Concrete may be ubiquitous in the sidewalks beneath our feet and the foundations of our houses, but this deceptively banal material — a mixture of cement, gravel, sand, water and broken stone or gravel — has long been a favorite among minimalists. Brutalist architects, including Marcel Breuer and Paul Rudolph, were concrete fiends, and trailblazers like Willy Guhl and Giovanni Offredi were shaping the weighty substance into graceful furniture as early as the 1950s.

Now, a new generation of designers is taking this medium to new heights: turning it into textiles, coloring it to painterly effect and juxtaposing it with traditional techniques and found objects. Below, Introspective examines six creative heavyweights who are pushing the limits of concrete.

Lee Hun Chung

June 27, 2016Lee Hun Chung combines raw concrete and glazed ceramic in his artful furnishings. Portrait courtesy of Seomi International

For Lee Hun Chung, concrete literally feels like home. Trained in architecture as well as art, he designed his own house, located an hour from Seoul, as a bright and boxy concrete structure, which he completed in 2004. “From that moment, I fell in love with the material,” says Lee, who has exhibited his art and furniture worldwide since the early ’90s. “I like concrete’s solidness. It has brute force.”

He softens this punch by combining it with glazed ceramic: A concrete coffee table has a knobby, deep-blue ceramic base; a concrete bench is supported on one side by a clay globe. (These and other works can be found at Seomi International, in Los Angeles.) Lee fashions the ceramic components by mixing his own clay and firing it in a brick kiln he built himself and fuels with pinewood. He colors the pieces with celadon glaze — a finicky, centuries-old technique that originated in Asia — so that the surfaces have subtle cracks and resemble abstract paintings. Although he sometimes uses just one material, his favorite works bring together concrete and ceramic, mixing modernity and tradition in a way that has appealed to many collectors. “It’s a sophisticated combination,” Lee says, “and I like the harmony.”

JAMESPLUMB

Designers James Russell and Hannah Plumb of London’s JAMESPLUMB create works that combine concrete forms with antique furniture. Portrait by Sharyn Cairns

London-based designers Hannah Plumb and James Russell are known for meticulously reinventing pieces from the past. The married couple, who work under the name JAMESPLUMB, once ingeniously made chests of drawers using repurposed vintage suitcases, for instance. Their fascination with concrete began when an antique wooden chair broke during a dinner party. “The chair became even more beautiful, still standing with only three legs, a cracked frame and new negative space,” recalls Russell.

They wanted to make the seat functional again “without unraveling its fragility” and discovered they could cast concrete to fit perfectly inside the frame. The result was a series that married antique furniture with concrete and was displayed in the solo exhibition “From This Day Forward,” at the cultural space Zona K, in Milan, in 2010. “Each piece is named after marriage vows, a celebration of two distinct entities becoming one while retaining their individuality,” Russell says.

Years later, Russell and Plumb are still working with concrete. This past January, Slete Gallery, in Culver City, California, exhibited their recent series “Settle” at the FOG Design & Art Fair in San Francisco. This time they’ve combined concrete with, among other materials, antique oak and pine church pews. They describe the collection as “a balance between surreal and solid.”

Amelie Marei Loellmann

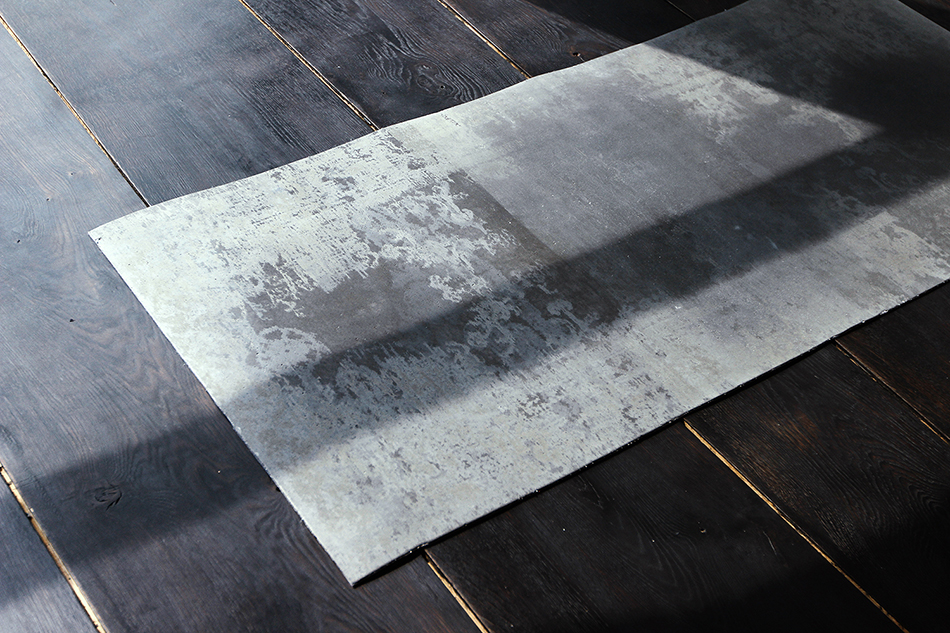

German artist Amelie Marei Loellmann transforms concrete into flexible textiles, including clothing and rugs. All photos courtesy of the artist & BUNDER/BRAEM

Confounding as it may sound, Amelie Marei Loellmann uses concrete to create carpets and other pliable textiles. It all began a few years ago when she was studying fashion design at the Weissensee School of Art, in Berlin, and produced a final project that was inspired by construction materials. “My idea was to bring our surroundings to the body,” Loellmann explains. So she fashioned a concrete skirt, hat and bag; most of the collection was rigid, although all the pieces were relatively lightweight. Gradually, she developed a painstaking process for making concrete bendable, which begins with mixing her own fine compound and making an ultrathin cast around a fiber base.

