September 12, 2021Marlene Wetherell lives and breathes (and sells) chic. You can see her commitment to the aesthetic in the pieces on offer in her eponymous store, where “chic” means timeless, or what she calls “wearable,” fashion. “We try to stay away from looking vintage, like you came out of The Great Gatsby,” she explains.

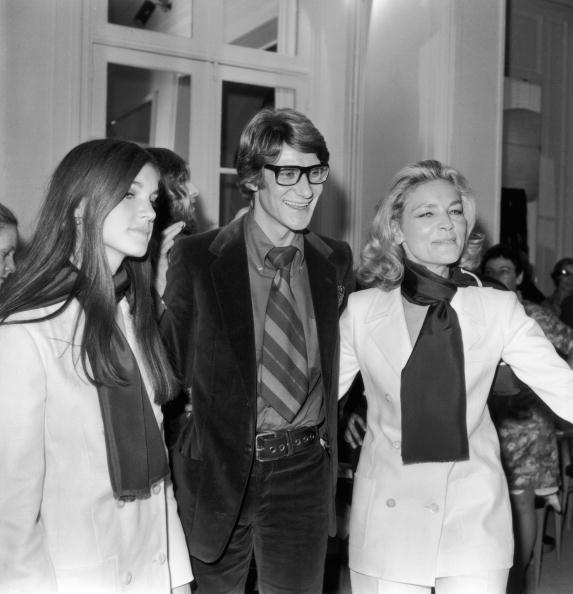

You can see it in her favorite designer, Yves Saint Laurent, who “was able to pair the classic with opulence,” she says. And you can see it in the woman herself, who exudes a timeless urbane style even during a late-afternoon Sunday Zoom call.

It’s interesting, then, to learn that her life in fashion grew out of her love of traditional early-American textiles and quilts, which she started collecting and selling to dealers in the 1980s. Eventually, she opened a shop on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where she added Edwardian garments, 1920s beaded dresses and calico-print Amish prairie dresses to her inventory. At decade’s end, she closed the shop and began working as an editorial stylist. By that time “too old to wear prairie dresses,” she says, she began hunting for “sophisticated designers like Saint Laurent, Givenchy and Norell” in the flea markets and thrift shops that proliferated throughout the city in the early 1990s.

Back then, she pored over magazines and fashion-history books to master the foundations of modern style. She was introduced to early examples of wide-leg trousers through the work of Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who photographed fashionable women of the 1920s on the French Riviera. And she was exposed to the timeless bias-cut dresses of Vionnet and Madame Grès through the 1930s images of Vogue photographer George Hoyningen-Huene.

Today, she says, “I like to think of the store as a laboratory of ideas.” But don’t picture stark white walls and lab coats. Instead, her showroom, in the Nomad neighborhood of Manhattan, is a lively space with fuchsia walls and hundreds of garments designed by the greats of European and American fashion, including Yves Saint Laurent (of course), Givenchy, Balenciaga, Geoffrey Beene, Norman Norell and Bonnie Cashin.

Her store, with its carefully curated collection, is a regular stop for celebrity clients and fashion design teams doing research. When asked to name names, Wetherell demurs. “It’s just not who I am,” she says, preferring to keep the shop “discreet and under the radar.” In this age of tell-all social media, hers is an uncommon sensibility, reflecting an enduring sophistication. As Yves Saint Laurent once said, “Without elegance of the heart, there is no elegance.” How very chic, indeed.

Here, Wetherell speaks with Introspective about vintage fashions in modern wardrobes, the wonders of Yves Saint Laurent and how American designers created an entirely new perspective on fashion.

How would you describe the style of vintage you sell in your store?

We’re not into trends, but we’re modern, and our clothes fit into what’s happening now. For example, the nineteen-seventies blazers that women love because of the cut — they have a certain closeness to the body, the armholes are cut in a certain way that provides a slimming silhouette — those always sell immediately, whether heavy-cotton Yves Saint Laurents or wool tweeds. Then there are the pretty silk blouses that have a bit of a romantic flavor with the lavallières [pussy bows], the pretty prints. You don’t see those extraordinary silks anymore.

You’ve said Yves Saint Laurent is your favorite designer. What makes him a standout?

He really loved women. As a designer, he was always about the woman and not so much about the clothes. That’s why I appreciate him. With Balenciaga, it wasn’t about the woman — although, of course, he was a master. Even with Dior, it was the construction, the jacket. To me, Saint Laurent was the ultimate man who not only loved women but made them chic.

What designs do you consider iconic Saint Laurent?

Of course, there was the tuxedo, Le Smoking. Putting a woman in a masculine style and adding one romantic touch, like a sheer chiffon blouse under the tuxedo jacket — there was a sexiness in that masculine-feminine combination.

He also had a folkloric period, his Chinese and Russian collections. And there was the forties influence of the 1971 Scandal collection, which [earned that name because it] romanticized the occupation of Paris during World War II. For a lot of French people, it was not a romantic time, and they did not want to be reminded of it. So that became a little bit of a political issue.

And then, of course, there was the safari look. Not just the Saharienne, that famous tunic worn by Veruschka in 1968 [shot by Franco Rubartelli for Vogue]. He did safari jackets and skirts and khakis in these wonderful patterns. So well constructed.

Have you seen an increase in the popularity of any particular designer?

Recently, we’ve seen more of an interest in Christian Lacroix — his clothes and his jewelry. He’s another designer who used a lot of fantasy. His debut couture collection, in 1987, and second couture collection, for Spring 1988, were inspired by his birthplace, Arles, and the eighteenth-century costumes of Provence. He also designed a lot for the opera. His designs can be very playful.

Is there an under-the-radar fashion designer whom you think deserves more attention?

Isabel Toledo [who died in 2019 at the age of 59] was a master. Her silhouettes were very feminine, and her clothes were so beautifully constructed that you could practically wear them inside out. Her partnership with her husband, the illustrator Ruben Toledo, was extraordinary. I had the good fortune of meeting them once in their studio in the Flatiron district. They were the most lovely, unpretentious people, who were very committed to their craft.

In your opinion, who were some of the other greats of American fashion?

There are too many to mention! Some of my favorites include Geoffrey Beene, who had an endless imagination, full of humor and whimsy. He used gray flannel, wool jersey and tweeds in formal clothes and created a very daring sequined football jersey gown. Norman Norell’s designs had a timeless elegance and easy chic — both Marilyn Monroe and Lauren Bacall were fans.

Claire McCardell invented American fashion. She always considered how American women would feel and function in her clothes. And Halston’s approach was modern and glamorous, yet simple. He was known for his use of Ultrasuede, cashmere knit in evening wear and tie-dye on silk charmeuse. He influenced many designers in generations to come.

In general, what distinguishes American fashion is that its designers did not look to Paris. Instead, they thought about the needs of American women, how they moved and how they lived their lives.

What item do you love too much to sell?

I might keep something for a little while because it fits into my lifestyle — like some Saint Laurent jewelry. But eventually, I end up selling it. I’m in business!

Is there anything that you regret having sold?

I wish I’d held onto a Karl Lagerfeld for Chloé chemise dress a little longer. It had trompe l’oeil beading that looked like draped fabric. But it sold immediately to an accomplished artist who often uses trompe l’oeil techniques in her paintings — the perfect owner.