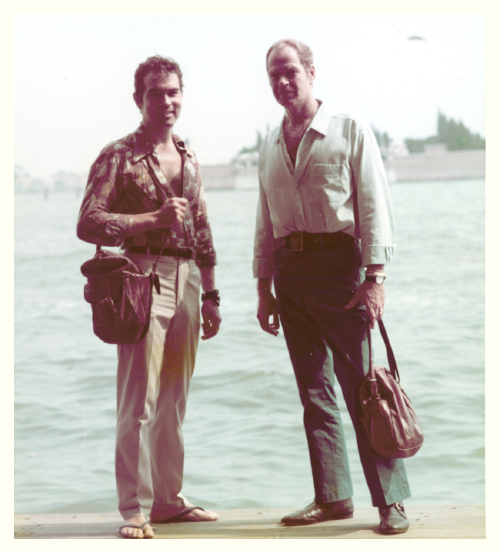

June 1, 2022When Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman first invited the public to see their art collection in their Soho loft, in 1969, they could have been fined, or even arrested. Much of the work was blatantly homoerotic, and obscenity laws were still being used to censor and control New York City’s gay and lesbian population. Hundreds more people than they’d anticipated arrived to see the show, and it became clear that the city needed such an art space.

A month later, they found themselves at the frontier of a new era, as the Stonewall riots ignited the gay liberation movement. But the art world remained largely squeamish about homosexuality and continued to reject the artists whom Leslie and Lohman knew and collected.

So, they opened a gallery in a basement on Prince Street to display their continuously growing collection of work by gay artists, including Neel Bate, George Platt Lynes, Jack Shear and Andy Warhol. (The couple was also instrumental in transforming Soho from a commercial to a residential neighborhood and preserving many of its historical cast-iron buildings.)

In 1990, they established the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation as a nonprofit organization — a hard fought achievement, considering there was no precedent for a foundation with “Gay” in its name — and in 2006, the gallery moved to a storefront at 26 Wooster Street, where it resides to this day. That space, then called the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art and now simply the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, is still the only dedicated LGBTQ+ art museum in the world.

This month, 1stDibs is supporting its efforts through sales of art, jewelry, fashion and furniture from our Pride Collection.

Times have changed since Leslie, a real estate investor, and Lohman, an interior designer, began carving out a niche for gay artists. For one, the art world now has room at the table for LBGTQ+ creators as well as a far more expansive and inclusive understanding of queerness. This evolution has enabled the museum to increase its visibility and impact and to establish itself as a rigorous and ambitious contemporary-art institution while also providing a space for those on the margins.

Over the past few years, the institution has seen a number of firsts. In 2016, it earned its museum accreditation and hired its first executive director, Gonzalo Casals (who went on to serve as commissioner of New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs).

It dropped “Gay and Lesbian” from its name in 2019 — a sign of the expansion of its mission to include queer and gender-fluid art and artists — and also hired its first chief curator, Stamatina Gregory. And last year, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art appointed its first female-identifying executive director, Alyssa Nitchun, who spent seven years at Creative Time, the producer of socially engaged, cutting-edge public art installations throughout New York City.

“On the one hand, the Leslie-Lohman is a place of experimentation, radicality, possibility and imagination,” says Nitchun. “But I also want it to be taken seriously as an institution.”

Given the increase in queer visibility and the fact that more LGBTQ+ artists are finding representation in the mainstream art world, some might wonder why we still need museums like the Leslie-Lohman.

“Yes, the art community has changed, and you’re seeing more LGBTQ artists in museum and gallery shows, but the Leslie-Lohman is purely for us,” says Dave Harper, executive director of the New York City AIDS Memorial. “It is willing to take risks outside the market, outside of what is commercially valuable, outside of art superstars.”

In that regard, the Leslie-Lohman is currently presenting the first U.S. exhibition of work by Lorenza Böttner, a transgender German performance artist, painter and dancer who lost both her arms in her youth and yet persevered creatively. She died from HIV-related causes in 1994.

“This is an artist who has never previously shown in the U.S., who has not been part of the art historical canon, who is not in collections yet represents this timely, expansive intersection and multiplicity of identities. And the work is really good,” says Nitchun. “It feels like a very specific kind of contribution that the Leslie-Lohman can do well.”

