July 28, 2024It was the unlikeliest of beginnings for a company that became one of the world’s most distinguished in any field, renowned for the utmost in technical innovation, design excellence and craftsmanship.

Louis Poulsen’s dazzling array of light fixtures, many designed a century ago and still in production, have found their way into innumerable homes, offices and commercial buildings around the globe. The Danish maker’s proud history is documented, with rare archival photos, in Louis Poulsen: First House of Light by TF Chan, published by Phaidon this summer to coincide with the company’s 150th anniversary.

The business Ludvig Raymond Poulsen founded in 1874, however, wasn’t a lighting company at all. Electrification had not yet come to Denmark; candles and kerosene lamps were the order of the day. The young man began as a wine importer, but the field was crowded, and his enterprise struggled. In the early 1890s, when electrical power arrived, he opened a shop in Copenhagen selling carbon-arc lamps, an early form of electric lighting, along with scissors, plumbing supplies and other utilitarian items.

In 1896, Ludvig was joined by his nephew Louis Poulsen, who moved the company’s headquarters to Nyhavn, Copenhagen’s colorful port. Ludvig died in 1906, and Louis sold half the business to forward-thinking Sophus Kastrup-Olsen, retiring in 1917 to become a gentleman farmer. But the name Louis Poulsen & Co. remained.

In the early 1920s, a polymath and newly minted architect, Poul Henningsen, came to Kastrup-Olsen with a group of drawings for light fixtures that became the basis for the company’s contribution to the Danish pavilion at the seminal 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. The importance of that meeting can hardly be overstated. Henningsen’s collaboration with Louis Poulsen lasted decades, from the Art Deco era through the mid-20th century and into the age of Pop.

“Henningsen was also a prolific journalist and an outspoken champion of radical ideas, for whom design and social advocacy went hand in hand,” writes Chan, a longtime editor of Wallpaper* magazine. “He saw in Kastrup-Olsen a kindred spirit.” Henningsen described his collaborator more colorfully, as “a man as crazy as me.” Together, they began to shape Poulsen into the institution we know today. Here, we look at some of the company’s best and most enduring designs.

The PH System

In those early days and throughout his long career, Henningsen was fascinated with the possibilities of using curved metal shades to sculpt and shape artificial light. Among his designs for the Paris expo was the six-shaded Paris lamp, whose layered plates of silver directed light from a central source in ways both beautiful and functional, along with a globe-shaped pendant with tiers of horizontal shades, a progenitor of the 1962 Contrast lamp and today’s Snowball.

Over the years, the Paris lamp was refined and produced in aluminum versions with three, four or five shades. The variations were offered in table, floor and pendant styles. Collectively dubbed the PH system, they became some of the world’s most popular lighting designs.

It’s said that one in five Danish families owns a PH 5 lamp — the version with three downward-curving shades, a short cylindrical uplight at the top and a downlight at the bottom. The PH 5 remains a top seller to this day; it comes in a range of sizes and colors (19 at last count) and still has a silhouette very similar to that of Henningsen’s 1920s concept. It’s a design so pure that, however refreshed or tweaked, it refuses to date and simply cannot be bested.

Public Projects

The Louis Poulsen company has undertaken many projects for the public good, all comprehensively chronicled and illustrated in the new book. As early as 1919, Henningsen created minimalist street lighting for the city of Copenhagen, which remained in place for half a century. He also conceived specialized blackout lamps for use during World War II.

Among his most-loved designs were rotating spiral-shaped lamps for the city’s Tivoli Gardens amusement park, dating from the 1940s. Alas, the motors in those famous lamps were easily jammed by random twigs from surrounding trees. They remained motionless for decades, until 2008, when Louis Poulsen produced new versions that replicated Henningsen’s originals but with more powerful motors. “These continue to mesmerize visitors today,” Chan writes.

