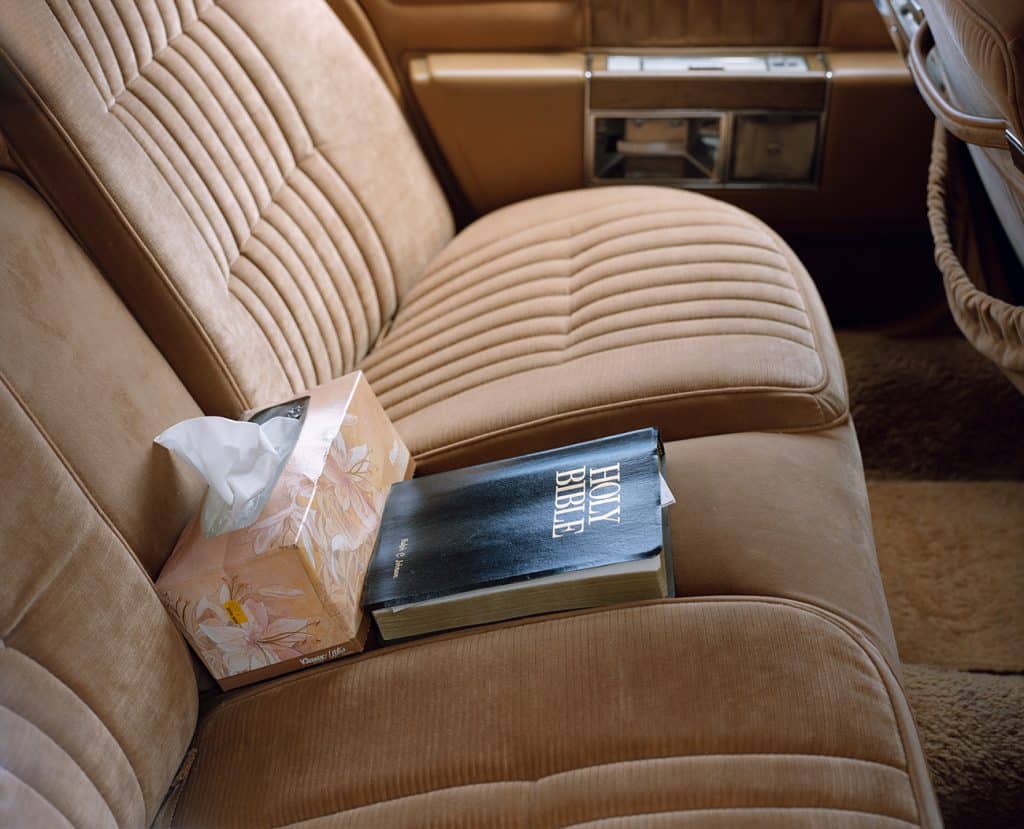

So you have surveillance on the outside looking in, and then you have surveillance on the inside looking out. The following spread begins with a picture of the border wall, and on the right page is a picture of the Lincoln Memorial, with concrete bunkers protecting its periphery. The final photograph in the sequence is of a car interior in New York City, where a Bible sits adjacent to a Kleenex box on the plush backseat. This short sequence has many readings: the anticipation of the open road, the unbridled security and surveillance pervading our society and, finally, faith.

You have shot documentary and feature films. How has your film work affected your photography?

With film, I learned to think about narrative and drama in new ways, and how to stage and direct what was transpiring for the camera without losing its authenticity. Those lessons have been put to use in my photographic practice, where I will alter what’s in front of the camera if it will enable me to create the picture that I’m interested in making. I’m not a documentarian, and much of my work hovers between fact and fiction.

Chalmette Battlefield, Louisiana, 1976

Lastly, I know that sometimes your projects are a reaction to the preceding project. Can you explain?

South Beach Dredging Site, Fort Pierce, Florida, 2005

I am more interested in what I don’t know than what I do. That has led me to a more protean practice, where I’m constantly switching my subjects, tools and materials to expand myself and my work. This has helped me to continue to feel an urgency to make new work. I don’t want to be beholden to the past.