September 25, 2017Michele Oka Doner’s Soho loft is part living space, part laboratory. On the left is Totem, 2007–15, composed of wax, organic material and stainless steel; on the right is the terra-cotta Hestia, 2010. Top: Oka Doner stands among her finished pieces and works in progress.

On a warm summer morning, Michele Oka Doner glides through her enormous duplex loft in Soho like a cross between Georgia O’Keeffe and Martha Graham, an ethereal vision in her daily uniform of off-white or black drapey dress over leggings, her dark hair pulled back in an elegant chignon. Unmistakably beautiful at 71, Oka Doner says she never gave her appearance much thought. “The fact that other people do is always a surprise to me, because I’ve never considered looks my strong card,” she says. “I was five foot eight, practically, in junior high school, and that was not an asset in those days, so I developed myself in other ways.”

That is something of an understatement. Oka Doner’s artistic practice, inspired by the natural world, is far-reaching, stretching from sculpture, photography and video to jewelry and furniture design. She has even cowritten a memoir of her hometown, Miami Beach: Blueprint of an Eden. Her new monograph, Everything Is Alive (Regan Arts), published this month, is the first book to fully document several major public and private commissions, and her latest exhibition, “Into the Mysterium,” opens at the Lowe Art Museum in Miami on October 12.

Her loft, where she has lived and made art for 36 years, is a magical trove of raw materials and completed pieces. Towering works on paper hang near round bronze tables surrounded by circular benches and topped with monumental, branchlike candelabra, all of her own making. Surfaces are covered with intriguing collections of natural objects and archeological finds: minute bird skulls, fossils, stone tools, shells. “I’m a hunter-gatherer,” Oka Doner says.

This handmade staircase was in place when Oka Doner and her husband bought the loft. The space also features pieces by Oka Doner, including the Celestial chair, on the left, and One Eye, installed on the wall. Leaning against the center wall is The Wounded Healer.

Growing up in Miami Beach, where her father was a judge and then the mayor, Oka Doner loved watching him preside over the courtroom, but it was his passion for the outdoors that had the deepest impact. “My mother had no interest in nature. She didn’t want to get dirty,” Oka Doner recalls. “As busy as he was, my father would pause to watch a bird sit in a puddle after the rain. He’d stop for a sunset. He paid attention.”

Her mother’s side is responsible for her artistic bent. Oka Doner’s grandfather Samuel Heller painted the ceilings in the original Metropolitan Opera House, on 39th Street in Manhattan, and her aunt Dorothy Heller was an Abstract Expressionist who trained under Hans Hofmann and exhibited in prestigious galleries, including Tibor de Nagy and Betty Parsons, but shunned the scene at the movement’s Cedar Tavern hangout. “She didn’t get along well with people,” Oka Doner says. “Her work is not known, but it’s fabulous.”

She describes her mother as having a chic sense of style, both in fashion and decor. “She was a minimalist before there was a word for it,” Oka Doner recalls. “Ours was a curated home. That was unusual.” Oka Doner inherited her mother’s devotion to setting the table and arranging flowers, “all of which I considered a ceremonial aspect to enjoying daily life.”

Oka Doner’s instinct to integrate art and design was nurtured at the University of Michigan, where the art program was folded into the school of architecture. She took to clay right away because it felt like wet sand. “I always built things on the beach,” she says. “We dug down so we could make a pond. Then we would take out big chunks of sargassum seaweed and shake them over the pond. You wouldn’t believe what would come out — tiny shrimp, baby crabs and beautiful little sargassum fish.”

Her student works included imaginary seeds and fruit. She began pushing the limits of the medium, combining wet clay with shards from someone else’s fired and broken pot. “You can’t do that,” she says. “It has to be the same, or it’s going to shrink apart.” But the seam that opened up at the juncture, evoking the earth’s topography, did not faze her.

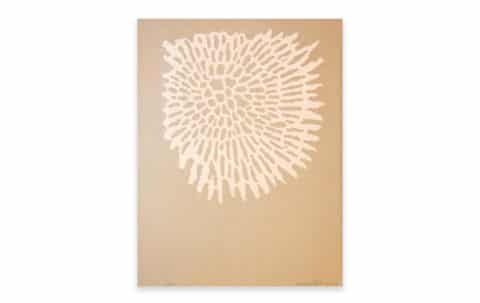

From left: Hominin, Burnt, 2015, and White Star II, 2014. In the background is a detail of the 2009 drawing for a sculptural scrim fabricated in steel for a project in Doha.

Her work evolved to include disturbingly tattooed, armless porcelain dolls — although the assignment was to make three jars with lids — then ceramic body parts, seeds and pods. Following graduation, she stayed in Michigan, building a kiln herself in her backyard and finding success with shows at the Detroit Institute of Arts and PS1 in New York.

After 12 years in Detroit, however, Oka Doner felt she’d outgrown Michigan. In 1981, she and her husband, Frederick, then an advertising executive, moved with their two young sons to New York, lured by Soho’s spacious live/work lofts and tight-knit art world. (Now retired, Fred manages the business side of his wife’s studio.)

“I wanted to come in and be part of the dialogue,” Oka Doner says. “You can’t work in isolation. We weren’t meant to as humans. We evolved in communication with others. The interdependency is wonderful. New York had that to the nth degree — to infinity, practically. You feel part of a community and part of a family here, which I think is more important than people understood it to be. The Freudian myth of the [solitary] artist is way past.”

