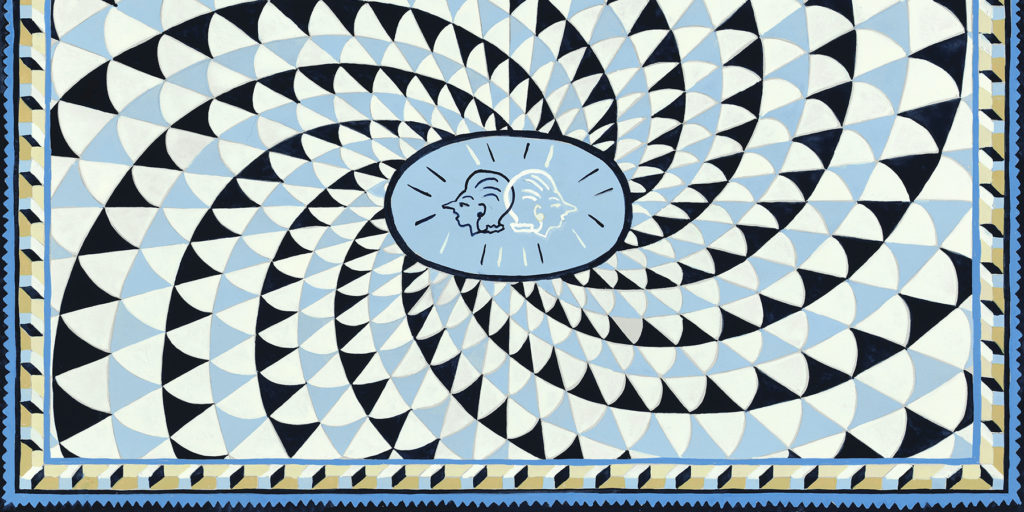

October 17, 2016Eerdmans Fine Art and Jane Stubbs Books & Prints have mounted a Manhattan exhibition celebrating the work of enigmatic mid-20th-century French designer Emilio Terry, one whose drawings, from 1913, is shown above. It’s on the letterhead of the Hotel Inglaterra, in Havana, which was owned by his family. Top: For the exhibition, illustrator Konstantin Kakanias created works in which his character Mrs. Tependris is inserted into Terry designs, as in this reimagining of one of his carpets.

Emilio Terry, an architect and designer who frolicked in the top echelon of French society in the middle of the 20th century, now seems like a man of mystery. Despite having applied his artistic vision to numerous historic residences and collaborated with such artists as Salvador Dalí and Alberto Giacometti, as well as with designers like Jean-Michel Frank and Serge Roche, his oeuvre today is relatively unknown outside a small circle of taste-making admirers, Robert Couturier and Alexa Hampton among them.

