July 13, 2015Michael Boyd was already a respected collector of modern design when he bought and renovated Brutalist architect Paul Rudolph’s New York townhouse, which proved a watershed moment in his career (photo by Anaïs & Dax). Top: Farmshop, a holistic Marin County grocery store by L.A. design firm Commune, features pieces from the Boyd-designed PLANEfurniture line (photo by Mariko Reed).

Michael Boyd could be the poster child for the idea that if you build your own dreams, someone else will hire you to build theirs. Boyd was working as a music composer for advertising, television and film, living happily in San Francisco with his wife, Gabrielle Doré, and their two sons, when, in 2000, he and his family relocated to Manhattan. They had purchased the iconic Beekman Place townhouse of Paul Rudolph, which was in desperate need of renovation following the modernist architect’s death in 1997.

At the time, Boyd was already known among design aficionados as a serious collector, thanks to a 1998 exhibition at SFMOMA that featured more than 100 pieces from his collection of furniture and objects by such visionary 20th-century designers as Gerrit Rietveld, Charles Eames, Frank Lloyd Wright, Carlo Mollino and Jean Prouvé, all assembled over nearly two decades.

Although Boyd had already obtained building knowledge via some half-dozen modernist restorations throughout the Bay Area — both for friends and for his own personal projects — the renovation of the Rudolph house represented a new challenge, in both scale and complexity. Inspired purely by a sense of adventure, the move marked a turning point in Boyd’s life: This longtime design enthusiast would morph into a professional preservationist and, ultimately, a designer of interiors, landscapes and furniture — hired by others to do what was initially a highly personal labor of love.

“The Rudolph house was a great laboratory for hands-on experience,” Boyd says, explaining that his family moved into the house as he concurrently began its meticulous restoration. Armed with a dose of courage and, he says, stacks of “books on the history, practice, and restoration of modernist architecture,” he dove right in. “Deep restoration is a full commitment,” he explains. “It’s not something to consider lightly — it’s like a marriage.”

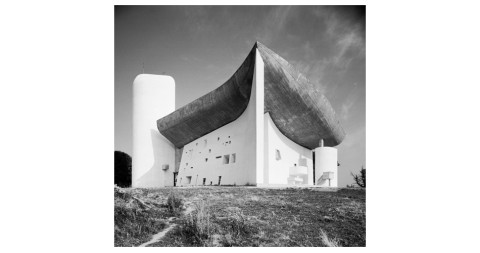

Boyd’s gamble paid off. His work on the property was widely admired, featured glowingly in the New York Times and many international design publications, and its success lead him to his next project: a major renovation of Oscar Niemeyer’s white-brick-and-glass Strick House, in Santa Monica, which Boyd and his wife purchased as their next home the day they sold the Rudolph property. The famed Brazilian architect’s only North American residential commission had been on the verge of demolition by a local developer, despite the outcry of local preservationists.

“We really did our due diligence,” Boyd says, explaining that the renovation required fastidious attention to detail — they replaced wall-to-wall carpet and linoleum floors in the living, dining and kitchen areas with palmwood, for example, in homage to the house’s Brazilian lineage. “We contacted Niemeyer’s office in Brazil, he was still alive at the time, and worked with them closely.”

“Deep restoration is a full commitment. It’s not something to consider lightly — it’s like a marriage.”

Situated overlooking a golf course and the Santa Monica Mountains, the house boasts impressively lofty ceilings in the public spaces: The living room’s 14-foot-high walls of glass are the ideal expression of indoor-outdoor California living. There were no plantings at all on the property, as the developer had destroyed them in anticipation of demolition — so Boyd turned his attention to the grounds as well, designing the tropical garden in a manner inspired by the work of Roberto Burle Marx, a frequent Niemeyer collaborator.

Once the Strick House and the story of Boyd’s singular “art de vivre” appeared in the pages of Architectural Digest, it wasn’t long before he began receiving calls to work for others. To date, Boyd has restored more than a dozen landmark properties throughout California, including houses by modernist architects Craig Ellwood, Richard Neutra, John Lautner and A. Quincy Jones, garnering a well-deserved reputation as a premier modernism-preservation specialist.

