September 10, 2014For many artists, taking down a show can be an unpleasant, almost funereal, task. But not so for Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick, who convened earlier this summer at New York’s Yancey Richardson gallery to gather the photographs, paintings and sculptures that depict the travails of their fictional Truppe Fledermaus, a ragtag group of eccentrically costumed performers dragging props and sets across a world on the verge of apocalypse. If the mood in the gallery was upbeat, it was because the show wasn’t really over — and it still isn’t. “We’re like a kind of traveling circus,” says Kahn, speaking as much about himself and Selesnick as about the Truppe.

Indeed, versions of Truppe Fledermaus will be seen in galleries in several cities over the next few years. First up is Atlanta’s Jackson Fine Art, where the show is on view from September 19 to November 5. Visitors will “question whether the narratives are fact or fiction, history or premonition,” says Jackson director Anna Walker Skillman. Either way, “the work addresses important social and environmental issues, forcing attention through its playful and imagined history.”

“There isn’t anyone else doing work like this,” adds Paul Kopeikin, director of the Kopeikin Gallery in L.A., who has shown Kahn & Selesnick since 1999. “The locations change, but their unique way of seeing the world always comes through.”

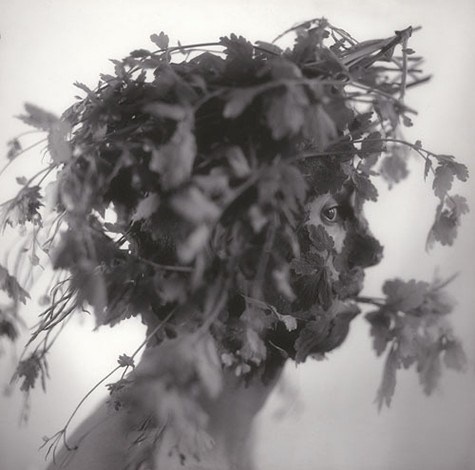

During its run at Yancey Richardson Gallery, Truppe Fledermaus was described by Vicki Goldberg, in her rave review in the New York Times, as “a lunatic, slyly humorous parable.” And indeed it is: The exhibition includes 100 photographs that chronicle the troupe’s exploits, as well as posters, sculptural vessels and elaborate set and costume sketches. The project was inspired by a subplot in the Strauss opera Die Fledermaus, in which a performer, inebriated and wearing a bat costume that is too tight to remove, is left alone in the woods, with tragicomic consequences. In their fantastical take on this, Kahn and Selesnick play two characters from the opera, Falke and Orlofsky, whom they refer to as their alter egos.

Over the years, the collaborators, despite sometimes living thousands of miles apart, have created more than half a dozen such fictional universes. “They’re two of the most wildly inventive artists of our time, which is why their fans are so devoted,” says Yancey Richardson, who describes the artists’ work as the intersection of “sustained collaboration” and “boyish improvisation.”

Their first large project, begun more than 20 years ago, followed the Royal Excavation Corps, a hardy band of archaeologists who, Selesnick says, fabricated “the very objects they were attempting to discover, causing a kind of feedback loop.” Kahn notes that they were also “investigating a method of engineless gliding that involved ingestion of hallucinogenic honey.” Then came an expedition to the moon, and another to Mars, documented as if they had really occurred, but with a lunacy that made it quite clear they could never have happened.

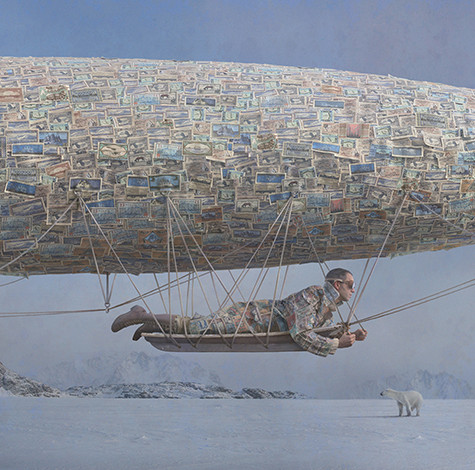

Along the way, the artists detoured to the City of Salt, a paean to sacred architecture (inspired in part by Buddhist stupas), and to Scotland, where the seemingly primitive inhabitants of their Scotlandfuturebog communicated telepathically. (The published version of Scotlandfuturebog was named both the best photography book of the year by the New York Book Show and the quirkiest photo book of the year by the Village Voice.) For a 2007 project, Eisbergfreistadt, they documented a masked ball held on a large iceberg off Lübeck, Germany, during the great hyperinflation of 1923.

Artists hoping to become overnight successes — and what artist isn’t? — should take a lesson from Kahn and Selesnick, who have enjoyed slow and steady growth both of their critical reputation and sale prices. Their work is owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and, fittingly, the Smithsonian Institution, as well as countless private collectors.

Kahn grew up in New Jersey; his father was a TV cameraman and his mother a narrator of Movietone newsreels (which explains plenty). Selesnick was born in England to an artist mother and mathematician father and was raised on both sides of the Atlantic. They met as high school seniors while competing for an art scholarship at Washington University, in St. Louis, and quickly discovered they liked the same British artists and writers. Starting freshman year, they worked together on a number of art projects. After graduation, Kahn moved to New York — specifically, a tugboat in the Hudson River — to work as a printmaker and photo assistant. Selesnick lived in London and St. Louis and pursued architectural photography. But after several years apart, they decided to renew the collaboration they had begun as undergraduates. Says Kahn, “We missed the joint energy and power that we found in college and decided to create a real collaboration.” In 1988, both men moved to Cape Cod to become “Kahn & Selesnick.”

In their early days, working in small spaces with limited budgets, they used ordinary printer paper, stitching together 8-by-11 sheets to create fake panoramic photos of the Royal Excavation Corps. The roughness of the images, sepia toned and deliberately creased, helped make them seem like vintage photos. (The first time I saw their work, in a gallery window on Cape Cod, I thought it was a flea-market find; that was before I knew about the artists’ flea-market imaginations.)

But, over the years, their photographs have become bigger, more colorful and more phantasmagorical, as they have had more money to spend on cameras, costumes, props — and travel. They have used as backdrops some of the most other-worldly locations on the planet (Iceland, Nepal and Death Valley, among them). Technology, meanwhile, has allowed them to manipulate images, combining elements from separate frames into dazzlingly complex compositions. “We tend to be somewhat hasty photographers,” says Selesnick, “so we rely on being able to do things on the computer. Sometimes, when we photograph, we have no idea what the final image will look like.”

Photoshop solves that problem, and then some: The images in “Truppe Fledermaus” represent a wide variety of styles. “We’re raiding the history-of-photography larder,” says Selesnick, who, like Kahn, has an encyclopedic knowledge of what came before. When Selesnick mentions that Die Fledermaus was often performed during the era of the Vienna Secession, Kahn reels off a list of Secessionist painters, including Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, who have influenced their work.

But Schiele and Kokoschka weren’t partners like Kahn and Selesnick, who have had an unusually long collaboration for a pair of artists who aren’t romantically involved. Intense periods of discussion and photos shoots at which both men compose — and pose — alternate with time apart when they produce images on easels and computer screens. “Being able to go back to our rooms gives us creative freedom after the time together,” says Kahn. “We both need both.” But authorship is always joint. After all, this is a partnership based on a shared sensibility, and, perhaps, a shared fate. Like the Truppe Fledermaus, Selesnick says, he and Kahn delight in “having an extra dimension to inhabit, a haven in which to process our existential anxieties.” Besides, says Kahn, “You can’t be a traveling circus by yourself.”