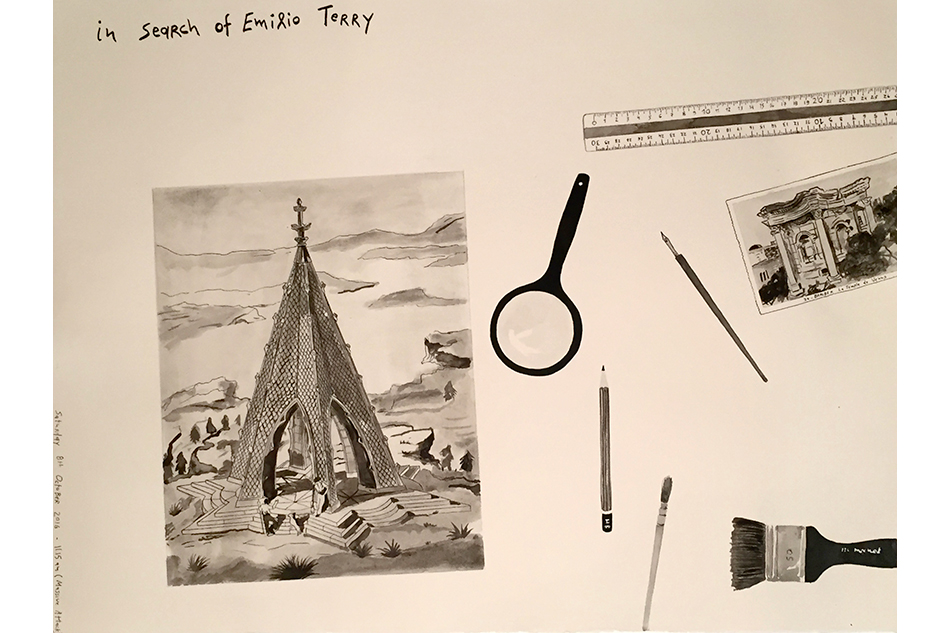

The exhibition “In Search of Emilio Terry” — organized by Eerdmans Fine Art and Jane Stubbs Books & Prints and on view October 20 through November 12 at Eerdmans’s New York gallery on East 10th Street — aims to shed a little more light on the Frenchman, whose family made a fortune in Cuba’s sugar cane trade and whose father owned the Loire Valley’s famous Château de Chenonceau, built in the early 1500s.

“He came from a very wealthy family and could afford to simply follow his passions,” says design historian and gallerist Emily Evans Eerdmans, referring to Terry’s unique style and way of working. Jane Stubbs concurs. “He was able to be very selective about the jobs he took on,” she says. “He was never under financial pressure, and he also had a life as a society figure.”

