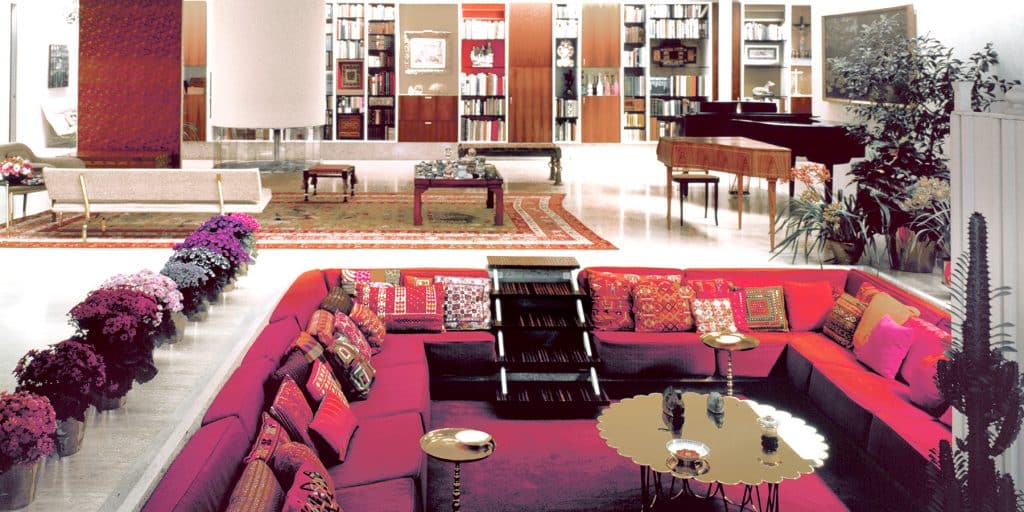

July 7, 2019The new Phaidon volume Herman Miller: A Way of Living takes a deep dive into the iconic American mid-century modern furniture company of its title. It features hundred of captivating photos, including this one of Charles and Ray Eames chairs from a 1964 catalogue. Top: The company’s head textile designer, Alexander Girard, designed a house in 1957 for J. Irwin and Xenia Miller in Columbus, Indiana (photo courtesy Miller House and Garden Collection, 1953–2009 [M003] Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Indianapolis, Indiana). All images © Herman Miller Archives, unless otherwise noted

Alexander Girard was in some ways the best advertisement for Herman Miller, the company whose textile division he helmed from 1952 to 1973. And in some ways, he was the worst.

The best because, with the colorful fabrics he designed, he made life in and around the Herman Miller headquarters, in Zeeland, Michigan, seem joyful. Most textiles used in offices then tended toward the utilitarian and somber, befitting the man in the gray flannel suit. “People got fainting fits if they saw bright, pure color,” he commented at the time. Girard, who was raised in Italy, changed that, creating more than 300 fabrics for the company, many of which ended up on pieces by George Nelson and Charles and Ray Eames, Herman Miller’s best-known furniture designers. His designs had a whimsical, folk-art-inflected style that has had lasting appeal. The proof is in the number of his textiles still sold by Maharam, a division of Herman Miller since 2013.

Girard was the company’s worst advertisement, however, because in his widely photographed and imitated house in Santa Fe, the focus wasn’t on Herman Miller furniture. A square white conversation pit with built-ins and cushions but no sofas or lounge chairs dominated the living room of the home he shared with his wife, Susan, for four decades. He recessed his TV in an adobe wall (along with a clock and a dog bed). And instead of a conventional dining table, he hung a plank of wood from the ceiling, although he did surround it with the Eameses’ molded-fiberglass chairs, perennial Herman Miller bestsellers.

In 1968, Julius Shulman photographed the Eameses in their Los Angeles home, Case Study House #8, which they designed for the magazine Arts & Architecture. Photo © J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Girard also famously installed a conversation pit in the living room of Eero Saarinen’s Miller House, in Columbus, Indiana (1957), considered a masterpiece of mid-century residential architecture.