When the concrete dries, Loellmann breaks it up to foster flexibility, then, finally, she sands and polishes the surfaces to make them shiny and soft to the touch. Her carpets, sold by Bunder/Braem in Berlin, are no more than two or three millimeters thick, although they are heavier than a typical rug. She has also made a curtain, to exhibit in a German museum, and last month she put a few of her concrete furnishings in a room she created for de Meldkamer, a project space established by her brothers, Jonas and Valentin Loellmann, in the Dutch city of Maastricht. “To me, concrete is a metaphor for thinking,” she says. “I don’t like to stay in heavy patterns. I prefer to follow my fantasy.”

Fernando Mastrangelo

MMaterial founder Fernando Mastrangelo casts sculptural furnishings in cement, the main ingredient in concrete, often layered with rock salt, crushed porcelain and sand. Top: The pastel gradations of Mastrangelo’s Fade series recall geological samples. Portrait by Cary Whittier

The Brooklyn-based designer and owner of MMaterial, Fernando Mastrangelo, made a name for himself by casting natural materials, such as sugar and salt, into sculptures. One of those works is Avarice, an Aztecan stone calendar that he made with cornmeal and adorned with carvings of corn-based products. The 2008 piece, now in the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum, was intended to draw attention to the mass cultivation of corn in his native Mexico.

His sculptural furniture is less political and more atmospheric, although the pieces also employ natural materials cast on metal supports. In recent years, he began working with a type of cement (the base ingredient of concrete) composed of a very fine powder, casting it to form tables, benches, desks, couches and chairs. “It can be made any color. There are no restrictions,” says Mastrangelo, who creates burn lines by pouring a layer, curing it and then pouring another. “Those lines make the piece feel like a living thing,” he muses.

It’s no surprise, then, that his pieces are inspired by the natural world. In his latest collection, Drift, a bench made of cement and sand resembles a rock formation, with an ombre-blue color scheme inspired by the glaciers of Patagonia and layers meant to evoke the Grand Canyon.

Mathilde Pénicaud

Mathilde Pénicaud‘s pieces spotlight steel as well as concrete, giving new purpose to common construction materials. All photos courtesy of Mathilde Pénicaud

As with Lee Hun Chung, Mathilde Pénicaud’s interest in concrete began with a building. More than a decade ago, she was renovating an old barn in the French countryside, which would become her studio, and the concrete she used sparked something inside her. “Concrete and steel are intimately linked in architecture, but the steel is hidden. I was curious about bringing this hidden structure to the surface,” says the artist, who has exhibited her work in Europe and North America since 2003 and is represented in New York by Twenty First Gallery.

With a background in metal sculpture, which she studied in Paris at the National School of Applied Arts and Crafts, Pénicaud builds steel frameworks for side tables, consoles, vases and lamps, often with undulating ridges that resemble twisting tornadoes or coiled snakes. She then casts concrete inside the ridges. “The steel is the skeleton, and the concrete is the skin,” she explains. The results can look sinuous, geometric, or even like idiosyncratic crystals protruding from the wall of a cave. “When I began doing furniture, I was afraid of losing my sculptural language, but I found that it translated very well,” Pénicaud says. “It’s like music — concrete notes on a steel grid.”

Pettersen & Hein

Lea Hein and Magnus Pettersen, of Etage Projects, add color, mirrors and perforated surfaces to their concrete creations to balance the medium’s inherent harsh qualities. Photo by Andreas Omvik

When asked about their design philosophy, Magnus Pettersen and Lea Hein like to quote the artist Richard Artschwager: “If you sit on it, it is a chair. If you look at it and walk around it, it is a sculpture.” Their pieces — a mirror on a tall base of irregular, multicolored concrete blocks, a side table of concrete rods arranged into a sort of labyrinth, available at Copenhagen’s Etage Projects — blur the boundaries between furniture and sculpture. The pair also take after Artschwager and Donald Judd in their minimalist aesthetic and industrial materials (in addition to concrete, they favor steel and iron).

Graduates of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and Sweden’s HDK School of Design and Crafts, respectively, Pettersen and Hein began working together in 2014, and dyeing concrete has always been a critical part of their process. “Concrete has power, because of its heaviness. But when you add color, it becomes organic and poetic,” Hein says. For an exhibition this past spring at Patrick Parrish in New York, pink concrete cylinders and yellow concrete blocks served as supports for an ultra-shiny stainless-steel bench — an impeccable combination of rawness and polish. Hein observes: “We like when brutality and beauty go hand in hand.”