October 25, 2020As a designer, James Huniford can do pretty much anything. He can make a room as glamorous as an Art Deco cocktail shaker or as utilitarian as a rusty metal tractor seat. He will take down walls for clients who want their apartments to be more like lofts, and he will put up walls for clients who prefer things cozy. He can do an apartment in all white or deploy chrome yellow and washed teal (a palette he adapted from a Morris Louis painting for a new house in Rhode Island).

“I look at my job as making people comfortable,” he says. In 2020, that has meant making people comfortable despite upheavals in their lives. Clients have been turning dining rooms into offices, making their kitchens multifunctional, replacing upholstered pieces in their children’s rooms with desk chairs. Huniford (whom everyone calls Ford) is happy to help out. “He has always cared about families, even before he had kids,” says Linda Wells, the legendary editor and entrepreneur, for whom Huniford designed a light-filled Upper East Side apartment. “It’s never about his ego — that’s unusual for someone who has reached the level of success that he has.”

But don’t think he has spent this year designing cabinets for computer printers. Huniford, who has two children and divides his time between Manhattan and Bridgehampton, has been working on several large projects, including a couple of new houses. For one of them, his firm is doing the architecture as well as the interior design. Huniford’s most recent presentation to the client — using 3-D modeling software and Zoom — was a big success, he says, except that the client wanted five windows in a room where he preferred just three. The client asked why, and Huniford explained that with five windows, the room would be hard to furnish; he needed solid walls as backdrops. The client assented. “People want a reason,” he says of his style of gentle persuasion. “It can’t be ‘Just because.’ ”

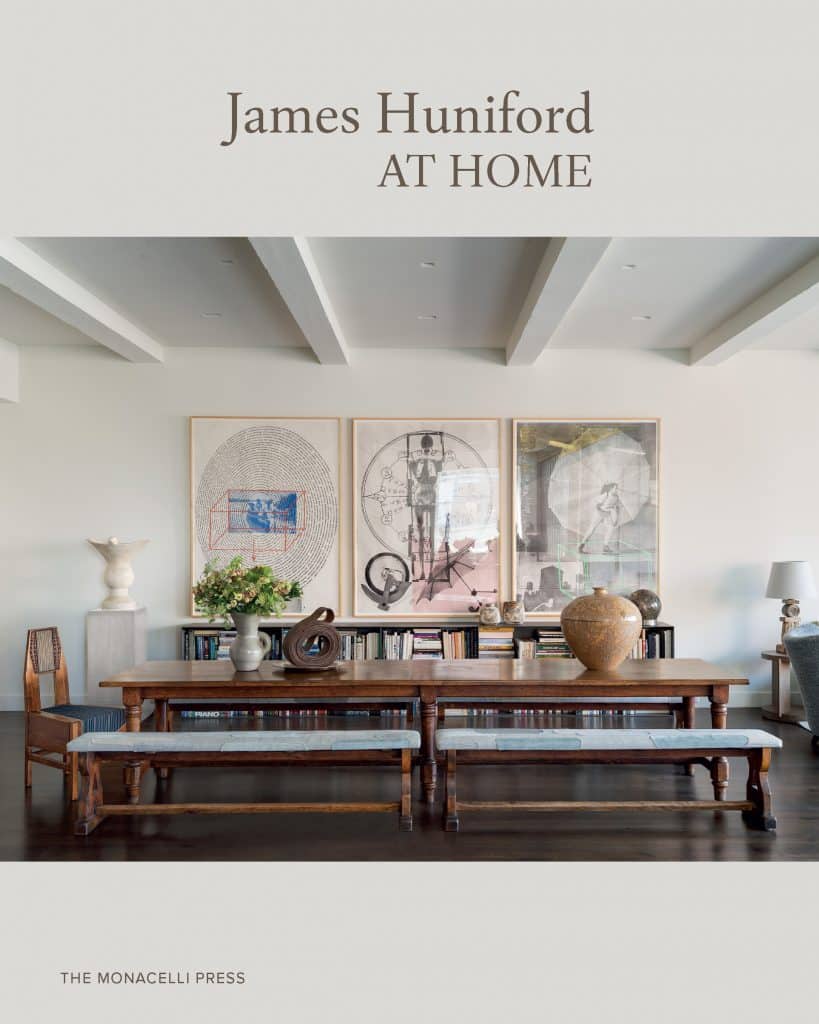

Cortland table and benches. Artwork by Maynard Monrow hangs over the vintage credenza, which is topped with a pair of Czech earthenware vases. Photo by Matthew Williams

Huniford can explain the reasons behind any of the hundred or so rooms in his new book, James Huniford at Home (Monacelli), which covers his 14 years of solo practice. It includes an apartment in the Gramercy Park area he created for fashion editor Ariel Foxman and his husband, Brandon Cardet-Hernandez. Huniford wanted to make sure the couple’s art collection, which includes a number of small works on paper, wasn’t overwhelmed by the decor. That meant keeping the background neutral. In the dining area, the designer took this idea to its logical conclusion, choosing the same sandy color for the floor and the table and the benches and the highly topographic vintage sideboard.

