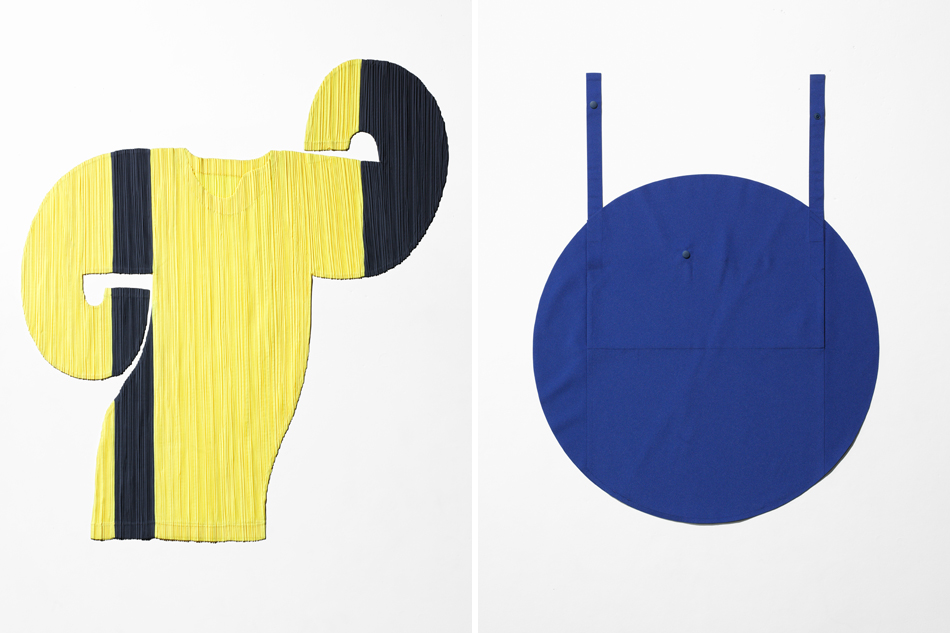

July 25, 2016The innovative, artistic and often architectural creations of Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake have won him a loyal following of sophisticated tastemakers (portrait by Brigitte Lacombe). Soon to be featured in the show “Shock Wave” — opening at the Denver Art Museum September 11 — Miyake was the subject of a just-closed exhibition at Tokyo’s National Art Center that featured the three outfits seen at top. All photos by Hiroshi Iwasaki unless otherwise noted

Grace Jones, Joni Mitchell, Zaha Hadid and Steve Jobs — they have all been Issey Miyake aficionados, each with a powerful yet radically different image.

When the founder of Apple asked the Japanese designer to make him a black turtleneck, Miyake delivered 100. Jobs, with his gift for establishing brand identity for his products, now had a signature look for himself.

There may be no label other than Issey Miyake with such a diverse band of fans, both celebrated and — like myself — otherwise. Some of us are conservative dressers, others look-at-me extroverts. We vary in shape, size, height, weight, age, race and gender: Mark Hodson, the owner of andARCHIVE, a vintage shop in New York that carries hundreds of Miyake pieces, reports that a petite French woman recently tried on a garment that looked as terrific on her as it had on the 300-pound man who’d stopped in the shop earlier that day.

Gender fluidity was built into the brand long before the phrase was coined. It was part of Miyake’s cultural legacy: Japanese women and men have been wearing the kimono for centuries. The designer has always valued tradition, even as he looks to the future. He has said that for him, “designing is an act of discovery,” and it would appear that many of these discoveries were born of thoughtful negotiations between the past and where he wanted to go next.

Miyake debuted this dress — made of recycled plastic bottles and featured in the recently closed Tokyo show devoted to the designer — in Paris in September 2010. It was born out of the work of his studio’s Reality Lab, whose small team of collaborative designers devote themselves to research into the future of making things.