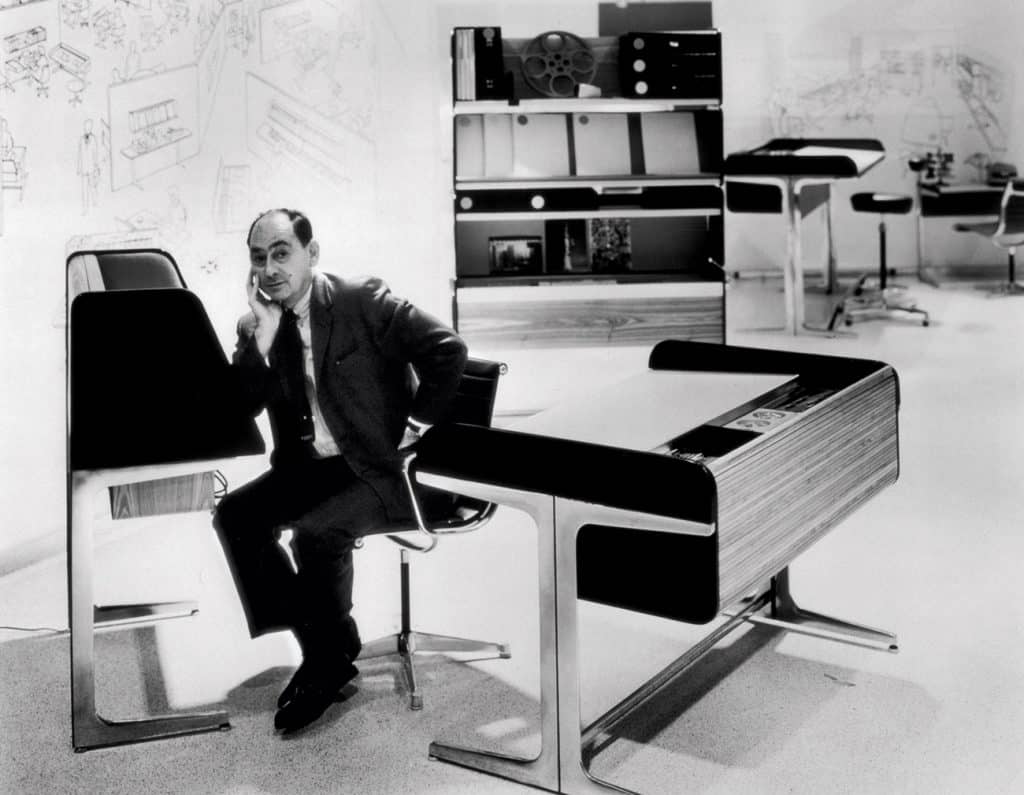

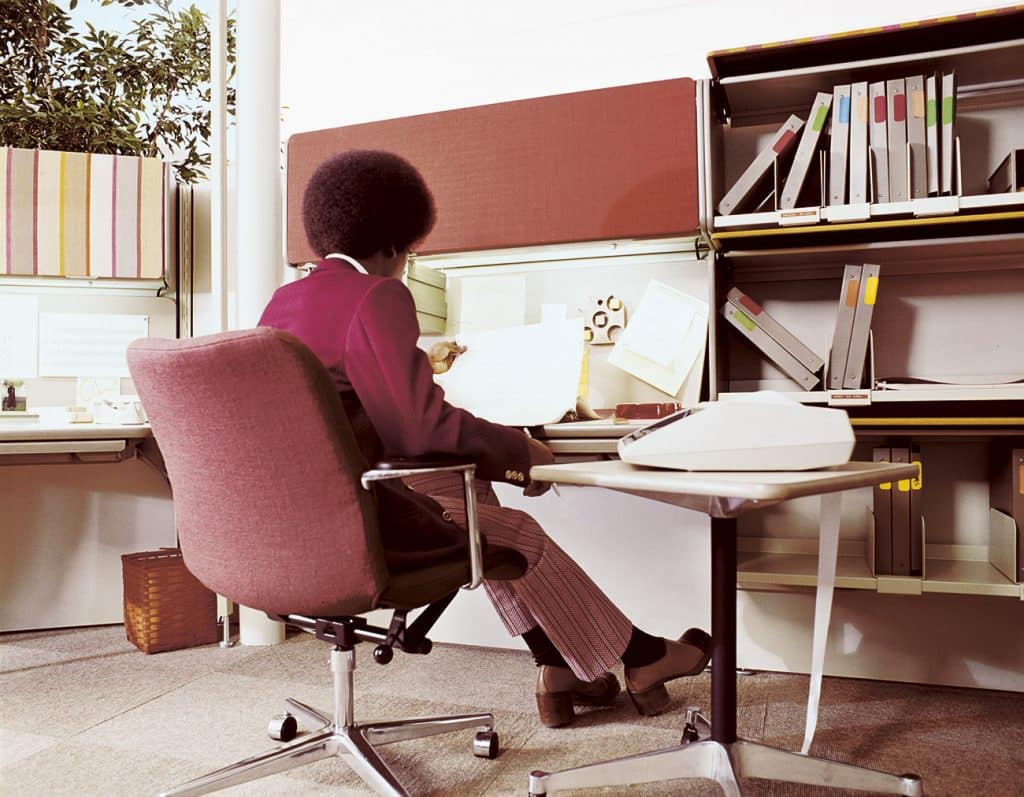

In this, he was simply reflecting the company’s evolving priorities. Herman Miller introduced an office line in the 1940s, and by 1968, outfitting workplaces had become its core business; it is even credited with inventing the cubicle (one of its early versions is for sale on 1stsdibs). Its relationship with residential furnishing was more on-again, off-again — at least until it acquired Design Within Reach, in 2014. That is one of the themes of Herman Miller: A Way of Living (Phaidon), a new book on the company edited by Sam Grawe, who until this year was the company’s global brand director; Amy Auscherman, its archivist; and the designer Leon Ransmeier.

Founded in 1905 as the Michigan Star Furniture Company, the outfit originally manufactured bedroom sets in traditional styles. But in 1930, the designer Gilbert Rohde persuaded then-CEO D.J. De Pree — who’d purchased Michigan Star in 1923 with his businessman father-in-law, the eponymous Herman Miller — to give modernism a try. The result was a range of streamlined dressers, night tables and headboards.

The Eameses’ now-ubiquitous lounge chair and ottoman was introduced in 1956 after years of experimentation. It has been in production ever since. Photo © Eames Office LLC

“Rohde was really hitting his stride in the nineteen thirties, before the war broke out,” Grawe says. “He visited the Bauhaus, he went to the Paris Expo in 1937, and he brought some of those ideas to the American interior.” Rohde died in 1944 and was succeeded as design director by Nelson, who, Grawe says, “was a genius but admitted that he stood on Rohde’s shoulders.”

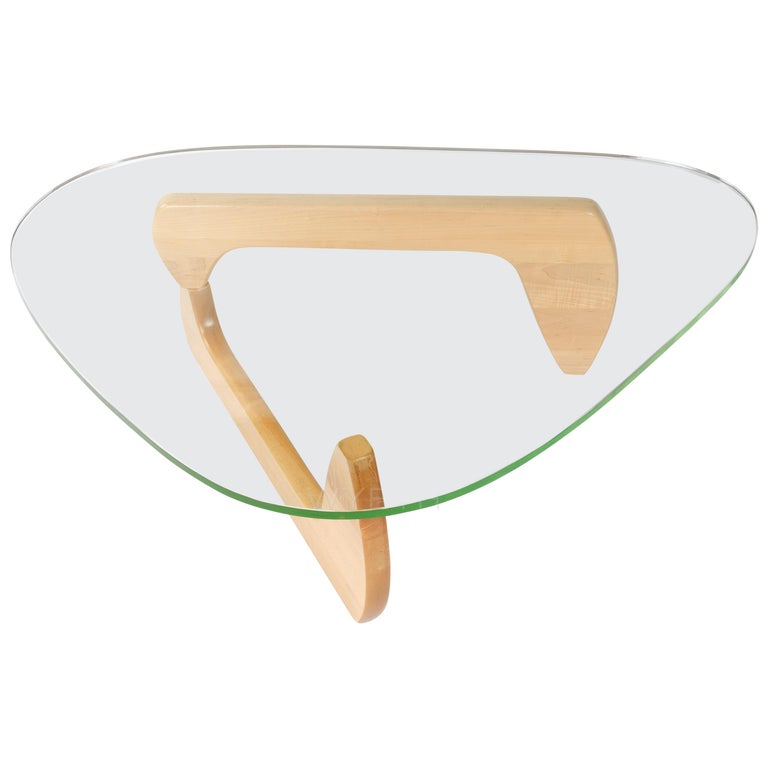

In 1942, the company, anticipating a postwar economic boom, began making office furniture for the first time. But it continued introducing pieces that were more likely to end up in the home. These included Isamu Noguchi‘s IN-50 coffee table, essentially a wooden sculpture under glass (introduced in 1947, discontinued in 1973 and reintroduced in 1984), and the famed molded-plywood and leather Eames lounge chair and ottoman (introduced in 1956 after years of experimentation and produced ever since). Even more decidedly domestic was the whimsical Marshmallow sofa, designed by Irving Harper, of George Nelson Associates, and introduced in 1956.

In the early 2010s, the company devoted time and resources to rethinking office culture and design in the age of the Internet, social networking and telecommuting. According to the book, the concept that resulted, now called Living Office, “posited that if creativity and ideas were to be the currency of business in the twenty-first century, then management methods, technology and tools, and places would all have to shift accordingly to facilitate a ‘naturally human’ experience of work.” Here, molded-plastic Eames chairs sit at a pedestal table by Nelson. The circular ottoman is by Girard.

Many Herman Miller products had crossover appeal. The outdoor pieces that Saarinen and Girard commissioned for the Miller House, for instance, became one of the company’s most famous office lines, the Eames Aluminum Group.