Another Commune project, the American Trade Hotel, in Panama City, Panama, features a suite of mint-green Plank chairs from Boyd’s PLANKseries, for which he cites Rudolph Schindler and Gerrit Rietveld as influences. Photo by Spencer Lowell

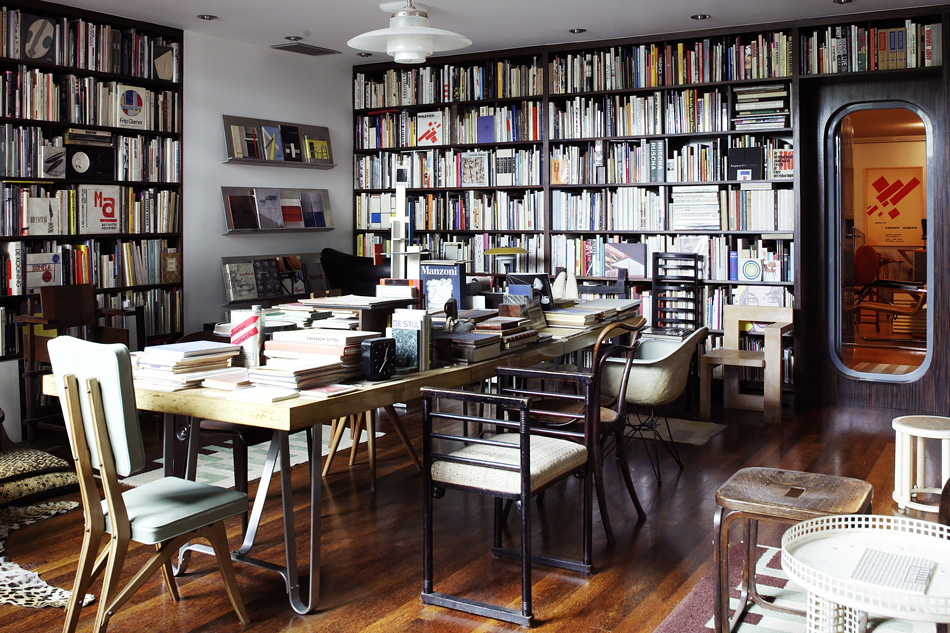

The Niemeyer house remains the Boyds’ primary residence and is furnished with their extensive collection of modernist furniture, from Mallet Stevens to Prouvé to designs by Niemeyer himself. It also houses the family’s vast library of design books, which includes some 10,000 volumes — and counting. “We live in an environment that is a whole,” says Doré. “From the house to the furniture, it’s all art to us.”

“The dictum ‘Do something you love and fortune will follow’ has certainly been true for us,” Boyd says. “Our return on the investment we’ve made in the restoration of our own houses and the building of our collection has far outstripped the stock market.”

Boyd was raised in Berkeley, where his father was a professor of English and philosophy at the University of California. His mother, also an English professor, collected antiques as a hobby. “She dragged me around to flea markets,” says Boyd, who reckons his love for the modernist aesthetic was born out of a reaction against the froufrou Victoriana that was the taste of his mother and her friends. “I think what makes modernism so powerful and lasting is that it was a movement that reset the stage for living in today’s world, ” he explains.

Boyd bought his first piece of modernist design, an Eames chair, at the age of 18. After studying painting, music and linguistics at UC Berkeley he launched a career as a commercial composer, working for the likes of Nike, Levi’s and Coca-Cola and producing scores for both film and television. In 1989, he met Doré, who was producing commercials for a San Francisco ad agency. “We feel like between the two of us we make up one competent adult,” jokes Boyd, who deems himself a dreamer and his spouse a pragmatist. “She’s got her feet on the ground.”