In recent years, the museum has also been exploring the intersections of different marginalized identities, including queerness, race and disability. Last year, for instance, it mounted the first comprehensive retrospective of the trailblazing Chicanx lesbian photographer Laura Aguilar, who was open about her struggles with mental illness.

“We’re doing the work to be a catalyst and rethink what it means to be a cultural institution that serves and engages all of these different intersections, and to say this is how we talk about ability and disability and transness and bring in communities throughout the whole of it,” says Aimée Chan-Lindquist, the museum’s director of external affairs.

“MoMA has these artists, but if there is a dick in one of them or an expression of sexuality, it’s not going up on the wall.”

In addition to bringing more rigor to the exhibitions program, Nitchun and her team (which includes several people in newly created roles, including director of engagement and inclusion J. Soto and Chan-Lindquist) have developed an acquisitions policy focused more on living artists and groups underrepresented in the collection.

As part of that strategy, they’ve spearheaded a new program called Interventions, which provides contemporary artists with grants to research and engage with works in the museum’s holdings. For the first Intervention, slated for winter 2023, the Honolulu-born, Los Angeles–based trans photographer, documentarian and performer Coyote Park (who has Korean, Yurok and European ancestry) has been restaging homoerotic work from the 1990s by artists such as Yiannis Nomikos and Li Ming Shun.

Last year’s acquisitions reflect the museum’s increasingly bold and ambitious approach to building its collection. Among them were works by Jonathan Lyndon Chase and Jeffrey Gibson — two names likely familiar to contemporary-art enthusiasts — along with a major piece by transgender artist Cassils.

Cassils’s installation consists of a glass box containing several hundred gallons of urine, set on a pedestal and accompanied by the vessels used to collect and store the fluid. The artist created the work in response to the Trump administration’s reversal of an Obama-era policy allowing public school students to use bathrooms that align with their gender identity. The work may present logistical challenges when it comes to presenting, storing and conserving it, but Nitchun is undeterred. “If the Leslie-Lohman isn’t a home for this piece, where is?” she asks.

“In terms of acquisitions and collections, we need to be that place — the place of if not here, then where?” adds Chan-Lindquist. That question has been a guiding principle of the museum since its inception. Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman clearly had an eye for art that happened not to belong anywhere else — the Soho apartment they shared is still covered with images that include penises. (Leslie is 88; Lohman died in 2010, at age 87.)

During the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, their collecting took on a greater sense of urgency and activism, as they rescued hundreds of works whose makers had died.

“They were constantly getting calls: ‘So-and-so has passed away, and the family is burning their art.’ That’s when the collecting really picked up,” Nitchun says. “Some might critique the museum for ossifying around a cis-white-gay-male culture. But on the other hand, you can also really understand that it was a refuge and sanctuary for a community and it coalesced for complex reasons.”

Over the years, the collection has grown to more than 30,000 objects, including pieces by artists well-known in LGBTQ+ circles, like Mariette Pathy Allen, Donna Gottschalk, Jimmy DeSana, Hugh Steers and Eric Rhein. But there are also plenty of blue-chip household names.

“We have Warhols and Mapplethorpes and Keith Harings, but ours are way more representative of our sexuality,” says Michael Manganiello, president of the museum’s board of trustees. “MoMA has these artists, but if there is a dick in one of them or an expression of sexuality, it’s not going up on the wall. Our lives are edited out of these museums. That’s why the Leslie-Lohman is so important.”

In 2019, Manginello announced a bequest to the museum of $500,000 and his collection of more than 150 objects, including artworks by Peter Berlin, Mark Morrisroe, Jack Pierson and Tyler Udall.

Nitchun and her team are also busy plying other fundraising avenues. Last year, they partnered with the city on a capital renovation project, which began under former executive director Casals and is just moving into the implementation phase. This will allow the museum to restore its historic facade and double its exhibition space. They’ve also received grants to overhaul things like the cataloguing and digitizing of the museum’s art collection and vast archives.

In addition to these projects and the 1stDibs collaboration, they are partnering with Gucci on a Pride Month Queer Icons conversation series and just received funding from the Ford Foundation for queer disability programming.

“There is a move toward a kind of a professional rigor in terms of what we want to achieve as a museum. It’s a kind of growing up,” says Nitchun. “We decided we want to be in it for the long term.”