There are more small works on paper — in this case, a suite of 20 Henri Matisse prints — in the Westchester County farmhouse Huniford renovated for Jeffrey Seller, the producer of Hamilton, and the photographer Josh Lehrer and their children. Even with the Matissses on the walls, nothing about the house is pretentious. In the living room, Huniford responded to the art with the burnt-rust leather of vintage French armchairs and the colors of custom rugs from Stark. (The floor, he says, can be as important a surface as the walls, design-wise.)

The renovation of the couple’s house started out modestly — “We weren’t going to move any walls,” says Seller. But one thing led to another. “It was the classic situation where you have a loose thread and you start pulling it and you can’t stop,” says Seller, noting that Ford never pushed him to do anything he didn’t want to do. “He occasionally would bring in objects that Josh and I would never have chosen, like the stump table in the foyer. Seeing it made me wonder, ‘Is that my style? Is that who I am?’ But Ford said, ‘It’s a big gesture, but I think you need a big gesture there,’ and we realized he was right. That’s an example of his artistry.”

When it came to the breakfast area, Huniford went with humble elements like blue and gray linoleum (“I like the way it feels under your feet”) and a wooden chest that suggests, but doesn’t scream, Americana. Even the Ellsworth Kellys above the chest are — atypically for Kelly — monochromatic

A house in Nashville couldn’t be more different. The client wanted glamour, so Huniford made the interiors as silvery as a cloud (if clouds had walls of faux eel skin and carpets patterned on ancient Roman tiles). In a Manhattan pied-à-terre that’s white on white on white, Huniford added texture by covering the fireplace in pigmented plaster and the floors in doubleweave cotton rugs. For a new house on Long Island that is surrounded on three sides by water, Huniford is planning a palette based entirely on the lustrous insides of seashells.

He loves to mix thick and thin, old and new, shiny and rough. In the Seller/Lehrer foyer, a pair of delicate Majolica vases stand on the stump table. In a Marin County house, he hung a massive gridded 19th-century hardware-store cabinet on a wall between wire-thin Italian sconces.

Sometimes, Huniford looks for commonalities, not contrasts. He designed the dining room of a house in Water Mill as a symphony of circles: The Josef Hoffmann chairs have arc-shaped backs; the mirror is framed by the housing of an aircraft engine. The pleated-fabric shade of the custom fixture resembles a miniature hoop skirt. In the same house, he festooned a guest room wall with antique grain sifters. Their circular forms suggest movement, almost like bubbles rising in a champagne glass.

The sifters are typical of Huniford, who finds beauty in utilitarian objects. His discoveries (some offered on his 1stDibs storefront) include a late-19th-century electrical panel from a house in New York City. “It’s sculptural. It reminds me of the work of Donald Judd,” he says. He has turned old car jacks into lamps and hung an obsolete cranberry rake on a wall in East Hampton. There are balloon molds in his Manhattan apartment and snowshoe molds in his house on Long Island. (Huniford’s own residences are two of the most appealing projects in the book.)

Huniford often designs stairways that are themselves compelling utilitarian objects. Gut-renovating a duplex loft on Bond Street, he tore out a straight flight and inserted a graceful spiral. “It was a total transformation,” he says. For a house in Amagansett, he installed stairs whose means of support are practically invisible.

When he can’t find the furniture he wants, he designs it. (Many of the resulting pieces are available as part of the his collection on 1stDibs.) But he doesn’t do overstuffed sofas; he likes his upholstered pieces, no matter how big, to be tailored. And he doesn’t like exposed-brick walls, which he finds cold and which remind him of his (dreary) first apartment in Manhattan. The landlord wouldn’t let him paint the brick, so he found a way to cover it in muslin.

Don’t be surprised, though, if someday he decides to place an overstuffed sofa against a bare brick wall. Of the Rhode Island house’s teal and yellow palette, he says, “I wanted to do something new, something outside my comfort zone.” Luckily for us, his comfort zone keeps getting bigger.

James Huniford’s Quick Picks