In Richard Neutra‘s restored 1949 Wirin House, in the Los Feliz neighborhood of L.A., Boyd emphasized the space’s clean lines with an N1 rug of his own design. Photo by Hans Eckardt

Featuring pieces made between 1900 and 1970, with a focus on what he calls “progressive design, mostly by architects,” Boyd’s collection includes works by early-20th-century Viennese creators, such as Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos; Scandinavians, such as Hans Wegner, Arne Jacobsen and Alvar Aalto; post-war Americans, including Eames and George Nelson; and such Italians as Mollino and Giò Ponti. “And don’t forget the French,” adds Boyd, “from Pierre Chareau to René Herbst to Pierre Paulin.”

“I consider it an archive of ideas,” Boyd says of the collection he houses between his residence and his showroom-studio in L.A., as well as in his by-appointment showroom-studio in San Francisco. “It’s a kind of laboratory for studying what makes great design great.” Having trained his eye in such a manner, in 2012 Boyd launched PLANEfurniture, a collection of his own creations. The pieces were unveiled at Edward Cella Art + Architecure, in L.A., in a show titled “types + prototypes.”

“These pieces are more surrealist, anthropomorphic, expressionist,” says Boyd of his most recent Custom Shop Series, which debuted in 2014 at San Francisco’s Hedge Gallery. “I tried to keep the designs super-graphic.” Photo by Patrik Argast, courtesy of Hedge Gallery

“I find it fascinating to see how Michael’s intimate knowledge as a collector has influenced his work as a designer,” says Cella. “Each piece in his collection is an opportunity for him to distill his thinking about certain forms but also advance each of them to address contemporary lifestyles, materials and manufacturing.”

For his part, Boyd explains that his goal is “to take European modernism aesthetics and re-present them in a California-casual style. I think of them as unfussy, user-friendly pieces. Most of them can live both inside or outside.”

The PLANEfurniture collection is composed of five series: The PLANKseries is “anything planar,” he explains, citing Rudolph Schindler and Rietveld as influences. The RODseries clearly owes a debt to Walter Lamb, with its powder-coated armatures and seats made of cord. For the WEDGEseries, he names Neutra and Pierre Jeanneret as inspiration. And the work of Donald Judd influences the BLOCKseries.

The fifth series — his Custom Shop Series — was unveiled in a 2014 exhibition at San Francisco’s Hedge Gallery. This grouping of designs explores freer forms like those of Calder, Arp and Noguchi. “These pieces are more surrealist, anthropomorphic, expressionist,” says Boyd, describing their handcrafted quality. “If you look, there’s a through-line in everything I do. I tried to keep the designs super graphic; I tried to keep in mind: composition, abbreviation, paring things down.”

Pictured here as part of a photo shoot for Commune-designed tiles, Boyd’s Bat chair combines a patinated-bronze frame with a seat and seat-back of striped zebra wood. Photo by Spencer Lowell

Many examples of Boyd’s past work, as well as new furniture pieces, and a series of rugs he recently designed for Christopher Farr, can be seen this fall when legendary L.A. antiquaire Joel Chen, of JF Chen, presents them in a show titled “FOREVER PAST EVER PRESENT.”

Beyond these exhibitions, Boyd’s furniture can be seen installed in multiple projects by Commune, arguably Los Angeles’s coolest design firm. He has closely collaborated on furniture for several of their projects, from the Ace hotel in downtown L.A. to the American Trade Hotel, in Panama City, Panama, and the holistic grocery and restaurant Farmshop, in the Marin Country Mart in Larkspur, California.

Boyd is currently writing a book for Rizzoli on the California modernist architect Craig Ellwood and producing a documentary film with Ellwood’s daughter Erin Ellwood and director Maria Demopoulos. And as if his calendar weren’t already full, he has recently been commissioned to design and build a 6,000-square-foot modernist villa in Malibu. (He partners in architecture with designer Laurel Broughton; their new firm is called Boyd + Broughton.)

“Building from the ground up is tremendously exciting,” he says of the latest in his long list of creative ventures. “It’s all composition. That’s where it starts and ends; I started with music, but now I’m composing furniture, gardens and buildings — it’s really all the same language.”

Michael Boyd’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs