March 13, 2017Before establishing his firm, Marshall Watson studied theater design, acted in a soap opera and did scenic paintings (portrait by Mark Bradley Miller). Top: For the living room of this home in Newport Beach, California, Watson designed the diamond-patterned carpet, which draws the eye to the Frank Gehry cardboard chairs. On the mantel are a pair of Alberto Giacometti figures and a Pablo Picasso ink drawing. Photo by Lisa Romerein

As any good thespian knows, a believable performance relies on the actor’s complete fidelity to his or her character. It’s a lesson interior designer Marshall Watson understands more intimately than most. “While I have consistently been someone with artistic impulses,” he writes in his new monograph (coauthored with Marc Kristal) The Art of Elegance: Classic Interiors (Rizzoli), “they went in a variety of directions before I arrived at interior design.”

Watson’s circuitous route to his 30-year interior design career, we discover, led him first through a short-lived stab at being a fine painter, then into careers in theatrical design and acting. As a theatrical designer, Watson says, he learned that “you don’t design a Shakespeare play like you’re going to design a Neil Simon comedy.” And in both theatrical design and acting, he adds, “the interpretation of the script is always important. I like to see the world through characters.”

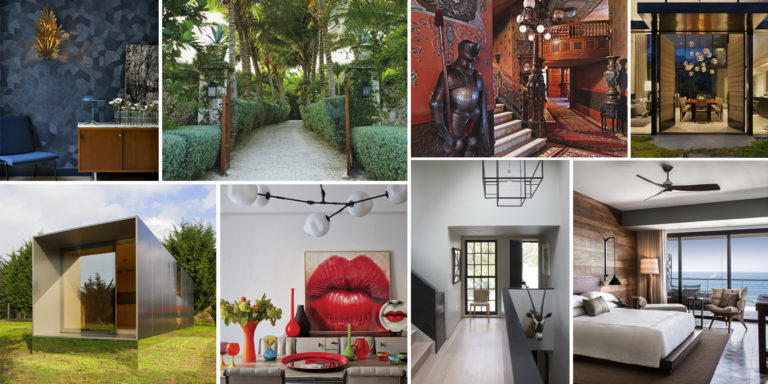

This is one reason Watson’s projects look so distinctly different from one another; each is a unique narrative (or “script”) seen through the eyes of his client, then visually translated using Watson’s passion for intensive research into the architectural and decorative styles necessary to tell that story compellingly. The most consistent thread, he argues in the book, is that “in all ways, I embrace the principles that transform a series of rooms into the true definition of elegance: Warmth. Light. Peace. Balance. Proportion. Livability.”

While one might quibble with specific elements of Watson’s definition — even an exceedingly formal room that appears unlivable can be indisputably elegant — there is no question that his interiors display these elements in abundance. A 1930s California Mediterranean home and another in the state’s northern wine country are redolent with the rustic warmth of wood, while organic textures and casual linens make a potentially overly grand Naples, Florida, home more inviting. The inventive palette of soft colors in a New York apartment makes the most of Gramercy Park’s available light, and a compound in Värmdö, Stockholm, possesses the contemplative serenity and quiet stillness of an Ingmar Bergman film. In all of these, there is not a single piece of furniture or lighting that feels too big or too small.

A shuttered partial wall separates the living room from the entryway in Watson’s East Hampton, New York, home. The Italian starburst mirror reflects the sea. Photo by Luke White

Watson, the son of an insurance broker and his philanthropist wife, grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, in “a beautiful French Norman Tudor house” surrounded by aesthetes. (And athletes: Older brother Tom is a PGA legend.) The family was populated with avid gardeners, including an uncle who was also a landscape painter. An aunt, he tells Introspective, “had tremendous style and always hired the youngest decorator in town because she liked new ideas. Her house had tortoiseshell walls, deep-olive-green sofas, large Chinese screens, Tibetan carvings and Jacobean furniture.”

These influences led him to Stanford University, where he earned his bachelor of arts in 1975, with an emphasis in art and design. To help pay for his education, he worked on the side as a model and actor. Discovering after graduation that the life of a painter was too solitary, he proceeded to Brandeis, outside of Boston, “for one very influential year” of theater design studies, and decided to pursue a career in the field. So he headed back to California in 1978 and enrolled in the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. Before long, Watson was acting and, in 1981, earned his master’s degree in the subject. “I was spotted by an agent and came to New York to be on As the World Turns,” he recalls. He remained on the soap opera from 1982 to ’83, also doing regional theater, off-Broadway and Broadway.

“Then I took a hard look at myself,” Watson says. “I had given myself seven years [to make it in the theatrical profession], and my love of design was reasserting itself.” So in 1984, Watson returned to school, enrolling at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. He made money doing decorative painting for other designers on weekends and also worked with designers Gary Crain and Nancy Klassen. Eventually, some of those clients began approaching him independently about small projects. “It went from built-ins and kitchens to paneled rooms,” he recalls. In 1987, he started his own firm.

Watson now employs eight people and handles 15 projects simultaneously — six of them, on average, what he calls “major.” He and his husband, Paul Sparks, a producer he met 35 years ago, share an apartment on New York’s Upper West Side and a New England–style shingle home in East Hampton designed by Watson himself. Since 1997, in addition to his interiors business, he has designed three furniture collections — about 70 pieces in all — for Edward Ferrell + Lewis Mittman, which, he says proudly, have been the trade showroom’s top-selling lines. He is currently at work on about 20 pieces for a fourth collection. In fall of last year, Watson released a line of outdoor rugs through Doris Leslie Blau. And then, of course, there’s The Art of Elegance, which has just been published.

“I introduced highly unusual plaster sconces, in the shape of floating floor lamps, which seem to emerge from the walls,” Watson writes of the Newport Beach home in The Art of Elegance. Photo by Lisa Romerein

As evidenced in the monograph, it’s most important to Watson that he conveys what he describes as “an uplifting sense of elegance. I want environments to be inspiring. And I believe in warmth, even if it’s all white.” A Southern California residence based on a design scribbled on a cocktail napkin by famed Mexican architect Luis Barragán in the 1960s is a case in point. Although Watson washed the entire house in white (as in Barragán’s legendary San Cristóbal stables, the walls had been painted in many saturated colors), it nevertheless exudes warmth through such details as the quilting of the dining room’s white leather chairs, burnished gold accents and the sensual curves of both a spiral stair and Andrée Putman’s iconic Crescent Moon sofa.

“I don’t disagree with something being exciting to look at,” Watson says, adding, however, that balance demands that it also be “comfortably gracious, coherent and appropriate to the environment.” In his East Hampton home, for instance, the living room’s sunburst mirror is spectacular in both proportion and presence. Yet it fails to steal the show amid an equally exquisite supporting cast: a Moroccan bone-inlay coffee table and a gilded clock above a mantel that sports dentil moldings, carved garlands and a Delft tile surround.

Designing this home, Watson writes, taught him that “[y]our nest isn’t a commodity, or a real estate venture. It’s home — and if that’s what drives all your decisions, really, you can’t go wrong.” It should be, in other words, perfectly in character with the actors who live its narrative.

Marshall Watson’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore