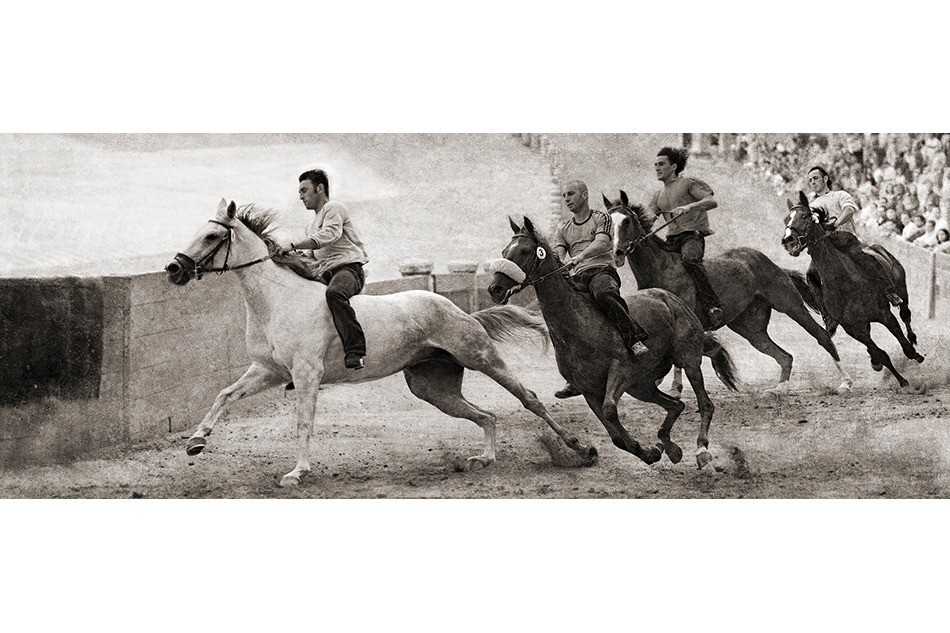

For millennia, the majesty and musculature of the equine form have spurred the creativity of artists around the world, inspiring images ranging from the 17,000-plus-year-old cave paintings at Lascaux, France; to a Han Dynasty terra-cotta equestrian soldier made in China between 206 BC and 9 AD and offered by Pagoda Red (above, photo courtesy Pagoda Red); to contemporary works like Pete Kelly’s 2010 photograph Blur Stampede, Marple Cheshire UK, offered by Robin Rice Gallery (top, image courtesy Robin Rice Gallery NYC).

October 31, 2016Sorry, dog lovers — as many of the equestrians attending Lexington, Kentucky’s National Horse Show this week know, although the tradition of painting canines is a long and charming one, nothing comes close to the legacy of the horse in art.

The most important domesticated animal in the history of man, the horse has been the keystone, at various points, of agriculture, military might and sport. Dogs have kept us company, but they haven’t put food on the table or helped us win a war the way that horses have.

The horse’s size and form — and its unparalleled speed and grace — first captured man’s imagination thousands of years ago, and they continue to do so today. The 17,000-plus-year-old cave paintings at Lascaux, France, demonstrate this dramatically: The horse was sketched as soon as there was sketching.

This long relationship between artist and horse is also on display at Chicago’s Pagoda Red, which specializes in 18th- and 19th-century Chinese furniture and decorative arts, including a pair of circa-1900 lacquer horses currently on offer.

“The Chinese have revered horses in art for thousands of years,” says Pagoda Red owner Betsy Nathan. Case in point: the gallery’s charming terra-cotta soldier mounted on a trusted steed, which dates back to the Han Dynasty. It isn’t nearly as old as those French cave paintings, of course, but it does provide evidence for humans’ love of the horse as far back as the 3rd century B.C.

Since those long-ago days, a bit of a hierarchy has evolved. “In terms of animals in art, for value it’s horses first, then dogs and then pigs,” says William Secord, a Manhattan dealer who’s made a specialty of fauna. (As for the lower end of that hierarchy, one well-known art critic has been known to remark that cows in a landscape are “a definite downer.”)

