October 20, 2024For photographer Jonathan Becker, this fall is bringing some long-overdue closure. After a 15-year delay, his fifth and latest book is finally being published. Indeed, its Proustian title, Jonathan Becker: Lost Time, may well be a slightly winking reference to the lag between the volume’s conception and its release. A mock-up of it sat on Becker’s coffee table for 15 years.

Despite Becker’s illustrious career as a contributing photographer for the likes of Vanity Fair, W, Town & Country and Interview (back in Andy Warhol’s day) and his brilliant portraits of such boldface names as Gwyneth Paltrow, Diana Vreeland and Charles, Prince of Wales, the book had no takers when he and photography writer Mark Holborn first shopped it around, in 2009. That changed with publisher Phaidon, and Becker and Holborn have updated the mock-up with new material.

“The publishers we talked to initially wanted it portraits first and then landscapes, chapter by chapter, but that kills the story,” says the photographer, who envisioned a more idiosyncratic structure, organized around evocative juxtapositions rather than by subject, style and time period. “This is a visual narrative.”

Indeed it is, one that reveals how Becker took a flier on photography as a very young man and turned it into a storied career. The tale continues in a companion exhibition, curated by Holborn, on view at the Katonah Museum of Art until Jan. 26. (Becker splits his time between Bedford — the Westchester County town in which Katonah is a hamlet — and New York City.)

In the public imagination, a Vanity Fair photographer is likely associated with juicy color images of celebrities. Becker’s oeuvre, however, leans heavily into glorious black and white (a category to which more than half the book’s images belong). That format is Becker’s true romance, the mode with which he started his career and the one he still prefers.

Not coincidentally, it is also the format explored with an elegant touch by his mentor Brassaï, the Hungarian-French photographer best known for capturing the glory of Paris in the 1920s and ’30s in the silvery gray tones that once represented the entirety of photography’s range.

Like a lot of purists, Becker talks about black-and-white photography as the medium’s standard, a way to see the world reduced to its essence without distraction.

“Sometimes color is a confusion,” says Becker. “Black and white is simpler, it’s pure composition. It takes away, and less is more.”

In his magazine work, he got used to working in color and still uses it when making commissioned portraits. But it’s clear he finds it less satisfying. “Color pictures sometimes are just about the color,” he says.

Becker’s route to aesthetic awakening was untraditional. In 1973, the then-18-year-old New York City native, took a course at Harvard Summer School about Surrealism, since the history of the world between World War I and World War II had always fascinated him.

His professor, an acquaintance of Brassaï’s, encouraged Becker to send the legendary photographer a paper he’d written about photography and Surrealism. “Brassaï wrote back saying it gave him great satisfaction, and that I had understood and expressed the spirit in which he photographed,” says Becker, who first used a Brownie camera as a child and discovered the joys of shooting with a Rolleiflex as a teenager.

Brassaï’s letter, Becker says, was more than encouraging. “I thought I could take that to Saint Peter. I was ready to go. And that was the end of any formal academic training.”

Not too long after, Becker moved to Paris and began a year under Brassaï’s tutelage. The day they met for the first time, Becker captured a haunting shot of an empty baby carriage in a hallway of Brassaï’s apartment building, which features prominently in Lost Time.

“It’s a very meaningful image for me,” says Becker, who didn’t know at the time that Brassaï and his wife had never had children. “The magic of photography is that you recognize things visually without having to articulate them in some way.”

During the final 10 years of Brassaï’s life, Becker captured him in several black-and-white portraits, all made with a Rolleiflex, a brand of camera he still uses. Brassaï was an easy subject, as long as Becker didn’t snap too many times.

“He only ever took one, two or three frames of a subject, max. He was disciplined,” Becker recalls. “From him, I learned that you think before you take pictures, even if it’s a quick think.”

The very last of Becker’s portraits of Brassaï, also in the book, was taken the evening before he died (in 1984, a decade after Becker first arrived in Paris), showing the legendary lensman casting a large shadow on the wall, another example of a photograph that seems now to be full of prescient meaning.

Certainly, Becker took the lessons of his mentor and evolved his own style. The book’s black-and-white images show his ability to be in the right place at the right time, and then to snap the perfect moment with his handy Rolleiflex.

“For color you needed lights and a tripod, and I didn’t have either,” he says of starting out. “They’re aggressive, and you miss things.” Instead, he combined a stealthy patience and an easy sociability.

A 1988 party photograph of William F. and Pat Buckley shows the couple with faces so animated that it calls to mind the images of Weegee, the famed New York City chronicler of crime and nightlife, verging on grotesque. In silver and black, Buckley’s jowls look like they were carved in stone. “Color would have been extraneous,” Becker says.

A charming 1984 image of two French butchers, one of them holding a pig’s head, is so sensitively and empathically rendered that it could be by the great German photo portraitist August Sander, except for the fact that you can see the hands of Becker’s assistant peeking over the backdrop he was holding, adding the slightest postmodern touch.

