October 3, 2021Jewelry designer Matthew Harris has one simple rule when it comes to deciding which pieces are going to make it into a new collection: “If it’s going to sit in the jewelry box, then it’s gone,” he says. “I want it to be wearable and worn daily.”

So Harris — whose nickname, Mateo, is also the name of his company — has crafted a collection of pieces that range from easy-to-wear essentials like faceted gold huggie hoops to more dramatic, maybe-not-quite-everyday items like graduated pearl-and-diamond hoops with pearl drops.

“I design for my generation,” says Harris, who remembers his peers’ buying low-quality, inexpensive costume jewelry at fast-fashion retailers and was inspired to create pieces that were elevated, yet attainable. Or, as he puts it, “I wanted people to be able to buy great jewelry without breaking the bank.”

Born and raised in Jamaica, Harris references his homeland through the materials he uses, but subtly. (“People expect me to make jewelry out of shells because I’m Jamaican,” he deadpans.) The colors of the country’s flag are represented in the yellow gold, malachite and onyx that figure so prominently in his designs. He also favors turquoise, which he says represents the Caribbean Sea. Another strong influence in his life is his mother, a seamstress, who is honored in his gold scissor necklace.

Harris did not receive any formal training in designing or making jewelry. He learned his craft by reading books, watching videos and hanging out in Manhattan’s jewelry district until a bench jeweler, an older Russian gentleman whom he now calls his “foster father of jewelry making,” finally agreed to teach him. The experience quite literally left a mark — so many marks, in fact, that his arms are now covered in tattoos to hide the scars he got from soldering and polishing jewelry.

Harris launched his business in 2009 with a men’s collection but pivoted to women’s jewelry in 2015. He had noticed a gap in the market: pearls. The gem happens to be his birthstone, and he wears it daily, but he knew it had a bit of an old-lady reputation. “No one was designing with pearls at the time,” he says, “so I wanted to make them fresh and cool again.” His creations include the Duality drop earrings, which pair small round pearls with big baroque ones, and the Orbit ring — inspired by a Wassily Kandinsky painting — in which a pearl seems to float on a gold circle over a diamond band. Then there are his Curve earrings, composed of graduated pearls that gently wrap around a bar of pavé diamonds finished off with a drop pearl. “They look good on everyone, which is really important to me,” Harris says of the earrings, which were included in a recent Sotheby’s sale featuring Black jewelry designers.