In more than 40 years of exploration, the designer, now 78, along with his team, has boiled, shrunk, recycled, crunched and — most famously — pleated textiles. To create the last effect, Miyake transformed an ancient technique, devising a unique process of heat-pleating a garment after it is stitched. The result: permanent pleats and pleats that can hold unexpected, shifting forms as the wearer moves.

For too long, Miyake has been pigeonholed as an avant-gardist. But we who wear his clothes know that he’s a pragmatist, too, creating garments that are well suited to everyday needs. Most of his pieces are indestructible and still look “cool” years after they were bought. They are often lightweight, take up minuscule suitcase space and on arrival are ready to go, wrinkle-free. What’s not to like?

Here, especially, is what to love: On a hanger or laid out on a shop’s display table, his designs appear only as swirls of pleats or folded squares of cloth — interesting but mysterious. Slip an item on, however, and a kind of magic occurs. Garment and body bond in unexpectedly delightful ways, clinging perfectly here, creating intriguing volume there.

Such ideal symbiosis between garment and wearer doesn’t always happen, of course. But collecting pieces from his design studio’s different lines — Issey Miyake, HaaT, Cauliflower (known as “me ISSEY MIYAKE” in Asia), Homme Plissé, 132 5., Pleats Please and the handbag series Bao Bao — has educated me. I am more confident; I no longer think of clothes as something to hide inside. For me, as well as for their creator, Issey Miyake clothes are acts of discovery.

Through September 5, Mikaye fans can see key examples of his transformative clothes in “Manus x Machina,” this summer’s blockbuster at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, which highlights the work of a select group of designers focused on handwork and/or technology.

Coming up: “Shock Wave: Japanese Fashion Design, 1980s-90s” opens at the Denver Art Museum on September 11. Here, too, Miyake pieces are in the spotlight. Designs from two decades will be displayed along with fashions by Paris designers he inspired — among them Jean-Paul Gaultier and Azzedine Alaïa — depicting a chain of influence that continues to this day.

One gallery in the Tokyo show examined Miyake’s pioneering work from the 1970s, including the Hendrix/Joplin tattoo body suit (foreground), as well as a baseball-uniform-inspired outfit from Autumn/Winter 1972 (second piece from front). Photo by Masaya Yoshimura

Across the globe, “Miyake Issey Exhibition: The Work of Miyake Issey,” which recently closed at the National Art Center in Tokyo, was a major show conceived and curated by the designer himself. (The richly illustrated catalogues for all three are well worth having; the bilingual Japanese book includes often touching and illuminating essays by photographers, critics, museum directors and artists.)

The Tokyo show was divided into three parts. The first focused on the 1970s, the decade of feminism and with it the desire to move fast and freely. It featured arresting tattooed-looking body suits — decades before actual all-over tattooing became the rage.

The second section showed how, in the 1980s, Miyake engaged in creating sculpture for the body, using materials beyond fabric (metal, silicon, rattan and bamboo) to construct fashion-art for powerful women. The last and largest part of the show returned to the land of clothes, displaying Miyake’s most fabulous, imaginative, inventive and, above all, wearable pieces.

The ’90s gave birth to Pleats Please and A-POC (short for “a piece of cloth”), a line of garments made from single swathes of cloth. During this time, Miyake experimented with rayon, horsehair, raffia, silk bonded with foil, recycled polyester and paper. Alpaca and cotton also yielded fabulous frocks.

The Met offers a star piece from this last period: Colombe, a white dress named for the dove of peace, is made of monofilament fiber that is cut using heat, not scissors. Shown flat against a wall, it looks like an irregular rectangle with two leather straps attached and a few snaps that articulate some folds. But on the adjacent mannequin, it comes to life as a sharp and sassy one-shoulder dress. Made in 1991, it looks as fresh as a dress on the summer 2016 catwalk.

andArchive’s Mark Hodson, a longtime collector of Miyake, observes, “Fashion is so individualist now that as long as you are ‘owning’ it, you can wear anything you want.” The exposure given Miyake by these museum shows and their accompanying catalogues should encourage many more women and men to own his clothes, in both senses of the word.