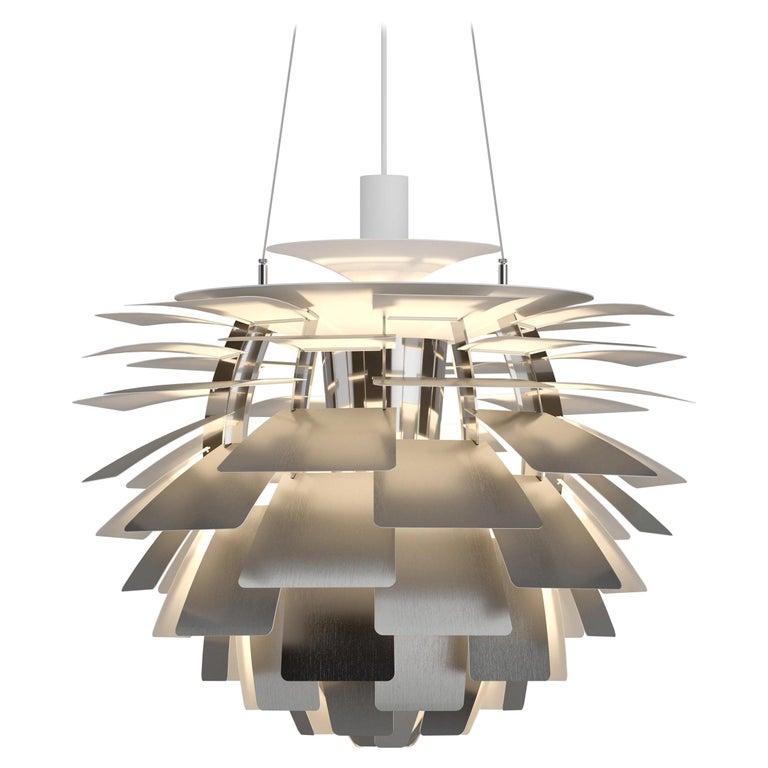

The Artichoke Lamp

Henningsen’s crowning aesthetic achievement, and a staple of design museums worldwide, the PH Artichoke debuted in 1958 and has been in production ever since. Created for a new International Style restaurant in Copenhagen’s harbor, the lamp met all the requirements set out by the building’s architects, including that it be “festive and emanate a warm glow.” With 12 staggered layers of six metal leaves, each layer shaped and bent differently to properly direct the light, the Artichoke is one of Louis Poulsen’s best-known designs, available today in four sizes and eight colors.

The VL Radiohus 45

The spherical pendant fixture is a basic archetype that invites experimentation, and Louis Poulsen has produced numerous highly creative iterations of the form. Architect Vilhelm Lauritzen’s VL45 Radiohus, a pendant with an opal-glass shade mouth-blown into a subtly compressed capsule shape, was designed in the 1930s and reintroduced in 2016 with great success.

The AJ Lamp

In 1957, Arne Jacobsen, Denmark’s most influential architect and designer of the iconic Ant and Egg chairs, invented the rakish AJ lamp for Louis Poulsen. With its conical black shade on an oblique angle, like an insouciant little bird, it has for decades been a stylish workhorse as a task lamp, floor lamp or sconce.

The Panthella, Moon and Flowerpot

By the 1960s, the company was collaborating with Pop luminary Verner Panton, who helped usher in a new era of fluid, dynamic design. His graceful 1971 Panthella lamp, a semicircular shade on a slender pedestal base, is still in production in table and floor versions.

Panton’s 1961 Moon pendant, an arrangement of adjustable aluminum rings on a vertical axis, and his 1967 Flowerpot pendant — two nested hemispherical shades, often in bright colors, which became an emblem of hippiedom and sold a quarter million units in the first year after its release — are no longer in production but are beloved by aficionados and quickly scooped up whenever they appear on the secondary market.

Contemporary Classics

Poulsen is still an international design powerhouse today. Its progressive management seeks out contemporary talents to create lighting for the current era that reflects the design ethos the company has maintained all along: pared-down simplicity, impeccable engineering and — of great importance since Henningsen’s day — soft, pleasant, glare-free light conducive to human well-being.

Notable recent additions to the catalogue include Japanese designer Shoichi Uchiyama’s 2003 Enigma pendant, which builds on Henningsen’s lighting concepts; Øivind Slaatto’s 2015 Patera, a woven-acrylic sphere composed of diamond-shaped cells; Clara von Zweigbergk’s 2016 Cirque pendant, inspired by the Moorish-style onion domes at Tivoli Gardens; the 2016 NJP floor, wall and mini lamps by the Japanese studio nendo, modern takes on Arne Jacobsen’s AJ series; the 2017 Above pendant, a cone of powder-coated aluminum by Mads Odegård, radically minimalist but not at all severe; and Olafur Eliasson’s ingenious 2019 OE Quasi, a multisided polygon of transparent plastic floating within an aluminum frame. Anne Boysen’s Moonsetter, a square chrome-plated frame in which an illuminated disc rotates, emerged out of a 2020 entry for the TV competition Denmark’s Next Classic, and it seems set to become one.

In 2023 Poulsen tapped Breanna Box and Peter Dupont, the young couple behind New York–based brand Home in Heven, to update well-known designs including the PH 5 and VL45 Radiohus. The result was a collection of whimsical one-off pendant and table lamps in hand-blown glass that was auctioned on 1stDibs earlier this year.

Louis Poulsen is one of the world’s cultural treasures, the lighting equivalent of Venini glass. While some of its output, like the oversize OE Quasi and Artichoke lamps, costs well into five figures, other offerings, like Panton’s small Panthella lamps, are accessibly priced at around $400, harking back to the firm’s original goal of creating good design for the many. Adherence to such founding principles has stood the company in good stead for more than a century and kept the venerable maker light years ahead of its time.