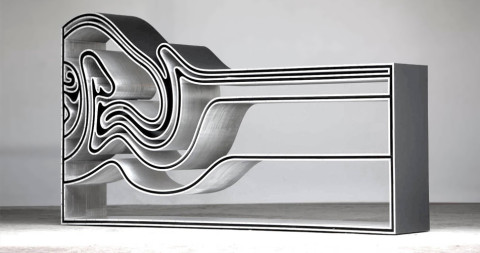

September 28, 2015“Ettore Sottsass: 1955–1969” at Friedman Benda in Manhattan spotlights furniture, ceramics and photographs produced during the formative years of the Italian designer and provocateur, whose 1968 cabinet for Poltronova stands near a window of the gallery (above).

The current exhibition, “Ettore Sottsass: 1955–1969,” at Manhattan gallery Friedman Benda will be a revelation to those who know the late iconoclastic Italian architect and designer only through his manufactured works, such as the snappy Valentine portable typewriter he designed for Olivetti in the late 1960s or his flamboyantly styled laminated furniture and lighting for the Memphis Group, from the early 1980s. There’s a sense of his personality conveyed by the brushstrokes on hand-decorated ceramics and his painted abstract compositions on the tops of custom side tables.

Even conventional furniture pieces by Sottsass bear his distinctive stamp, playing with color, form and scale in a way that anticipates his later postmodern designs. But the show also reveals much about the minds behind Friedman Benda. The single most striking item on view is a massive wall-mounted bookshelf and cabinet unit, designed by Sottsass in 1965 for an Olivetti executive. “We bought it ten years ago,” says gallery head Marc Benda. “But we waited until we could find many things from the period and show them together.”

Here’s the thing: 10 years ago, Friedman Benda did not exist. The gallery opened in 2007 — in Chelsea, the heart of New York’s high-end contemporary art market — and the long gestation of the new Sottsass show says much about the foresight of its principals. Now retired, Barry Friedman — a New York dealer with a career of more than 40 years in the modern-design market — surely brought the virtue of patience to the enterprise. And the young, Zurich-born Benda brought the creative vision.

Mobile Barbarella, a desk and cabinet from 1966. Photo by Adam Reich, courtesy of Friedman Benda and Ettore Sottsass Studio

With his gallery partner Jennifer Olshin, Benda has forged a program in avant-garde and contemporary design that features an international, multi-generational roster of talents. These include legends such as Sottsass and Wendell Castle, the studio design maverick still going strong at age 82; stars in mid-career like Dutch design guru Marcel Wanders and Brazilian brothers Fernando and Humberto Campana; and blossoming prodigies such as Joris Laarman of Holland and the members of the Japanese cooperative nendo. “Barry and Marc created a powerful platform for designers working today,” says Richard Wright, head of the Chicago auction house that bears his surname. “Their efforts have raised the bar for everybody in the field.”

A shared interest in Murano glass first brought Benda and Friedman together. In 1998, Benda was a student and small-time design dealer doing research in New York for Art Recovery. Needing cash, he showed the veteran dealer photos from his Venetian glass inventory and Friedman purchased a piece. (“And I was paid quickly, which was rare,” Benda notes.) Four years later, Benda joined Friedman’s gallery. Friedman had never shown contemporary work; aside from Italian glass, his particular specialty was French design of the 1930s and ’40s. But after Benda organized popular exhibitions of work by Sottsass in 2003 and London-based industrial designer Ron Arad the following year, Friedman fully trusted the younger man’s judgment. The gallery subsequently underwrote new work by Wanders, Laarman and the experimental Swedish group Front Design. In 2006, a successful pop-up show of designs by Arad, held in a Chelsea garage, Benda says, “gave Barry confidence that there was a clientele to sustain a contemporary design gallery.” And Benda was certain that design could hold its own with the art in neighboring galleries. “When you take design out of its domestic context and put it in a white box,” he explains, “it takes on a different meaning. It attains the kind of significance that artworks are allowed to acquire.”

Here, a Sottsass for Poltronova cabinet in Indian rosewood, ca. 1959, is topped by two vases from 1959. On the wall hang terracotta discs, each titled Offerta a Shiva (offering to Shiva), from 1964.

Friedman Benda showed art as well as design until this September. But Benda says the “two elements began to compete for time, space and money.” To remedy that, a new fine art gallery, called Albertz Benda and led by Thorsten Albertz (co-owner of the new gallery), has now opened in an adjacent space, dedicated to burgeoning talents and the work of under-recognized artists. Given the provocative new designs Friedman Benda will unveil this fall amid a chock-a-block schedule of events, it’s likely no one will miss the art. A new Wendell Castle show opens uptown this October at the Museum of Art & Design. Also that month, Friedman Benda will bring new works by Marcel Wanders, Paul Cocksedge, Misha Kahn and the Campana Brothers to the PAD London fair; in November, the gallery will present an all-encompassing environment by the Campana Brothers at the Salon: Art + Design showcase at New York’s Park Avenue Armory. And for this year’s Design Miami fair, the gallery plans to display the international breadth of its designer lineup, in a show with the working title “Five Continents.”

Their next exhibition in Chelsea is the kind of project dearest to the gallery principals’ hearts: entitled “Freeze” and opening October 29, it’s a showcase for new work by the young British designer Paul Cocksedge. For it, Cocksedge has created a group of tables made of copper and aluminum and crafted by pure physics. He froze the copper sections, causing the metal to contract by the tiniest fractions of a millimeter. He then fitted the copper pieces into the aluminum parts, and as the copper thawed, a seamless joint was formed, locking the two metals together. Other dealers might have told him it was too risky. “Our gallery is a platform for designers to attempt ambitious dream projects,” says Olshin, a deeply knowledgeable design expert who wears her scholarship lightly. “We try to foster even small kernels of ideas, especially when they speak to the imagination or to the impossible. We value prototypes because they manifest that initial spark. We’ve seen how an unrestrained foray can open a new chapter in design.”

As Olshin and Benda understand, it’s good to know design history, but even better when you can perhaps help write it.

TALKING POINTS

Jennifer Olshin of Friedman Benda shares her thoughts on a few choice pieces.