April 9, 2023If Colin King had a free day — which wouldn’t be likely anytime soon — he might come to your house and, well, improve it. First, he would root around in your drawers looking for old things, things you thought were ugly, things he might put on a table upside down or sideways: a pepper mill, a vase, a piece of wood that could serve as a pedestal.

Then, he might scan your backyard looking for exemplary rocks, or twigs, or leaves and add them to his stash. Next, he’d remove some things from your shelves and tabletops and add some of the things he’s found — not too neatly but with an élan that makes your house look ready for the cover of a magazine (he’s styled 50 stories for Architectural Digest) or a coffee-table book.

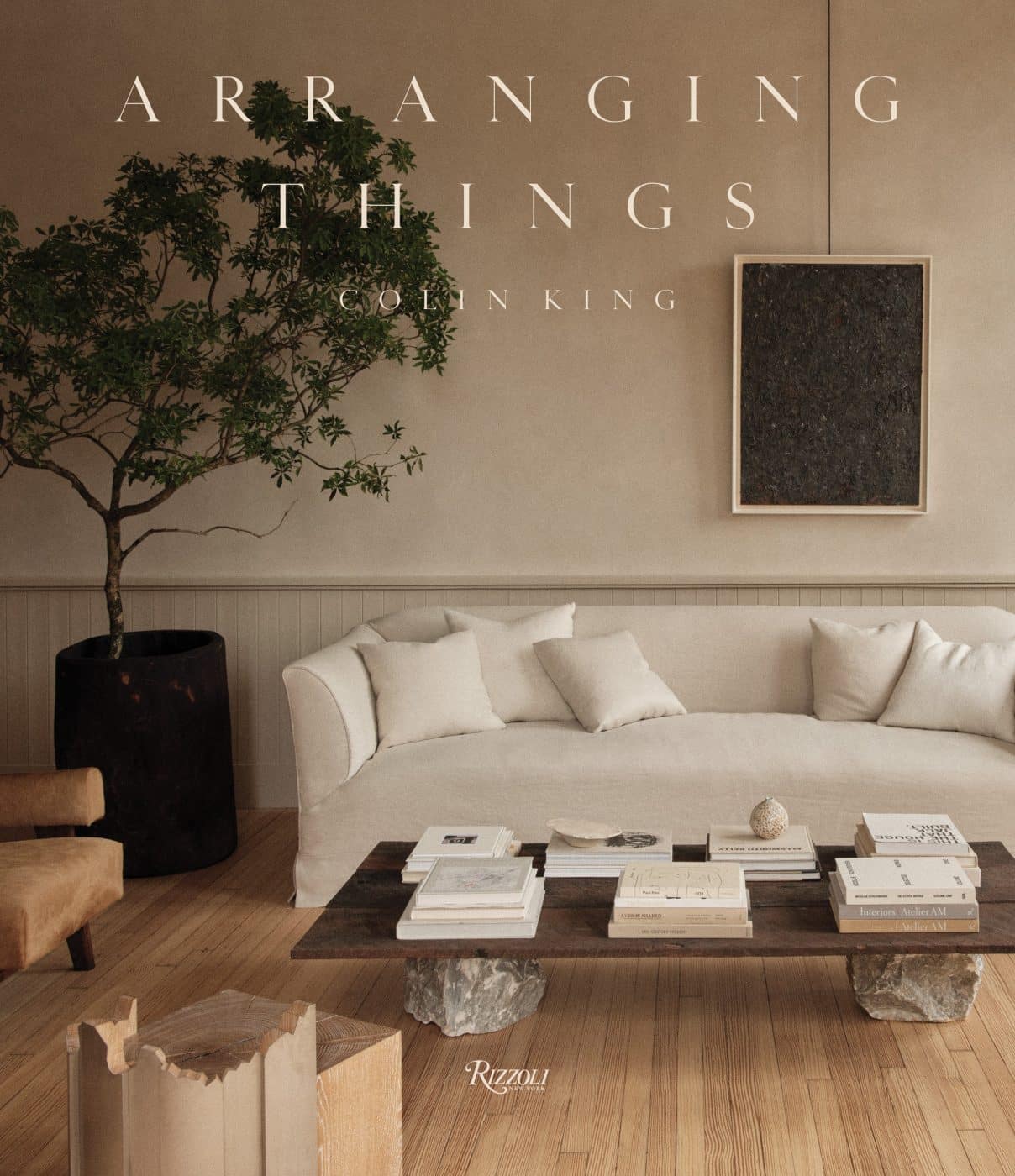

His own first book, Arranging Things, has just been published by Rizzoli, and it’s full of shots he’s styled, mixing objects of intrinsic value with objects that are valuable as contributors to his compelling vignettes. “A stone can become a monolithic sculpture,” he and his coauthor, Samuel Cochran, write. “A branch can fill a vertical void like a line drawing in space. It’s all about giving reverence to ordinary objects and seeing things differently through the power of context and composition.”

