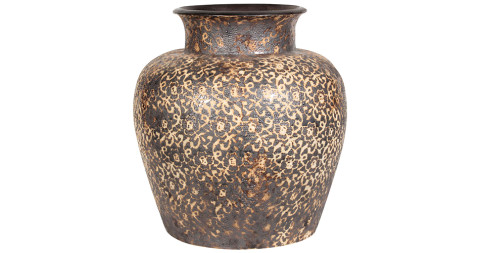

May 25, 2015In recent years, designer Donna Karan has expanded her aesthetic purview beyond fashion, collaborating with artisans around the world to creation furniture and home accessories that are now available through a 1stdibs storefront. All photos by Emily Andrews unless otherwise noted. Top: Tobacco-leaf vases, handcrafted in Haiti in collaboration with artisan Jean-Paul Sylvaince (photo courtesy of Urban Zen)

The 7.0-magnitude earthquake that devastated Haiti in 2010 left at least 100,000 dead and virtually wiped out the country’s essential infrastructure, including hospitals, transportation and phone service. Celebrities like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie as well as Haitian-born musician Wyclef Jean were quick to pledge money and lend their names to the cause of reconstruction. Though there was nonstop coverage on cable and the Web, Donna Karan was in something of a news blackout, sitting in a hospital with a sick relative. “What earthquake?” was her response when someone mentioned the catastrophe.

“I really did not know Haiti or understand Haiti,” she says on a cool March morning, sitting in the calm, airy loft she uses for meetings above her Urban Zen fashion and lifestyle store in New York’s West Village. But within weeks, the famed fashion designer was on a plane to the small island nation. Dressed in loose, drapey layers of black, as is her wont, Karan recounts how she thought she could help Haiti recover by seeking out its artisans. No matter their nationality, artisans, she says, “have always been my inspiration.” Expecting to encounter one or two craft specialties, she was startled to discover that Haitians were adept at a vast range of genres. “I realized what an endless array of objects there were,” she says, whether made of stone, textile, metal or recycled materials.

In the five years since, Karan has made it her mission to celebrate Haiti’s indigenous talents by using her clout to introduce their work to a wider public. And so, alongside the figure-flattering jersey dresses, leather leggings and geometric wooden tables artfully positioned around Urban Zen, which also has outposts in Sag Harbor and Aspen, one can find such Haitian products as woven handbags made of papier-mâché strips and minimalist vases wrapped in dried tobacco leaves — traditional handicrafts re-imagined by Karan’s own inimitable eye. Now, Karan has partnered with 1stdibs to extend Urban Zen’s reach even further.

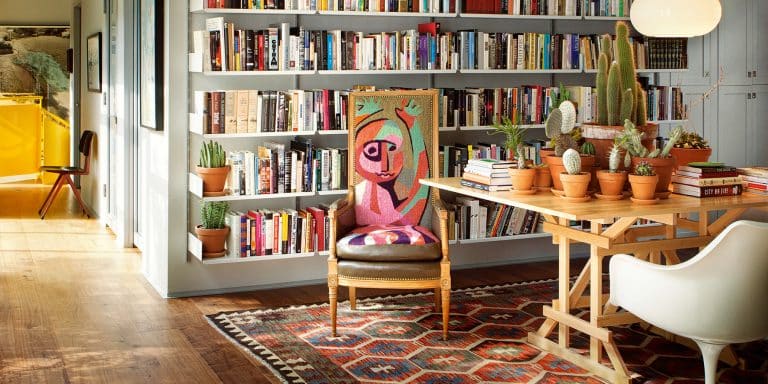

In Karan’s Urban Zen shop in New York’s West Village, an antique Balinese brass gong hangs above hand-poured Celine Cannon candles and Caribbean Craft papier-mâché woven bags.

In Karan’s Urban Zen shop in New York’s West Village,

Urban Zen evolved in the years after Karan’s husband, artist Stephan Weiss, died from cancer in 2001. Her determination to dedicate his grand studio space on Manhattan’s Greenwich Street to a worthy cause initially begat a 10-day conference on how to change the world through health care, education and culture. “There was no ‘care’ in ‘health care,’ ” she says, noting that the nonprofit wing of Urban Zen has developed initiatives incorporating yoga and other alternative-medicine techniques to help patients and health-care workers alike. Next came the concept for the store, which occupies part of the first floor. A portion of sales from select categories funds the Urban Zen Foundation, which also relies on private and corporate donations, as well as Karan’s personal philanthropy. “Everybody knows there’s a story behind the objects,” she says, “and that’s the beauty of it.”

Karan’s charitable urge is matched by her passion for travel. Before Haiti, there was her first love: Bali. So enamored was she of the Indonesian island when she first visited more than 20 years ago that, she recalls, “my husband and I really wanted to move there. It touches my heart.” With her thriving fashion company headquartered in Manhattan, however, Bali was not the most practical option. So instead, after Weiss died, she constructed a house on land they had acquired in Parrot Cay, in the Turks and Caicos islands. Nonetheless, the house was fabricated primarily in Bali and shipped to the Caribbean, as was the Balinese furniture Karan designed with architect Dominic Kozerski of Bonetti Kozerski Studio: heavy, low-slung pieces in simple shapes solidly constructed of teak. “It was a place I built for my family to be together,” she explains.

