The field of contemporary design may be entering a kind of Golden Age right now, with an exciting new generation of creators taking the world of bespoke, handcrafted furniture and lighting in fresh and unexpected directions. Yet the past is still present: Connoisseurs continue to turn to antiques as well as classic pieces of 20th-century design that have a timeless quality, feeling as relevant today as they did when they were made. Designers, too, constantly look to the past for ideas, materials and techniques. As 1stdibs delves ever deeper into this burgeoning collecting category, Introspective asks 11 accomplished young makers about the pieces from the past that set their imaginations ablaze.

November 7, 2016To celebrate the debut of 1stdibs contemporary-design division, Introspective spotlights notable young creatives — including, above from left, Alex Rosenhaus and Drew Arrison, of Alex Drew & No One — and asks them to discuss the legendary makers and vintage periods that most inspire their work. Portrait by Julien Roubinet, all other photos courtesy of Alex Drew & No One

Alex Drew & No One

Detroit

When Alex Rosenhaus and Drew Arrison met in New York several years ago, Rosenhaus was building high-end custom furniture at Walter P. Sauer and Arrison was working in a model-making shop building elaborate sculptures for corporate advertisements and artful window displays for the likes of Tiffany & Co.

They both yearned to make pieces drawn from their own ideas. So when they started working together, in 2012, they named their company Alex Drew & No One. In their work, they take Rosenhaus’s expertise in Old World materials and techniques and apply it to modern furniture.

The sinuous base of their Lily table, for example, is gilded in 23-karat gold, in the French style, as are the intertwined geometric legs of their Golden Blaze dining table. Designer Karl Springer had a similar approach, Rosenhaus says, gilding every inch of sleek modern chairs or covering them entirely in leather. “He was known for using exotic and extravagant materials,” she adds, “like parchment, shagreen, leather, mother-of-pearl, furs — you name it — many of which we also love.”

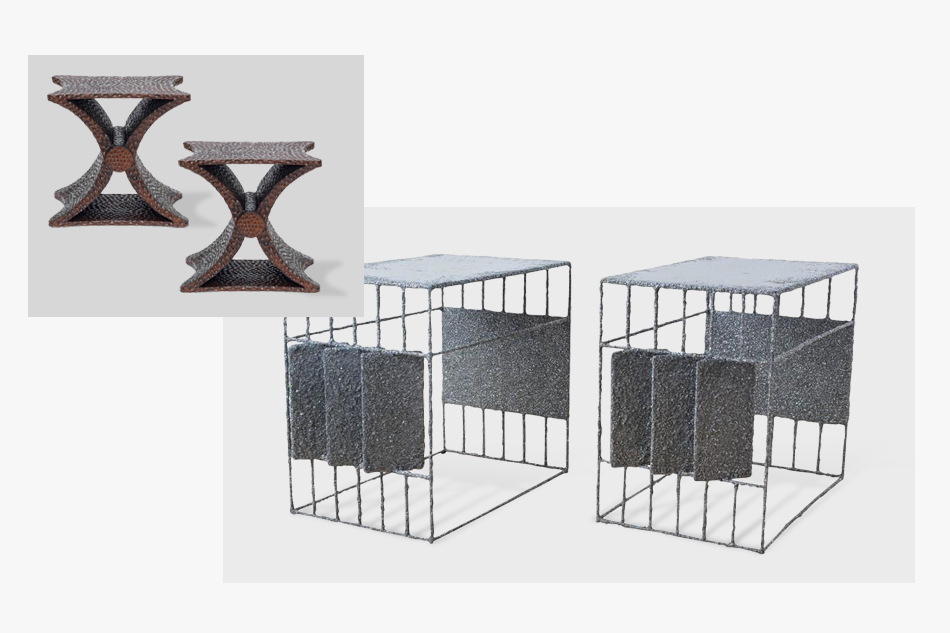

Samuel Amoia started making furniture a few years back for his interior design projects. He poses here with a drum table made of African blue sodalite stone and white plaster. Behind him is a side table encrusted with crushed malachite from Africa. All photos courtesy of Samuel Amoia

Samuel Amoia

New York City

Interior designer Samuel Amoia has worked with real-estate heavyweights Ian Schrager and André Balazs, as well such fashion brands as Dior and Stella McCartney. A few years ago, he started producing bespoke furniture for his interior design clients — simple pieces with humble materials, such as drums made of salt, sand or cement. These designs caught on like wildfire, and requests began pouring in.

The aesthetic of the French designer Jean-Michel Frank guides his work. “I think he is the greatest designer of the twentieth century,” Amoia says. “His work is incredibly understated and restrained. He used sumptuous materials, like straw marquetry and brass, and really let those materials be the star.”

Amoia’s work has become more elaborate in the past year or so. He began finishing geometric tables with crushed or shaved materials, such as malachite, aluminum and pyrite, which adds textural, sometimes glittery, effects. But he still follows Frank’s lead in his respect for materials: “I’ll never dye salt or sand. If I’m using red jasper, I want it to look like red jasper. Keep it honest. Keep it pure.”

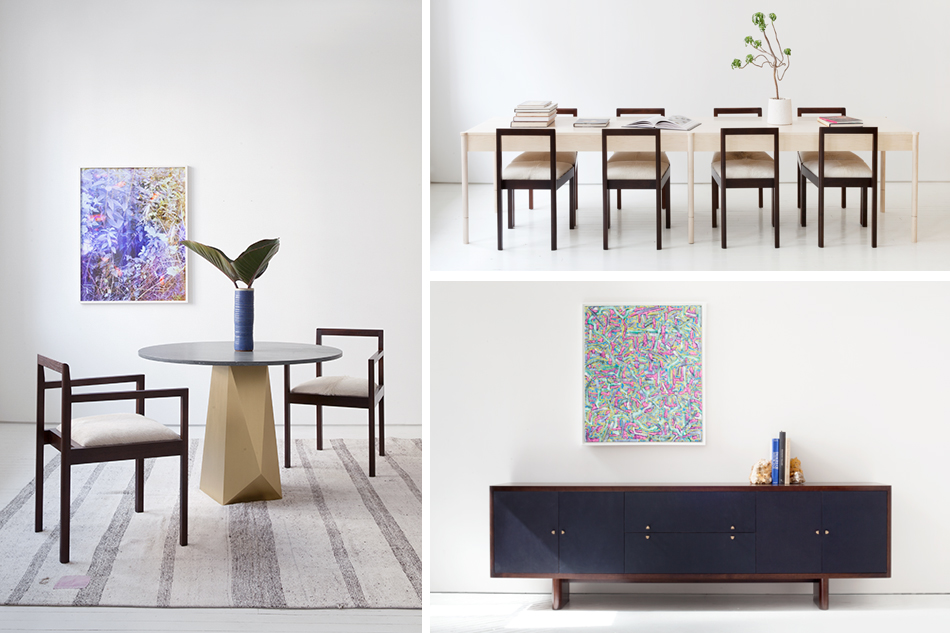

The three partners behind Egg Collective — from left, Hillary Petrie, Stephanie Beamer and Crystal Ellis — met studying architecture at St. Louis’s Washington University and started their furniture and lighting company about 10 years later. Portrait by Jason Rodgers, all other photos by Hannah Whitaker

Egg Collective

New York City

Stephanie Beamer, Crystal Ellis and Hillary Petrie studied architecture together at Washington University in St. Louis, before splitting off in different directions: Beamer became an apprentice to a fine-furniture maker, Ellis earned an MFA in sculpture at the Rhode Island School of Design, and Petrie worked at a fabrication shop in New Orleans.

Roughly a decade later, they reconnected to combine their different backgrounds in a furniture and lighting venture they called Egg Collective. For inspiration, naturally, the three turned to an architect: Oscar Niemeyer, whose buildings and furniture reflected “the free and sensual curves” of the mountains in his native Brazil. Similar curves show up in Egg Collective’s Pete & Nora floor lamp, Feehan mirror and other pieces. More important, the designers take Niemeyer’s approach to heart. “His pieces, like the Alta chair and Rio chaise lounge, were meant to be in the middle of a space, seen from different angles. Their look transforms depending on your vantage point,” Ellis says. “That’s a sculptural idea we’re constantly thinking about.”