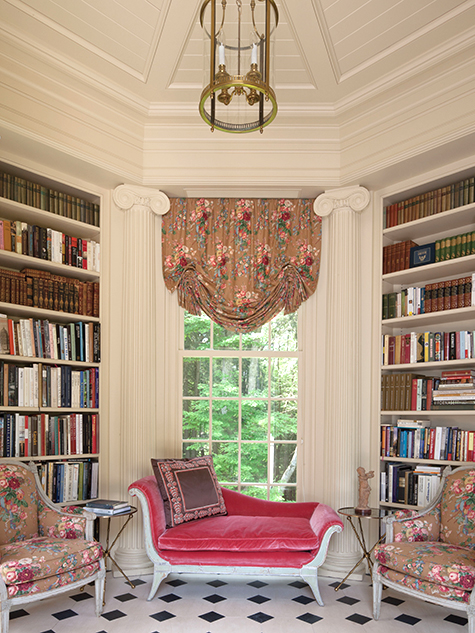

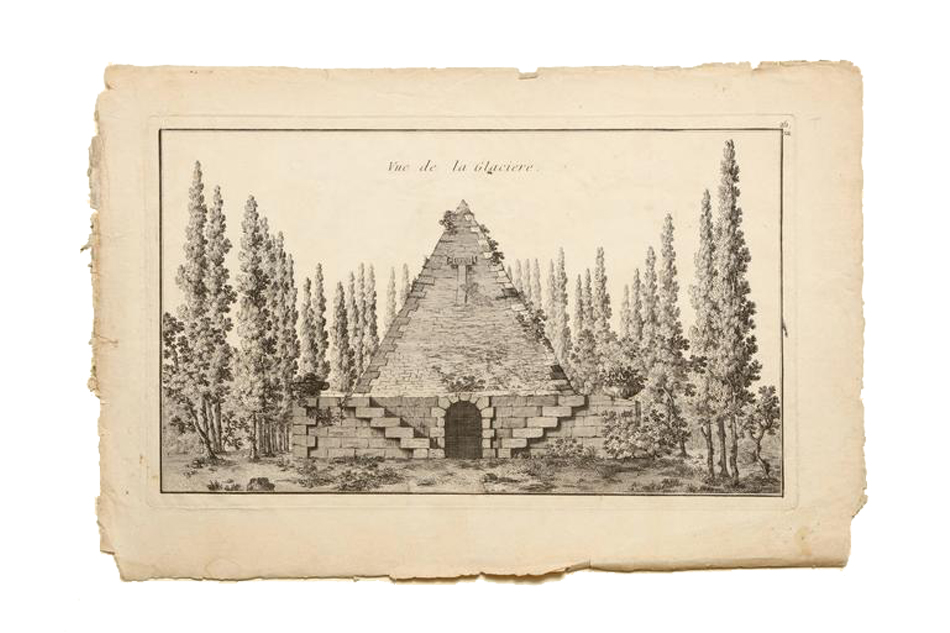

Terry’s clientele included the cosmetics czarina Helena Rubinstein and shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos. And his most acclaimed project was the redesign and expansion of the early 19th-century Château de Groussay, just west of Paris. The client was the eccentric art collector and lavish party organizer Charles de Beistegui, for whom Terry added an elaborate theater and numerous large-scale garden follies, including a Chinese pagoda and a structure resembling a tent.

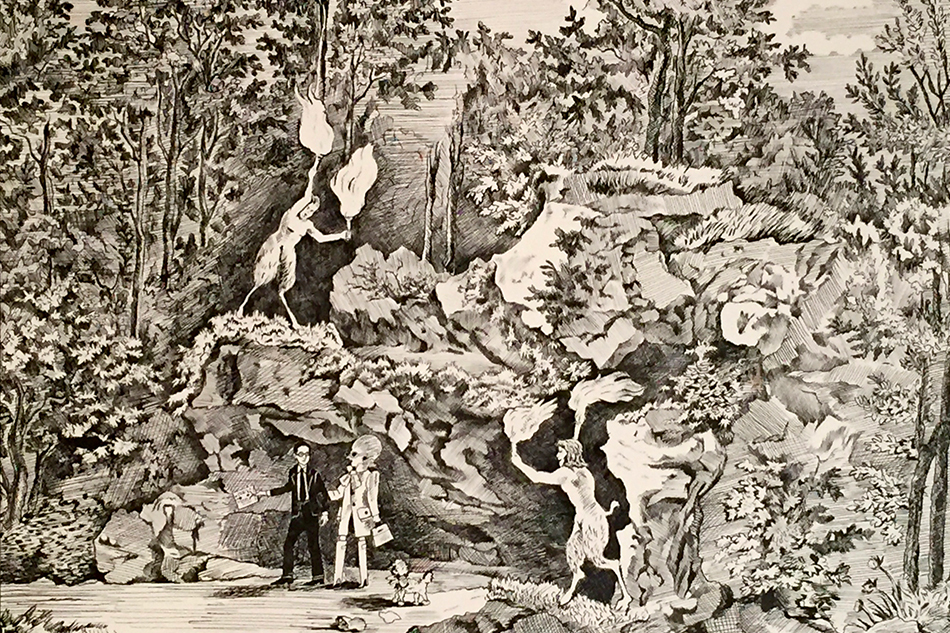

Intertwining threads of neoclassicism and fantasy gave many of Terry’s creations a remarkable originality. In the 1930s, he explored Surrealism. During this phase, he produced works like a model of a spiral-shaped building (which appears in a portrait Dalí painted of Terry) and a drawing of a waterfall cascading down upon a fireplace, both of which appeared in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1936 survey of the Surrealist movement.

