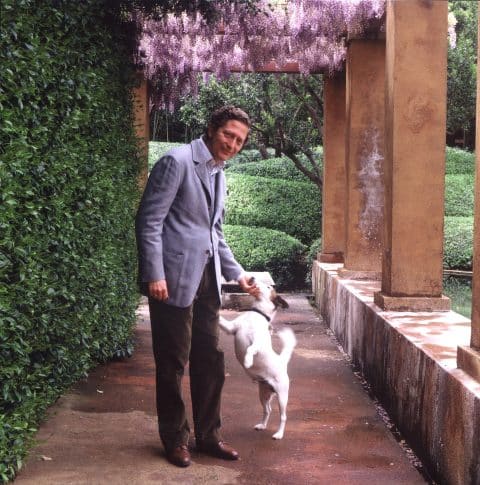

January 10, 2021For the past 40 years, Fernando Caruncho, a Spaniard who lives and works in Madrid, has been creating unforgettable landscapes. Instantly recognizable, a Caruncho garden is characterized by a strong geometric structure and features sweeps of contoured land, trees typically arranged in gridlike symmetry and large, rectilineal pools of water.

That his international profile is not as high as his talents merit may owe to the fact that he takes on very few projects each year and almost all of his work has been in Europe; his designs are particularly attuned to the strong light of Spain and the Mediterranean.

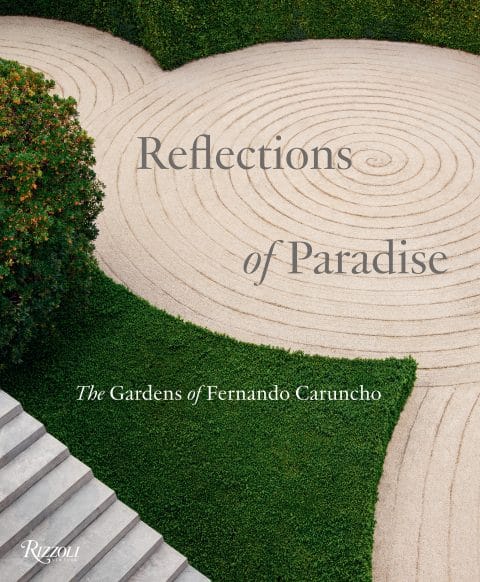

Now, with the publication of Reflections of Paradise: The Gardens of Fernando Caruncho (Rizzoli), Caruncho fans can admire many of his more recent projects. Among the book’s visual delights are a vineyard in Italy, a monumental golf-course garden in Morocco, a terrace garden bordered with laurel hedging at the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid and several sumptuous private gardens.

Caruncho is steeped in philosophy, having pursued that subject for three years at the Autonomous University of Madrid before switching to garden studies. When discussing his understanding of space and light, he frequently refers to philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, who both taught in their gardens; he also draws inspiration from Epicurus, the Stoic, who wrote, “It is impossible to know outside of the garden.”

Caruncho’s erudition extends to historic gardens in Europe and Japan, and he is fascinated by the different cultural conceptions of space and geometry. The book begins with a wide-ranging conversation between the English garden designer Gordon Taylor and Caruncho, who explains that he prefers to be called a gardener, not a designer, because a gardener is someone who nurtures an outdoor space rather than imposing a design upon it.

Backstopping his argument with history, Caruncho reminds us that the Alhambra was conceived and carried out by highly qualified gardeners who were masters of their art, that the gardens of Chinese and Japanese palaces were created by gardener-poets and that after completing the gardens of Versailles, André Le Nôtre was awarded the coveted title not of the king’s designer but the king’s gardener.

Next, Caruncho takes time to pay homage to William Kent’s 18th-century classical landscape garden at Rousham Park, in Oxfordshire; Filippo Brunelleschi’s magisterial architecture in Florence; the perfectly balanced layering of rocks and water at Katsura, the emperor’s garden in Kyoto; and the magnificent French garden that the great Le Nôtre designed at the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte prior to his work at Versailles.

He also reveals that he is no fan of the hugely influential Edwardian British garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, who, to his horror, was sometimes known to send clients a planting plan without having visited the garden site.

Jekyll is all about color and flowers, whereas Caruncho uses very few. Instead, his gardens are focused on structure, and he mostly restricts his palette, creating mass plantings of single specimens for which he selects plants that he believes connect a garden to its landscape, such as olives, vines, cypresses, holm oaks, lemons, limes, myrtles, palms, pines, figs, oleanders, camellias, hydrangeas, loniceras, jasmines and roses.

Mas de les Voltes, an agricultural property in the Spanish province of Girona, is the garden that, in 1994, first brought Caruncho some attention. Here, huge wheat fields, their edges angled and cut with sharp precision, function as a parterre in the landscape.

It is a garden of high drama, and many of the motifs employed — formal lines of cypress and olive trees set out in strict geometries, immense square troughs of water and vines planted on either side of long terraces — appear frequently in Caruncho’s later projects, including Mas Banyils, an agricultural garden in Catalonia; Cotoner, a wheat garden in Majorca; and Silva, a private garden on the outskirts of Madrid. All of these are profiled in the new book.

Caruncho has only undertaken three projects in the United States, including, most recently, on an island off the coast of Maine. In New Jersey, nearly 20 years ago, he was asked by the owners of Bird Haven Farm, Janet Mavec and Wayne Nordberg, to come up with a master plan for a series of gardens that would transform the existing fields and integrate them into the surrounding countryside, which he did using the geometry of a circle and an ellipse.

He had first deployed these shapes a few years earlier at a seaside property in Hillsboro Beach, near Boca Raton, Florida, where he created a garden around a house being designed by the distinguished Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta.

For Caruncho, this commission represented a key moment in his career, since, as he explains, it was the first time he moved away from using a squared grid. Instead he employed a series of three circles to extend the sweep of the house to the ocean and make a garden of terraced spheres that presents a bold contrast to the rigid angles of the house.

His inspiration, he tells us, came from Botticelli, Bosch and Dante, who all incorporated spheres in their work. Circles continue to define many of Caruncho’s projects — most dramatically in a private garden in Porto Heli, Greece, and in the garden surrounding his own Moorish-style studio in Madrid.

Caruncho describes his creative practice as a quasi-mystical poetic experience and stresses that his gardens are a search for simplicity and natural order. “The process of simplifying takes me through a labyrinth of complexity,” the philosopher-gardener says. “The more you simplify a garden, the more mysterious it becomes.