Rhode Island School of Design graduate Debra Folz founded her eponymous studio five years ago, creating highly modern work that incorporates traditional sewing and embroidering motifs into mirrors, tables and more. Portrait by Joel Benjamin, all other photos by Erin Yamagata and styled by Chloe Daley, unless otherwise noted

Debra Folz

Providence

Debra Folz has fond memories of growing up sewing and embroidering, so naturally she wanted to incorporate those traditions into the design studio she founded about five years ago. Her Braided tables, for example, are made of New England wood, their edges adorned with leather strapping inspired by the traditional braiding on primitive tools. Her Sewn Surfaces mirrors, meanwhile, are designed to look as if they’d been stitched to the wall with brass or nickel.

“It’s interesting to me to take textile traditions, which are perceived as feminine and delicate, and try to modernize them,” says Folz, who earned an MFA in furniture design from the Rhode Island School of Design. “Those traditions can have a softening effect.”

For inspiration, she constantly turns to the Spanish architect Patricia Urquiola, who is well known for adding textile-like touches to her furniture pieces for Cappellini and Moroso, such as the Smock armchair and the Klara rocking armchair. “I admire her as a practitioner, too,” Folz says. “She’s navigated her career brilliantly, and the scale of her projects — hotels, retail spaces and the like — is impressive.”

Elyse Graham began making her plaster vessels after earning a degree in art semiotics from Brown and then launching her own jewelry business. Portrait by Maria Schriber, all other photos by Peter Bohler

Elyse Graham

Los Angeles

Elyse Graham crafts vases that are inspired by geology: striated stones, glacial erosion, metamorphic rock. Graham, who studied art semiotics at Brown University and previously had her own jewelry business, begins her bulbous forms by swirling liquid plaster around within an inflated balloon, lining the interior with a thin layer of the viscous white material. After the plaster has dried, she removes the balloon, cuts an opening into the top of the vessel, then coats the inside with resin, which, she says, “drips out to form little stalactites” along the rim. Finally, she dip-dyes the outside of the vase, layer by layer, causing wavy lines to appear on the plaster’s undulating surface.

The result is a completely unique piece that celebrates the effects of time’s passage. Graham points out similarities between her vases and weathered 19th-century French Biot pots, which were used to store oil in Provence and are characterized by irregular glazes around their mouths. “I love the erosion of time that they convey,” she says.

Canadian architect brothers-in-law Scott Richler (left) and Gabriel Kakon teamed up to launch their gem-inspired lighting design company, Gabriel Scott, in 2012. Portrait by Max Abadian

Gabriel Scott

Montreal

If the Harlow chandelier by the duo Gabriel Scott resembles a collection of gems, the parallel is intentional. Cofounder Scott Richler spent years designing jewelry, and he brought that sensibility with him into furniture design when he teamed up with his brother-in-law, Gabriel Kakon, in 2012. In the asymmetrical chandelier, mold-blown glass forms inspired by the cuts of gemstones are held in place by metallic prongs that mimic settings.

Their work is inspired, in part, by vintage Repossi jewelry from the 1970s, like the house’s necklace with an engraved emerald, diamonds and rectangular gold links. “Alberto Repossi was from an old family of jewelry makers going back hundreds of years,” Richler explains, “but the company always added modern elements, like a bold, architectural use of gold.”

Through his company, Jace Will Design, Jason William McCloskey shows off the skills he acquired as an apprentice to a Scottish furniture maker, who taught him 18th-century English woodworking techniques. He poses here with his You lounge chair. Portrait by Matthew Staver, all other photos courtesy of Jace Will Design

Jace Will Design

Denver

The seat of Jason William McCloskey’s Wing chair, made of one piece of laminated and bent wood, has such a deep curve and such tall sides that it looks as if it’s about to fly away. “People think it’s about a bird,” says McCloskey, who has more than 20 years of woodworking experience under his belt, “but it’s actually about the solitude that you find in a canyon.”

He discovered the emotional power of such natural wonders in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, where he once led canyoneering trips for Outward Bound. Nature is almost always the jumping-off point for his sketching, but he gained his facility with furniture proportions — making the legs of a chair just the right height, for example — as an apprentice to a Scottish furniture maker. During that apprenticeship, he spent three years learning 18th-century English woodworking techniques, building Queen Anne sofas, Gainsborough chairs and Chippendale cabinets. The skills he acquired are crucial to his process today. “If I could make those things,” he says. “I could make anything.”

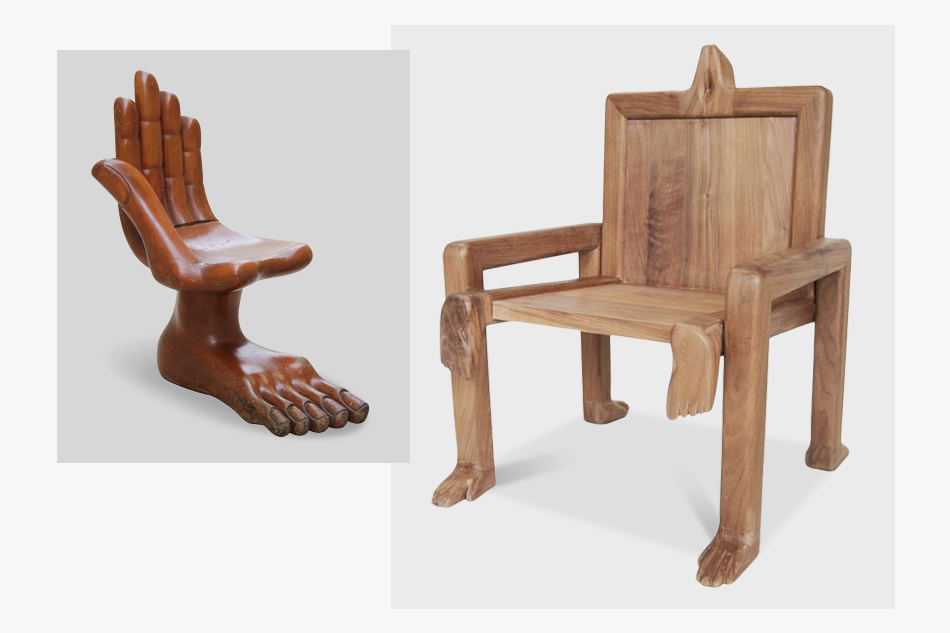

Material Lust cofounders Lauren Larson and Christian Swafford — a couple in life — consider themselves as much artists as designers. Their Khnum table lamp sits to the left. Portrait by Evan Miller, all other photos courtesy of Material Lust

Material Lust

New York City

Lauren Larson and Christian Swafford, cofounders of Material Lust, aren’t sure whether to call themselves designers or artists. The couple studied design in college and worked for high-profile interior designers —Larson at Victoria Hagan, Swafford at Studio Sofield — but they were also deeply influenced by their mothers, who were both painters. Their company, which they started in 2013 and which makes its Los Angeles debut this month at J.F. Chen, “is a creative outlet, allowing us to go back to the roots of our art upbringings while also using our design training,” Larson says.

The result is artisan-made furniture that’s playfully, sometimes hauntingly, surreal. Their Cabra oak stool has wavy legs, giving it a dreamlike quality; their Crepuscule lamp looks a bit like a simplified, monochrome insect sprouting many limbs. For inspiration, the couple often looks to the Mexican sculptor and painter Pedro Friedeberg and his famous chairs, tables and candlesticks shaped like hands and feet. Larson and Swafford adopted that motif for their Crawl children’s chair, which is made of hand-carved walnut and has a folk-art aesthetic.

While working for the World Bank, Elizabeth Parker noticed the complicated relationship members of some West African communities have with the idea of home. This insight led her to complete an MFA in interior design at New York’s Parsons and then to found her furniture company, ParkerWorks. Portrait by Jen Lewandowski, all other photos courtesy of ParkerWorks

ParkerWorks

Portland, Oregon

Elizabeth Parker found her way into design from an unlikely place: the World Bank, where she worked as a political-risk analyst examining West Africa. “I was doing real-time crisis response for the Bank’s international staff and looking for future political instability. I spent a lot of time thinking about people in West Africa and their homes, how they aren’t really protected by them, and they might need to leave if there’s political violence or an earthquake. So I became attuned to the emotional terrain of interiors and how we attach ourselves to them,” she recalls.

That insight led her to earn an MFA in interior design at Parsons School of Design, and to learn how to handcraft furniture from wood, concrete and other materials. The resulting creations are meditations on loneliness and imperfection. Her Funny Buddy floor lamps, for example, feature wonky, hand-cast concrete cap pieces, which she calls “noggins,” atop a tripod of spindly brass legs. “They’re intentionally made to look like little friends that live with you, which makes people laugh,” she says.