The reason King won’t have a free day is that he’s already been discovered by some of the world’s top designers. Robin Standefer, half of the partnership known as Roman and Williams, hired him to style the Roman and Williams Guild — the studio’s chic Soho emporium — for some of its first marketing photos. Since then, she has given King many other assignments. “If you do what we do,” Standefer writes in the book’s introduction, “you need partners whose eyes you can trust. In that way, Colin has offered me a respite. By which I mean: I trust and admire him so completely that I have allowed myself to (sometimes) let go.”

When Standefer couldn’t travel to her client Gwyneth Paltrow’s house for an Architectural Digest cover shoot, guess whom she sent? “As a designer, you often get only one chance to document a room. That photo has to count,” she writes. “Colin captures a room as it ought to be remembered.”

Similar encomiums have poured in from designers like Giancarlo Valle and Monique Gibson, as well as a slew of top photographers. When King isn’t working for them, he’s been working on several product lines, including his latest collection of Moroccan-made rugs for Beni, their patterns inspired by vintage Japanese textiles. His collection for Menu Denmark consists of the kinds of things he often uses when styling rooms: a brass paperweight, an acacia-wood platter, a sculptural lava-stone bookend. Naturally, he styles the photos used to advertise his products, just as he has styled the photos used to advertise pieces from Crate & Barrel and Anthropologie and other corporate clients.

Another growth area for King is designing installations. Starting Memorial Day weekend, the nomadic gallery Objects & Thing will exhibit works by contemporary artists at the LongHouse Reserve, the fabled Long Island home of Jack Lenor Larsen, with King adding objects from Larsen’s private collection to the mix. And in June, during 3daysofdesign, Copenhagen’s annual design festival, he will create an installation at the Audo, a hybrid hotel and gallery space, to showcase his Menu Denmark products. The installations allow him to work in three dimensions, which “is very cool,” he says, “because a lot of my work is about translating three dimensions down to two.”

At 34, King is doing what he most loves doing. In the early, scary days of the pandemic, he started creating small arrangements of things he found around his house and posting them on Instagram. “The routine helped keep me sane,” he says of what became a daily practice. Soon, he had more than a quarter of a million followers, and his hashtag #stayhomestillife became an invitation for people around the world to share their visions. “It is so gratifying to see other people posting, and to see the creativity that was cultivated during an uncertain time” he says.

King never expected to make a career out of arranging things. Growing up on his family’s farm in Baltimore, Ohio (population 2,900), he collected rocks, which he organized by size or shape or color on his windowsill. After college, moving between New York and Los Angeles, he worked as a dancer, a personal trainer, a social media manager and a realtor. He says his friends, who saw him “creating vignettes at home, taking and composing images and always rearranging my surroundings,” told him he ought to be a stylist. “But I didn’t know how to make that a career.” So he started tagging along with photographers like Reid Rolls and Adrian Gaut, first for free and later as a paid stylist.

In 2019, he landed an agent and began taking a variety of jobs — “some as simple as bringing in branches and flowers,” he writes in the book, “and some as complicated as propping an entire house, with a week of full-blown shopping.” In 2021, he moved to a Tribeca loft, a wreck with high ceilings and big windows and plenty of room for collecting. But he was careful not to overdo it. After having Kamp Studios give the walls a mottled, beigey finish that “envelops you in warmth,” he hung only a few small artworks. “Pieces need room to breathe,” he explains. There are a few furnishings with dramatic profiles, including 1950s Finnish dining chairs by Olavi Hänninen, acquired in the U.S. and Scandinavia.

But the building’s stairs and elevators are so small that the sofa, daybed and dining table had to be built in the apartment, per King’s designs. He accessorized with items from 1stDibs, including a 19th-century Flemish mirror from De Nille Antiques; circa 1968 modular tables by Mario Bellini for B&B Italia, from Massimo Caiafa; a pair of 1950s French campaign-style tripod stools, from Bloomberry; a Hans Wegner Heart chair, from Balder Design; and a 1960s desk lamp from Exante Antiques.

King doesn’t have a list of rules for arranging things, a process that is more intuitive than scientific. But a few principles come up during a discussion of his work:

Don’t make it too pretty. “My biggest fear about my apartment was that I was making it too nice. I don’t like rooms that have obviously been decorated.”

No arrangement is permanent. “You can move things around every day. And if you have too many things, rotate some of them in and out.”

There’s beauty in emptiness. “Not every corner or surface needs something. I edit, edit, edit and edit some more. Collecting isn’t about amassing the most stuff. It’s about refining. I’ve never regretted not filling a space.”

Rooms ought to have signs of life. “I use open books, an ajar door, artworks leaning against walls and even half-empty glasses of water. My favorite rooms are the ones where it feels like someone was just there.”

Listen to the pieces you collect. “Some objects want companions — and they tell you so. Other objects want to be alone. I’m very drawn to singular objects that have a lot of power. Not every candlestick needs a mate.”

Natural light can be an object in the room. “Look at where sunlight hits your walls. Often, it forms a rectangle or a parallelogram with lines slicing through it — the shadows of window mullions. That composition can be as interesting as a painting hanging on the wall.”

Ultimately, according to King, arranging things is more about you than about the things. Styling, he says, “can be a daily practice, one that empowers you to see the world differently and find new meaning in it.”