The playful poster created by Stephen Frykholm, Herman Miller’s first in-house graphic designer, for its annual picnic in 1970 won the American Institute of Graphic Arts’s annual competition that year.

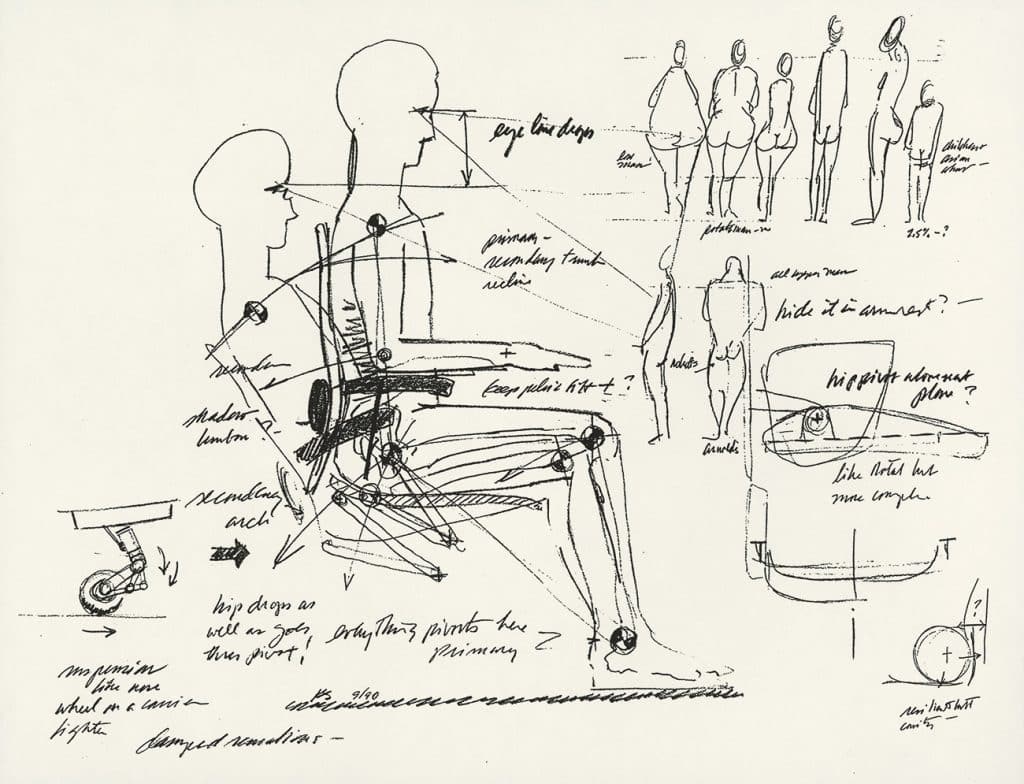

Conversely, the Aeron chair, introduced in 1994 as the ultimate in office ergonomics, is now its most popular residential product (according to Grawe), with telecommuting and the gig economy turning many homes into workspaces. But today, Herman Miller pieces meant for conference rooms and executive suites are just as likely to end up in living and dining rooms as in home offices, reflecting the attraction of well-made furniture for residents of a largely Ikea-furnished world.

In 2012, the company introduced the Herman Miller Collection, a series of new, domestically themed products. That launch dovetailed, the book explains, “with the company’s strategic shift toward being a lifestyle brand.”

And so, Herman Miller continues to introduce new home furniture, including a bedroom line by Michael Anastassiades and seating by Neil Logan. But it is still best known for its earlier pieces by the mid-century design greats.

A 1972 poster (seen here in a detail) promoted Herman Miller’s Environmental Enrichment Panels, designed by Girard. They were intended to enliven offices and other spaces with their bold patterns and colors. See our full article on many of these designs in The Study.

A single page in the 614-page book shows why. It reveals examples of the Eameses’ molded-plywood chair in disparate locations across three decades: under a Noguchi lamp in Georgia O’Keeffe‘s adobe house in Abiquiu, New Mexico, in 1965; overlooking the ocean in a Richard Neutra–designed house in Rolling Hills, California, in 1951; and surrounding a spectacular custom-designed Noguchi dining table in a house in Northeast Harbor, Maine, in 1948. Life magazine marveled that sales of the piece had “started slowly, then snowballed” until it was selling “at the remarkable rate of 3,000 a month” in 1950.

Even more remarkably, the company exceeded $2 billion in revenue in 2018 — a triumph, in part, of mid-century modernism. Says Auscherman, “While the bulk of the business is made up of office furniture sales, the residential pieces of George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard are what most people think of when they hear the name Herman Miller.”