Growing up on a dairy farm in small town in New Zealand, Hugh Leslie says he didn’t even know what interior design was when his sister suggested he study it. Today, the London-based designer is among the U.K.’s most highly regarded (portrait by Mark Weeks). Top: A townhouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side features custom sofas, side tables, etageres and a walnut and pigskin hide stool. The fireplace is from Jamb and the artwork above it by David Hockney. The pieces flanking it are by Alexander Calder (photo by Lucas Allen)

I came for what we call O.E.,” says interior designer Hugh Leslie. “Overseas Experience. Thirty-two years later, I’m still having it.”

The New Zealand-born Leslie is sitting in his neatly organized London studio — fabric swatches pinned to the walls, architectural plans on a drawing board, wood samples in stacks — on a charming pedestrian street just opposite the South Kensington tube station. Outside, there are throngs of tourists heading to the Natural History and Victoria and Albert museums, and spilling out onto the patios of restaurants and cafés. But on the light-filled second floor of this terraced Georgian house, it’s all calm and quiet.

Raised on a dairy farm in the tiny rural town of Te Aroha on New Zealand’s North Island, Leslie wasn’t exactly destined to become an interior designer. Although he loved art classes at school, he says he didn’t even really know what interior design was when his sister suggested it as a potential career. He liked the sound of it, however.

“There was basically one course on offer, in Auckland,” he recalls, “but it was good and well-rounded. We did color theory, technical and life drawing and building construction, so a nice combination of the practical and the creative.”

Practical and creative might well be Leslie’s motto. Low-key and unassuming in person, he is the opposite of many stereotypes about brash, dictatorial designers. It’s easy to see how his calm presence and reassuring down-to-earth personality would endear him to his clients, who range from young entrepreneurs to established families.

In the dining room of the Manhattan residence, a 19th-century chandelier hangs above an ebonized table surrounded by colonial caned-back ebonized chairs. The 19th-century gilt candlesticks are from Guinevere London. Leslie commissioned the panel depicting an Henri Rousseau–inspired jungle scene for the room. Photo by Lucas Allen

Many of them have commissioned multiple projects from Leslie since he established his practice in London, 18 years ago. During that time, he has designed and renovated grand historic country estates throughout England (most recently one of Edwin Lutyens’s early houses in Surrey), a Regency villa in Oxfordshire, townhouses in London and New York and holiday homes in Switzerland and Ireland.

“I didn’t ever think I would run my own business,” he says. “But once I made the decision, opportunities arose and revealed themselves.” Leslie, who is regularly included in British House & Garden’s Top 100 and Country Life’s notable designer lists, says clients appreciate his ability, gained through years of experience, to “unleash a home’s potential for contemporary living. Allowing clients to see beyond the confines of the architecture opens the possibility of creating whatever you want.” He credits the time he spent early in his career working for some of the greats of English design — both traditional and modern — with giving him the foundation he needed for success.

During a recent hour-long conversation with Introspective, Leslie spoke about his early years in design, the difference between interior architecture and decoration and some of his favorite projects.

What made you move to London?

That’s where you headed if you were from the colonies! After working for a few years in New Zealand, mostly doing commercial design, I put a pack on my back and landed in London. There was a huge boom in retail, and I had no trouble finding a job. I was doing design for commercial properties when a friend suggested I try residential design. I found a job at Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler, working for a man named Chester Jones, who was a great designer and did quite a lot of modern work, although it was a fairly traditional firm. That really trained me to work on interior architecture — drawing up rooms and paneling and cornices.

In a sitting area of the townhouse, a Flexform Boss armchair faces a Vladimir Kagan–inspired sofa. Photo by Lucas Allen

Are those interior architecture skills important to your work?

Extremely. If you are just decorating a home and don’t understand the interior architecture side, you are missing a trick. Being able to draw well is a basic skill for a designer. It is really important to be able to communicate with a pencil and a bit of paper in front of a client. I think most design schools now teach drawing on the computer, and that’s a useful skill. But it’s not the same as showing you something quickly and easily in the moment, or giving ideas tangible shape.

Bleached, stained and polished Douglas fir clads the walls of a 1970s Swiss chalet Leslie decorated for repeat clients. The chairs are by Chester Jones, Leslie’s mentor at the London firm Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler. (Leslie continued to design with Jones after the latter started his own practice.) The textile on the back wall is from Cameroon. Photo by Joseph Condron

How did you come to start your studio?

Three years after I joined the firm, Chester Jones left. I worked for two other great firms, but in 1994, Chester asked me to join him in his own practice as a director. Chester was an architect, so we often did projects from the ground up, as well as the interior design and even the furniture. After a decade there, I set off on my own. Today, there are five of us, which is small, but I am a bit of a control freak and like to know exactly what’s going on. And I like to be involved with clients as well, which doesn’t happen as much when you get bigger as an organization. I am at ninety percent of our client meetings.

How do you approach new commissions?

Every project presents challenges, and a lot depends on the client. Some are very clear about what they want. Others have a less fixed idea, and there is the possibility of pushing boundaries and doing something they hadn’t thought about. We all have preconceived ideas, but it’s important to look at them and ask: Is that the right way? Sometimes you get a brief, but then you realize the project can be approached differently.