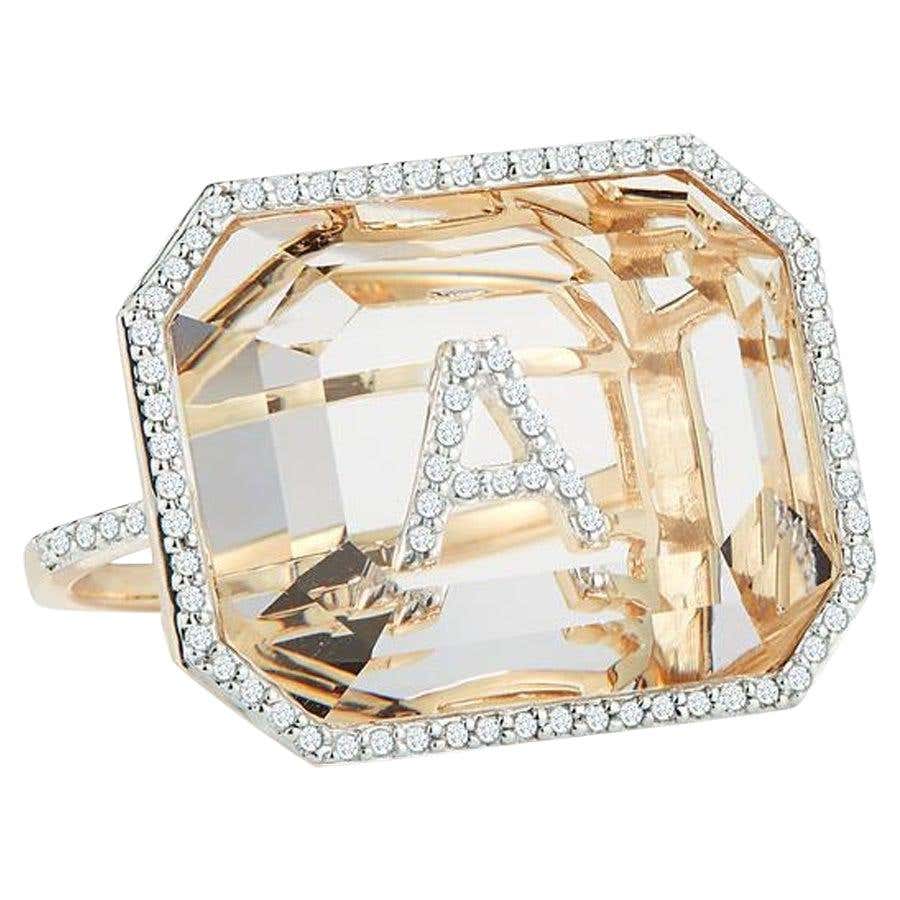

“Being self-taught is a blessing,” he says. It meant he wasn’t constrained by the knowledge of the so-called “right” way to do things, or whether something was considered impossible. He has also found beauty in what at first seemed like a mistake. Take his Secret Initial collection of rings and pendants, in which a pavé diamond letter is set within rock crystal as if floating inside it. The initial was supposed to be on the outside of the stone, but what was an error proved a revelation, and now Harris considers the collection a favorite, regarding the pieces as future heirlooms. They also have modern-day appeal: Andra Day wore a pair of Secret Initial rings on a recent cover of InStyle magazine.

Mateo jewelry has garnered plenty of media attention and amassed plenty of celebrity fans, including Zendaya, Taylor Swift, Cynthia Erivo and two of perhaps the most influential figures in fashion: Rihanna and Michelle Obama. Still, Harris is most excited when he sees everyday women wearing his pieces. “I’m always humbled and shocked that people like my work,” he says. And whether it’s on a red carpet or a Zoom call, his streamlined, elegant pieces have the same effect —imbuing the wearer with an aura of effortless cool.

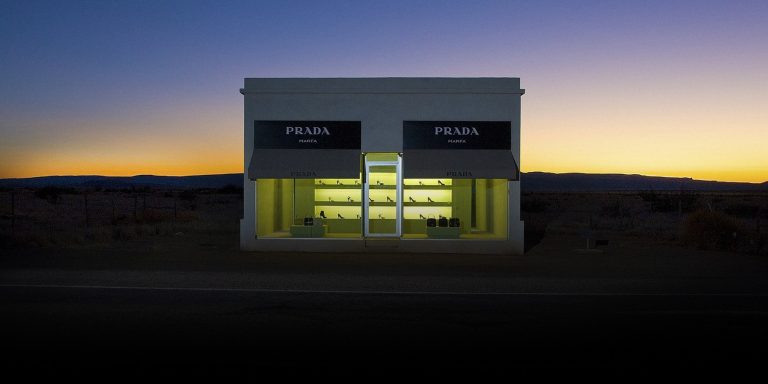

The phrase “effortless cool” could also be used to describe Harris’s Houston home, but that would diminish the work he has put into making it the serene, minimalist haven it is. Of course, serene and minimalist are adjectives not often applied to the interior design aesthetic of Houston — or Texas in general. And, according to Harris, the house was “very Texas,” when he first saw it, in 2020, after moving to town that July. (He had recently returned to the States from Luxembourg, and Houston was closer to Jamaica than his apartments in New York and Los Angeles.) So, he stripped away the excesses, like the gas fireplace and wet bars, to distill the space to its essence. “It’s night and day from when I bought it,” he says. “I made it fresh and light and simple.”

Once the home was a blank slate — all clean lines and white walls — he set about furnishing it with pieces that resonated with him. “The beauty of not being trained in jewelry or interior design is that I buy what I like,” Harris says. That includes mid-century items, but also contemporary pieces like Faye Toogood’s Roly-Poly chairs — he has a white version in his bedroom and a black pair in his office. Another key acquisition was a pair of Terje Ekstrom’s sculptural Ekstrem lounge chairs, which he discovered on 1stDibs a few years ago. “When they arrived, I was literally in tears, because I’ve been needing and craving them for so long,” he says.

Before the pandemic, Harris had neither the time nor the inclination to invest in his personal space, but spending more time there has changed that. “It’s been really nice to cultivate a home,” he says, adding, “It whispers tranquility and peace.” And, importantly, it has fueled his creativity: “Most of my inspiration is in the house.”