The dining room of a South Carolina home by New York– and New Orleans–based society decorator Thomas Jayne embodies his advice to use equestrian artworks sparingly. “If you put them everywhere to imply you have ancestors, they cease to be fine art,” he cautions. Photo by Pieter Estersohn

Although there have been plenty of memorable sculptures of horses — just think of every public plaza with a horse-mounted military officer (the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Michelangelo’s Piazza del Campidoglio, in Rome, is an exemplar), or the rearing energy of a Frederic Remington bronze — “they’re nothing compared with the pictures,” says Secord, who sells everything from charming anonymous prints worth a few hundred dollars to a study by the great Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959) priced at $150,000.

Experts agree that the apogee of equine art is represented by the British hunting and racing pictures of the 18th and 19th centuries, first and foremost those by George Stubbs (1724–1806) but also examples by Edwin Landseer (1802–73) and Munnings. France was a close second in the same period, with Alfred de Dreux (1810–60) and Rosa Bonheur (1822–99), whose landmark painting The Horse Fair (1852–55) is a favorite of visitors to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and helped make her perhaps the best-known female painter of the 19th century.

As for collectors of horse pictures, the greatest was arguably the Anglophile American financier Paul Mellon — he’s the man you went to see about seeing a horse. Many works from his holdings are on view in the museum he founded, the Yale Center for British Art, in New Haven, Connecticut, which recently renovated its beautiful Louis Kahn building. The Long Gallery there has a sporting theme that displays “Mellon’s great love for horses and for the artists who specialized in depicting them,” says Scott Wilcox, the center’s deputy director for collections. Wilcox’s personal favorite among the works on view is James Ward’s 1809 Eagle, a Celebrated Stallion, which he characterizes as “the epitome of the horse as Romantic rock star, an uncanny combination of power and sensitivity.”

Also represented by Sears-Peyton, Jane Rosen uses media that range from charcoal to Provençal limestone to create her figurative two- and three-dimensional artworks. For 2015’s Cash Akhal Tekke, a detail of which is shown here, she worked with beeswax, charcoal, ink and coffee. Image courtesy Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, Los Angeles

Manhattan’s Sears-Peyton Gallery exhibits several artists who could be said to focus on the mane event, including Jane Rosen and Thomas Hager. The California-based Rosen paints and sculpts horses and other wildlife on her ranch, working with equal virtuosity across a variety of media, from hard Provençal limestone to soft charcoal on paper. Hager, for his part, does cyanotypes and pigment prints of horses, giving an elegiac and timeless quality to his subjects.