“Everybody knows there’s a story behind the objects. And that’s the beauty of it.”

Throughout the space, artisanal pieces accessorize looks from the brand’s current fashion collection.

Karan decked out her Manhattan apartment and Hamptons getaway in a similar vein and soon heeded calls to turn her vision into a collection. Her signature sofa doubles as a bed, with a long, plump, monochromatic cushion resting on a teak platform, which extends beyond the cushion, creating a surface space for books or a cup of tea. “It’s your table, it’s your bed, it’s anything you want it to be,” Karan says. There’s a massive beanbag, which she playfully describes as “all you need in life,” and big wood dining tables with benches. Many of her key pieces can now be found on 1stdibs. “It’s minimal and soulful at the same time,” she says of the aesthetic. “It really embraces both. The size is something that says, ‘Wow,’ but it does not say, ‘Do not touch me.’ It says, ‘Lay on me, be with me.’”

Designing furniture offered clear appeal for one of America’s most accomplished fashion designers. The daughter of a haberdasher, Karan began her career working for Anne Klein, a major force in American sportswear. When Klein died in 1974, Karan took charge of the atelier, along with Louis Dell’Olio, before starting her own namesake collection in 1984; women today can thank Karan for envisioning a way of dressing that’s professional and functional while at the same time feminine, and even sexy. In 2001, Karan sold the business to French luxury conglomerate LVMH, but she remained in control of the creative vision. “Anne taught me when I was very young: She said, ‘You know, Donna, designing a toothbrush is the same as designing fashion.’ It touches us, in different ways. Obviously, [my furniture] looks like my clothes. It’s a signature style.” Indeed, it’s sensual in a relaxed, not-trying-too-hard way, just like her clothes.

The Balinese crafts on offer from Urban Zen include an antique beaded headrest, as well as bracelets made of teak and shell. Photo courtesy of Urban Zen

Karan still finds it thrilling to collaborate with the Balinese artisans who produce the furniture she designs. When one of her team joins the conversation at Urban Zen and teases that she was so bored on a recent visit to Indonesia that she sat in the car while Karan happily spent the entire day working with the furniture-makers, Karan retorts, “How can you not get off on these planks of wood? I mean, they talk to me. This is what I love.”

When Karan began working with them, the Balinese artisans were further along in translating their techniques for international markets than their Haitian counterparts, who, Karan says, required a little more coaching. “I would work directly in the artisan set-ups,” she says. “I have to get involved.” In some cases, such as the tobacco-leaf vessels, Karan says she merely tinkered with silhouettes. But while visiting Christelle Paul, a group of craftsmen who make jewelry and votive candleholders from cattle horn, working with no roof over their heads in the “middle of nowhere,” she says, “I would sit with them and tell them when to stop the patina.”

Getting the right finish was even trickier for the talented metal-worker she found. “I couldn’t stand the patina,” she says. “It was all shine, shine, shine. I said, ‘Why can’t you get me that patina?’ Because my husband did sculptures in metal, I’m used to patinas.” It took two years, but finally he was able to dull the surface to the more raw, natural look — the “Donna patina” — she craved for intricately patterned trays and vessels.

“I would work directly in the artisan set-ups,” recalls Karan, in her studio above the shop, which is filled with furniture of her own design. “I have to get involved.”

Another ceramic Thai vase tops a Balinese teak-root console, with portraits by William Coupon of a Penan chief in Borneo (left) and a grandmother in New Guinea.

Sometimes she used her design expertise to work with artisans to create color stories, just as she does for her fashion collections; other times her experience proved useful in determining how to apply the artisans’ skills. Haitians are well-known for their papier-mâché masks, but there’s not a large market for masks in the U.S. “I said, ‘Instead of papier-mâché masks, what about papier-mâché handbags?’” she says. The results hold their own against haute design. Karan’s daughter, restaurateur Gabby Karan de Felice, even put Urban Zen’s crystal-and-wrought-iron chandeliers in her popular Hamptons and Tribeca boîtes, Tutto Il Giorno. The oversize, circular chandeliers, made in Port-au-Prince by Karine Faubert Villard, who goes by “Cookie,” look right at home with the cement walls and reclaimed-oak floors of Belgian-born architect Francis D’Haene’s modern-luxe decor.

Initially, Karan was traveling to Haiti monthly or more; now she visits three or four times a year. But her plans are no less ambitious. Karan created an art center for children in Port-au-Prince and is about to open the Urban Zen Vocational Center for Artisans, for continuing education, in the capital. People may associate her with New York, but she says the city is really just about work for her: “I live in the world.”

Lately, she has worked on some new products in Thailand, and she hopes soon to fit in trips to Papua New Guinea and South America — “which I’m embarrassed to tell you I’ve never been to,” Karan says. “My dream is to be in all developing countries. So this is just the beginning for me.”