The first thing I talk to clients about is the purpose of their property. Is it the main residence, a holiday home, a downsizing apartment? Must it be child friendly, good for entertaining? Then, I start with the interior architecture, which gives you a chance to get to know the client, because it involves thinking about the way they live. I ask more questions: Where do you come in? Do you do the shopping, or does someone else do it for you? Do you watch a lot of television? Where do you pay bills or use your computer?

I also always think about making homes flexible, because life changes. Kids come and go, and a family’s needs change. But I don’t give a dozen choices. I need to lead, and I say, I think this is what you will be comfortable or happy with.

The dining room of a residence in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood centers on an antique chandelier and table, both from the homeowners’ collection. The Regency-inspired mantel, from Chesneys, is based on one designed by Sir John Soane for Norfolk’s Shotesham Park in 1790.

Can you talk us through a few key projects?

Clients we had done a few houses for bought a chalet in Switzerland, which they presumed would be done in a traditional manner. But after a lot of discussion and thought, we ended up doing something quite contemporary. It was a nineteen seventies building, not graced with high ceilings or great proportions. We reclad it in a lighter wood, redid the windows and balustrades using local materials, painted everything in a cool palette and just made it look more modern. I designed most of the furniture, using solid oak, and put a new staircase in. Comfort and maximizing the impact of the beautiful views were paramount, so there is nothing showy about the interior.

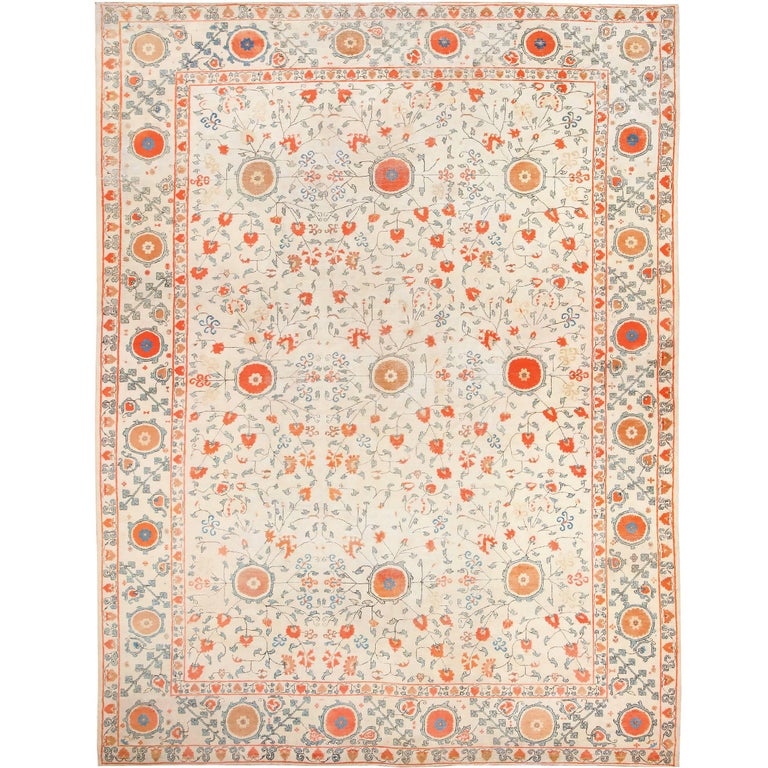

A star-like pendant from Vaughan Lighting hangs in the hallway outside the dining room of an Oxfordshire home. On the wall above the dining room’s console table is a 19th-century suzani. Photo by Andreas Von Einsiedel

We also did a mansion on the Upper East Side of Manhattan for great clients who were very adventurous and really loved pattern and color. We commissioned a lot of furniture and carpets from craftspeople and had artists do a set of carved panels to line the dining room’s curved walls. We did limewood panels with a Henri Rousseau–inspired design of climbing monkeys. We also bought some lovely antique furniture, including a set of colonial ebony and cane chairs for the dining room and a set of Frank Lloyd Wright tables for the living room. I love pieces that have a handmade quality.

Another great project was a townhouse in Kensington. It was a beautiful period home, and we retained some of the existing interior architecture and joinery. But we found lovely, more-contemporary fireplaces at Jamb, a specialist English company, and put in modern carpets that have a nice handmade quality and patina. We frequently start with carpets to ground a room, and I like stripes because you can create a contemporary or traditional scheme around them. We designed all the cabinetry in the kitchen, and it’s fairly traditional. I like the contrast of the LOVE tapestry by Paul Smith for The Rug Company and the Tom Dixon light over the table. In the bedrooms, we put fabric on the walls, which creates a lovely soft, luxurious feel. The master bedroom has wall and curtain fabric by Kerry Joyce, and the cushion on the bed is by Fortuny.

Do you feel you have a distinctive style and aesthetic?

In the end, those come down to the property and the client. I don’t usually have any issues with aesthetic tastes because the people hiring you have looked at your portfolio and seen something that they feel attracted to. Ultimately, I’m guided by the needs of the clients. If they want something and I disagree, well they are the clients. And, you know, they just might be right.