La Chasse Au Cerf (Deer Hunt), a 1975 image taken in Normandy, depicts a shady scene deep in a forest in which the dark tree trunks form strong verticals, with the hunting dogs gathered at the bottom of the frame.

“That was pushing the limits of black-and-white,” says Becker. “I ‘pushed’ the film a few stops which means that the photograph is underexposed and then overdeveloped in compensation.”

Given Becker’s star-studded career, it’s no surprise that portraits of the well-known may beguile Lost Time readers the most. Consider his 1988 shot of Robert Mapplethorpe, taken toward the end of a life cut short by AIDS. In the photo, the sober-faced artist is seated at a Whitney Museum of American Art event, surrounded by eager attendants.

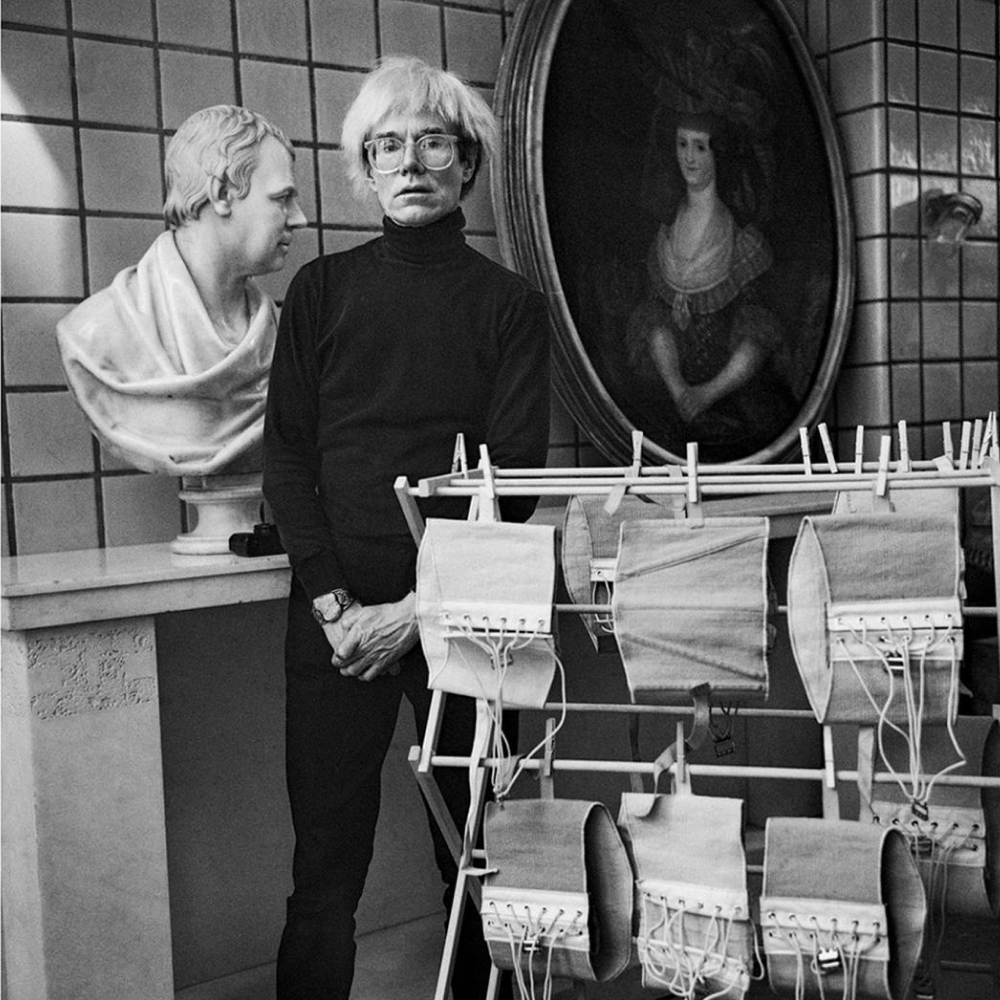

A 1986 image portrays Warhol next to a rack of corsets, which he needed to wear after being shot in the abdomen in a well-documented 1968 attack. Each was painted in a different day-glo hue, and Becker captured the scene in both color and black-and-white. For the book he chose the latter image, avoiding the distraction of the neon and instead letting the eye focus on the fact that Warhol is standing between a sculptural bust and an old-fashioned oil painting, a position that seems to insert him, somewhat awkwardly, into the sweep of art history.

Playwright Arthur Miller — seated by the edge of a pond in Roxbury, Connecticut, with his wife Inge Morath in the background — looks appropriately monumental in black-and-white, a format that Morath herself mastered as a well-known photographer for the Magnum agency. “Arthur Miller is walking history,” says Becker. “It would have been mundane in color.”

Miller, who would die just shy of 80, was then in his mid-70s. “There was something melancholy about the shot, which I have just begun to understand, as I just turned seventy,” says Becker, in what sounds like another nod to the title of his newly released volume. “This whole book punctuates time.”