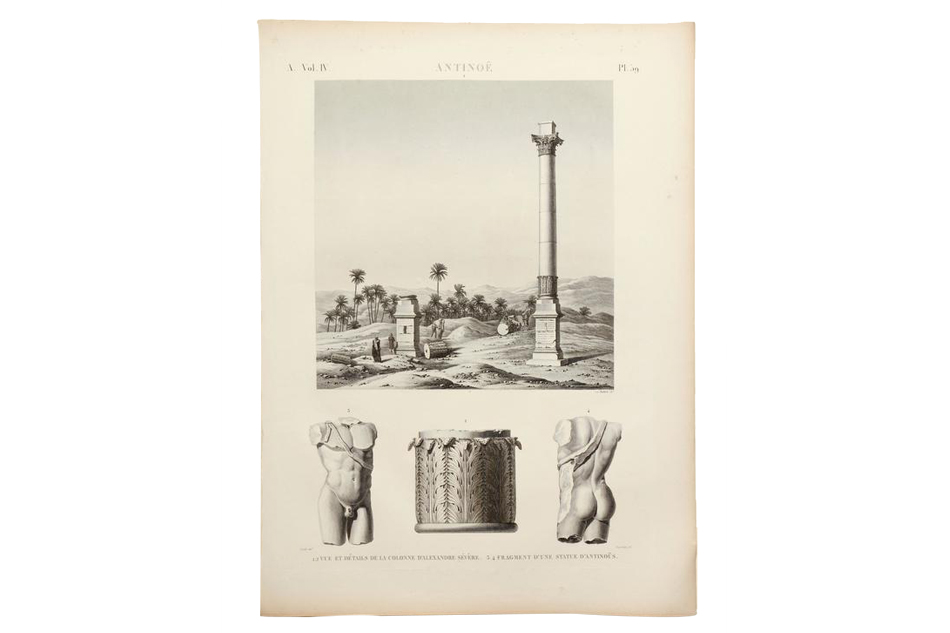

The MoMA exhibition catalog contrasted his approach to that of Le Corbusier. While the latter insisted that a home be a functional machine for living, it noted, “Terry feels that a building should be ‘a dream come true.’ ” Even as he worked in the realm of fantasy, however, Terry searched for inspiration in real life, traveling extensively in order to mine the past for examples of both earlier French design and classical architecture. The result was a style he dubbed “Louis XVII.”

Reflecting Terry’s often playful approach to design, Eerdmans and Stubbs created an exhibition that, rather than chronological and comprehensive, is free-spirited and full of both history and humor. “We wanted to make it about his world — what Terry was getting influenced by and whom he was influencing,” says Eerdmans.

The pieces on view include 17th-century architectural engravings and 18th-century etchings by Piranesi — Terry had editions of both in his personal library — as well as drawings by such Terry contemporaries as Christian Bérard and Jean Cocteau. “We’re trying to draw connections and show how these things inspired what Terry did for himself and his clients,” says Eerdmans. There are also furniture pieces that Terry designed for the Château de Groussay, on loan for the show, along with work influenced by his designs.

In another Kakanias work, It was just too much. Her life. / This sick obsession with J.L. . . . / (xanax overdose), Mrs. Tependris is shown collapsed on the floor of the theater at the Château de Groussay, which Terry designed for playboy collector de Beistegui. (J.L. are the initials of socialite Prince Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucinge, a member of Terry’s coterie.)

But the centerpiece of the exhibition is a new series of paintings by Konstantin Kakanias, an illustrator best known for his witty take on the fashion world, seen through the eyes of his fictional high-society character Mrs. Tependris.

“It’s through her that I’m revisiting his work,” says Kakanias, who invented a story about Mrs. Tependris’s relationship with Terry. “She was a client, and they were trying to finish a project, but I think it was over,” he says. “There was also a sentimental affair with a friend of his — it’s complicated.”

Among the pictures is an image of Mrs. Tependris lying on the floor of the Château de Groussay’s theater after a Xanax overdose. “It was just too much. Her life. This sick obsession with J.L. . . .,” reads the accompanying text.

Another image presents a pattern taken from a custom carpet Terry designed for the Paris apartment of Raymond Guest and Princess Caroline Murat, which was based on a Greek mosaic floor. Mrs. Tependris has redesigned it as a beach towel, with her own long-nosed visage at the center.

“They’re glimpses of the story,” says Kakanias. “I wish I had had a year to compose the whole relationship. But it takes so long, using ink and gouache and time, to explain everything they went through.”