In New York, she continued to invoke human, animal and plant forms, reinforcing the links between them with life-size headless bronzes seemingly made from coral or tree bark. At the same time, her practice developed beyond sculpture to, among other media, beguiling works on paper, often embedded with organic material, which are represented by Marlborough Graphics and available on 1stdibs.

Oka Doner has become best known for her public artworks, some three dozen of which are on display across the country. Unlike the vast majority of public art, unassumingly dotting parks or anchoring plazas, some of Oka Doner’s pieces are seen annually by tens of millions of people passing through heavily trafficked, high-visibility locations, such as the Miami International Airport, the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and the 34th Street–Herald Square subway station, in New York.

Her first public piece, though, was for a quieter spot: a historic Michigan cemetery that was the final resting place for many American war veterans. After the carnage of the Vietnam War, Oka Doner’s 1979 proposal for the tree-lined graveyard was simple — a fallen leaf.

This area of the studio, which contains Oka Doner’s 1995 Radiant Disk table surrounded by Carlo Bugatti chairs, serves as a place for meetings, discussions and writing.

As her commissions grew in magnitude, she wove together two threads from art history. The first was the WPA era of the 1930s and ’40s, when the government program paid artists, including Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, to produce public murals and sculptures. The second was Europe’s grand tradition of incorporating art from floor to ceiling, whether in soaring cathedrals or ornate palaces. “When I moved from Miami to Michigan in 1963, I had spent many summers in Europe, and I had seen what I call the room as a work of art,” she says. “Not like where I grew up — art was still something that was hung on the wall over the couch.”

She perceived a continuation of this tradition in Diego Rivera’s landmark 27-panel installation Detroit Industry murals enveloping an entire gallery in the DIA, which she calls a “masterpiece.” “I saw this harking back to the long tradition of the room being the work of art itself,” Oka Doner says.

She had the chance to put her own spin on the concept in the late 1980s when she won a national competition for the Herald Square subway station, a major transit hub. “I wrote only a two-paragraph proposal,” she says, describing her idea “to create an inversion, to descend into light instead of darkness.”

Her concept for Radiant Site, meant to give commuters a rare moment of Zen, comprised a 165-foot passageway whose walls were covered with 11,000 ceramic tiles in varying shades of gold. Organizers were concerned about graffiti artists, who were prolific in that decade. “I said, ‘No, you don’t understand. People do graffiti where things are dirty and neglected. It’s an angry response to their not being cared for. Nobody’s going to touch this wall. I’ve made a sacred space.’ In almost thirty years, it’s never been damaged.”

Her public — she prefers Lewis Mumford’s term civic — artworks had something of a domino effect. One featuring cast-bronze sculptures embedded in the floor of the Evanston, Illinois, public library, for instance, begat another, for the Sacramento Central Library. That, in turn, led to an invitation to participate in the competition for the Miami airport project, which Oka Doner won with her submission of an eight-foot-long drawing.

She began work on A Walk on the Beach in 1991 and didn’t finish until 2010, because each time the airport expanded the concourse, officials asked her to keep going. The work now stretches a mile and a quarter and encompasses thousands of unique bronze sculptures inlaid in a terrazzo floor along with a sprinkling of mother-of-pearl, which Oka Doner explains does double duty, evoking sea foam and serving as a framing device.

Each sculpture riffs on an ocean creature. “Initially, I started walking the beach and picking up things I thought would make interesting pieces. But you get to a thousand pieces, and it’s not happening anymore,” says Oka Doner, who then found inspiration in photography books picturing microscopic organisms.

“In Europe, I had seen what I call the room as a work of art. Not like where I grew up — art was still something that was hung over the couch.”

More boggling than the sheer size of the work is the fact that Oka Doner fashioned each wax model herself. “I had a rhythm,” she says, explaining that she devoted her mornings to Miami and afternoons to other projects. “I’d end up each day, if I was lucky, with maybe six or seven pieces [for Miami]. I’d have [an assistant or two] with a heat gun clean the edges. I got quicker. I got better.”

Her furniture designs, which are represented by David Gill Gallery and available on 1stdibs, evolved from her lifestyle, she says. “I needed a table, I made a table. Then, somebody liked it and asked if they could have one. All of the work that functions arose from my initial need. The chair is the exception. The chair for me was always a philosophic essay.”

In ancient times, when most people sat on the ground, Oka Doner continues, the chair’s elevation served as a metaphor. Perusing the chairs in the Egyptian galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, their seats inlaid with ivory, bone and ebony, affected her thinking. “To them, it wasn’t art, it wasn’t design,” she says. “It was life itself.”

Other cultures have influenced her as well. “The Scandinavians: If you’re going to make a wooden spoon, pick the wood carefully, make it beautiful. The Japanese: Their cups were their works of art,” she says. “The separation of work that was made for its ‘own sake’ was pretty recent in our wiring.”

Oka Doner’s designs, she admits, are made “for the eye,” not the back or derriere. Her first chair came about because she had two pieces left from Celestial Plaza, a commission for the American Museum of Natural History, so she put them together. “I didn’t think about comfort.”

Perhaps most remarkable is that, although she lives in the most urban of American cities, Oka Doner remains firmly connected to the natural world. She rises from her chair and returns with a small fossil stone inscribed with the forms of tiny ancient invertebrates, a gift from an old friend. “I used to look at it, and one day she gave it to me,” Oka Doner says. “I have these segmented worms in my dining room table. I chose a fossil marble for that. There’s a lot of that all around me here. So when people say, ‘How do you live in New York without nature?’ — are you kidding? I’ve got it embedded. I see it every day.”