Parker finds anything handmade and embodying wabi-sabi — a Japanese aesthetic embracing transience and imperfection — “utterly compelling.” She cites a set of four 17th-century Spanish cork buoys that she recently found on 1stdibs. “From a distance, they are simple forms. But up close, there’s all this incredible texture, stitching, dimension and color,” she observes. “And each one is juicily out of sync with the next.”

Yale School of Architecture–trained husband-and-wife duo Oliver and Jean Pelle collaborate on each of the pieces of lighting and furniture created by their company, Pelle. An example of their X-Tall Bubble chandelier hangs behind them. Portrait by Daniel Seung Lee, all other photos courtesy of Pelle

Pelle

New York City

Husband-and-wife team Oliver and Jean Pelle met as graduate students at the Yale School of Architecture. Accordingly, they approach design as architects, with a laser-sharp focus on form. The Pelles often use computers to engineer technically complex pieces, like their modular Pris Major and Pris Minor chandeliers. But part of what drew Jean away from architecture and into design is what she calls “the softer things” — evocative materials that can give objects a sculptural feel.

She names as an influence Frank Gehry’s Easy Edges series, made of rough cardboard that becomes pliant and supple over time. For Pelle’s flower-shaped Lure sconces, Jean creates the cast-paper petals by hand, giving every one a realistic, velvety texture. Instead of being lit from within, the flower is spotlit by a suspended LED — a surprisingly modern feature that was Oliver’s contribution. “Each piece is a balance between our two personalities,” Jean says.

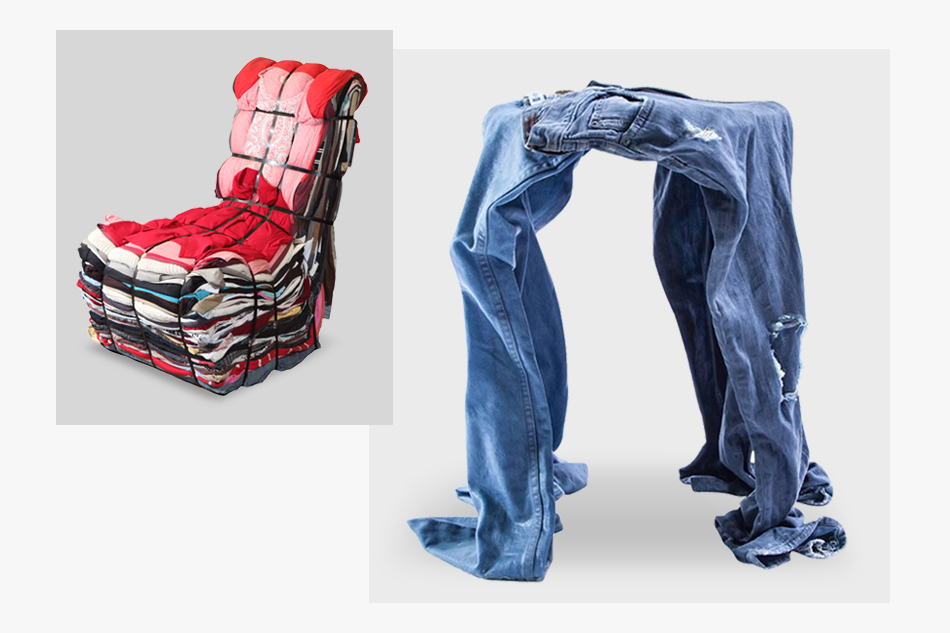

Turkish-born Pratt Institute graduate Vedat Ulgen named his company Thislexik to celebrate the way his dyslexia allows him to see the world differently — something his furniture helps others do, as well. Portrait by Eda Durust, all other photos by Allyson Lubow

Thislexik

Brooklyn

In Vedat Ulgen’s one-of-a-kind Worn stools, old pairs of jeans appear to float magically without supports; in fact, he’s made them rigid with the help of resin. The 28-year-old Pratt Institute graduate has an insatiable drive to create furniture that makes people question, and interact with, their surroundings. (His company’s name pays tribute to his dyslexia, which he says helps him see the world differently.) His Arc light, for instance, allows the owner to reposition a long LED bulb within a sculptural wooden wall panel.

Ulgen, a native of Turkey, draws inspiration from the Dutch design collective Droog, which has also made chairs from clothing and once sold an unconventional DIY chair that owners had to shape themselves by taking a sledgehammer to an aluminum box. “They make you feel and experience the moment, and that’s what I try to do with my designs,” he says.