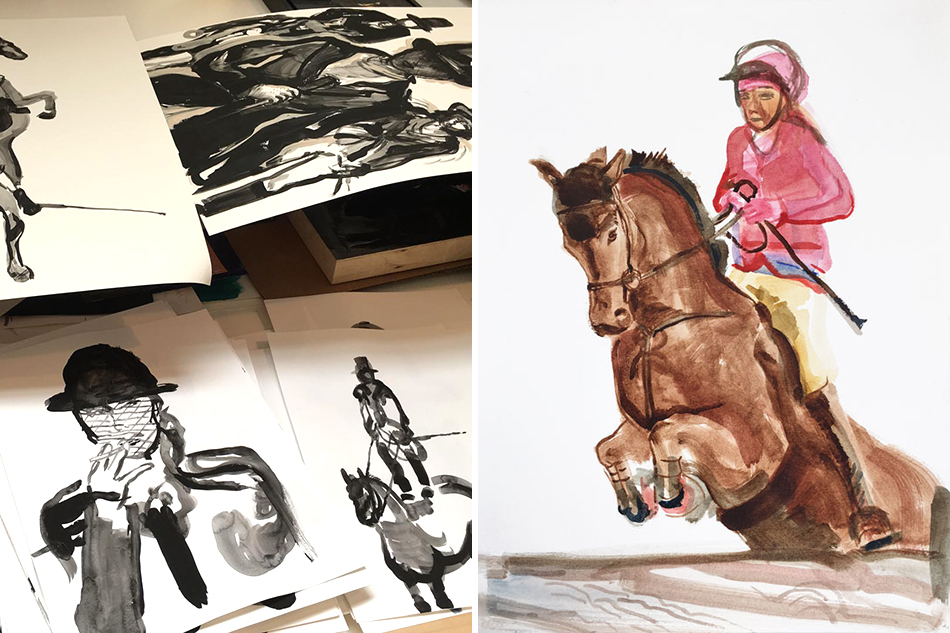

Another Sears Peyton artist, Brooklyn- and Vermont-based Suzy Spence puts her own modern-day spin on English sporting art. “I love these paintings, with all their tension and complexity, and I return to them again and again,” says Spence, who makes loosely painted, charmingly gestural scenes. “They’ve come to represent refinement, but what many people don’t know is that this manly sporting life was actually quite debauched.” Spence cites both the Lascaux cave paintings and painter Susan Rothenberg’s well-known contemporary series of abstracted horses as secondary inspirations.

After you purchase a fine picture of a horse, placing it carefully in the home is the next hurdle. “They’re immediately evocative,” says society decorator Thomas Jayne, who is based in New York and New Orleans. “They can be of modest quality and still be interesting.”

Jayne offers one caveat: “If you put them everywhere to imply you have ancestors, they cease to be fine art. Beware the false note. And those prints of red-coated riders jumping over fences are too ubiquitous to be a good idea,” says Jayne, who can’t resist adding, “Don’t horse around with it.”

Markham Roberts, the Manhattan-based decorator who works often on the Upper East Side and in the Hamptons, has had his fair share of projects that entail artfully arranging depictions of saddles and crops. For a 1920s home in Nashville that was featured in his 2014 book Markham Roberts: Decorating The Way I See It (Vendome Press), his clients were a family of racers and breeders.

Of former sidesaddle champion Jane Williams, Moore writes that horse and rider are “equally elegant.” Photo © Horses: Portraits by Derry Moore by Derry Moore, Rizzoli New York, 2016

“There was a lot of equestrian art and accessories and traditional English furniture to deal with,” Roberts says. In the living room, he placed a handsome old bronze of a horse on a contemporary étagère of his own design. “My whole approach was to mix their horsey things with contemporary art and furniture of other periods and styles,” Roberts says. “Loosening it up like this makes it not look like the gentleman’s bar at the club or a vignette in a Ralph Lauren store somewhere.”

It makes sense that in our technological age, photography has taken up painting’s mantle as a primary way of depicting horses — and the medium serves it well indeed, with the ability to capture with crystal clarity all the facets that make the animals appealing. New York photography specialist Robin Rice Gallery shows artists, like Patricia Heal and Pete Kelly, who often train their lenses on equines. Heal takes an empathetic approach to subjects like the inhabitants of the Dartmoor Pony Heritage Trust, in her native England. Kelly, meanwhile, prides himself on mixing the latest in digital manipulation with the most traditional of methods, such as the encaustic process that gives texture to his prints, thanks to the addition of a layer of wax.

Rizzoli’s recently released Horses: Portraits by Derry Moore is a handsome volume full of sensitive photographs of its titular subjects. The London-based Moore, who is the 12th Earl of Drogheda, had never trained his eye on horses before — he’s best known for posh interiors and portraits of the even posher humans who inhabit them — but the topic was suggested by an editor as a natural extension of his métier. The project took him to Louisiana, Kentucky, Spain, India and all across his native England. He notes that his personal horse-art touchstones include not only Stubbs but also The Surrender of Breda by Diego Velásquez and the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum.

“It’s their beauty, their character, their spirit, their relationship to man,” says Moore of the animal’s timeless appeal. “Looking at various representations of the horse in art — no two are the same. Each one has its own unique spirit and character.”

Whatever the medium or the pose, or even the arrangement of the works themselves, truly artful depictions of a horse will always win the day — and not just by a nose.