February 28, 2021Photographs by Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton (1904–80) carry with them a heady whiff of past glamour.

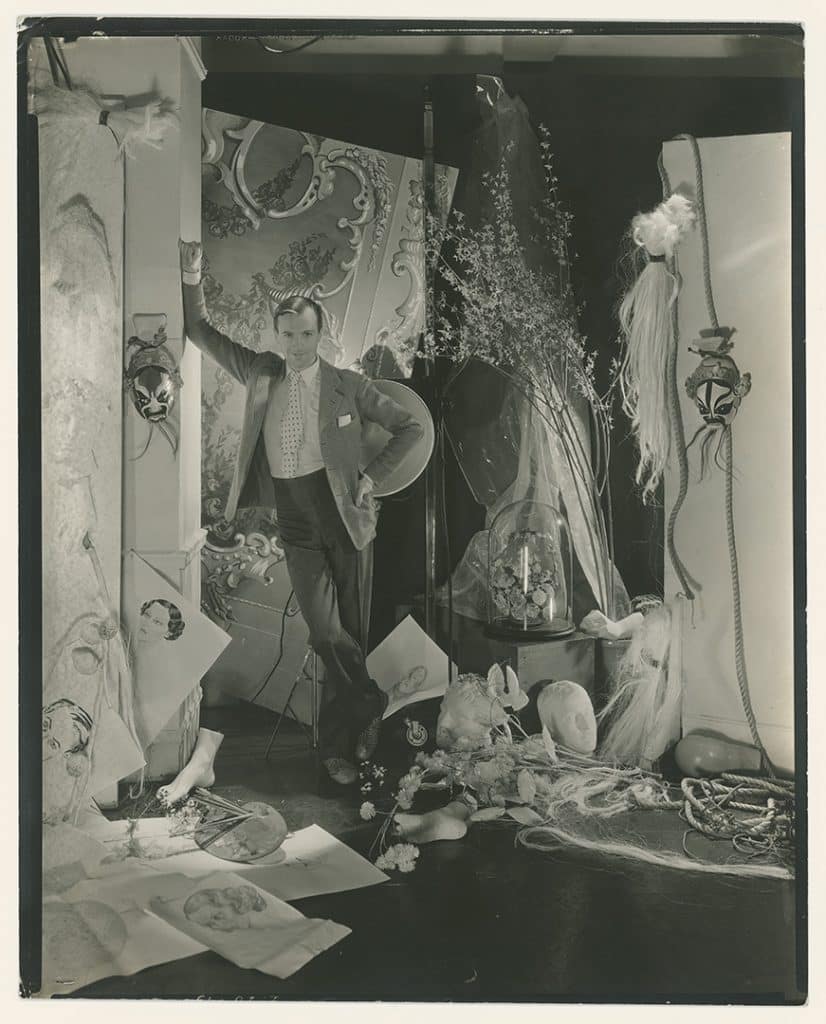

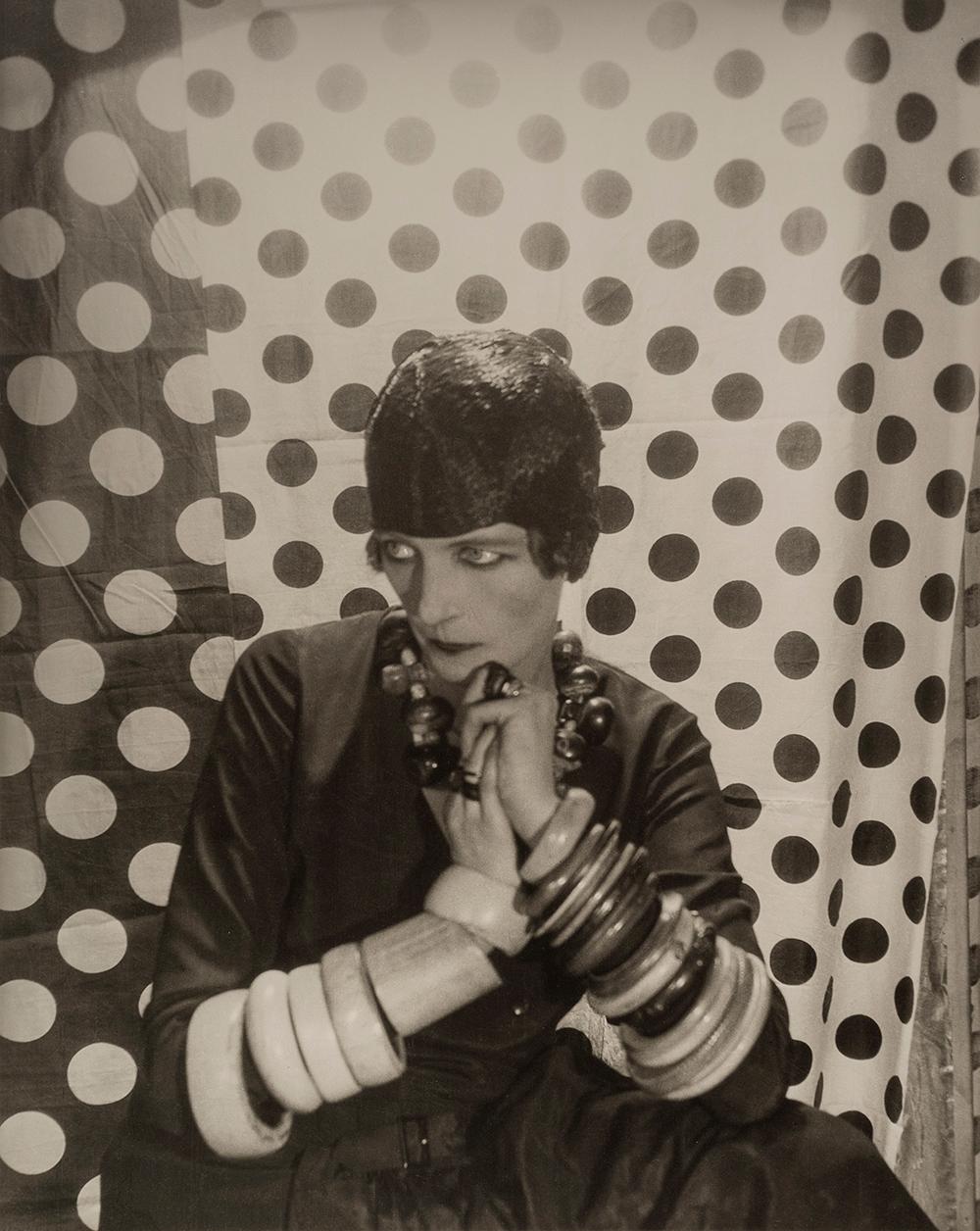

The sepia-toned images he took in the 1920s and ’30s, when he was just learning to use the medium, memorably depicted the Bright Young Things of New York and his native London, showing Bohemian socialites, aristocrats and actresses gathered in country houses, sometimes in costumes, whiling away the hours.

It looks like fun, especially from a pandemic-lockdown viewpoint.

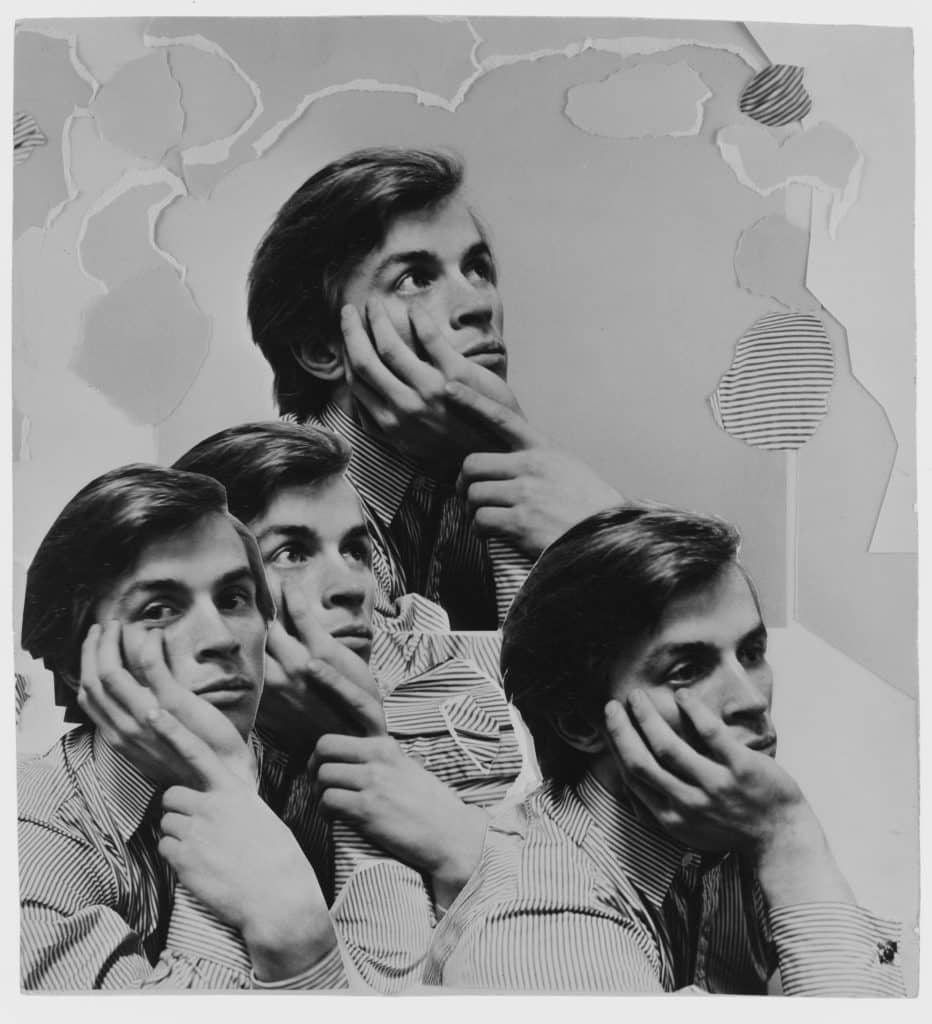

Later, as a Condé Nast photographer and acclaimed tastemaker, Beaton shot pretty much everyone of note in the worlds of art, style and culture, from Salvador Dalí to Barbra Streisand and Francis Bacon. His striking 1955 image of Maria Callas with her hands cupping her face is one of his many photographs that have stood the test of time, each recognized as the iconic image of an iconic person.

Now, a show at St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum — on view through March 14 — gives a slightly Slavic spin to the master’s work. Comprising around 100 images, “Cecil Beaton: Celebrating Celebrity” is the first major survey of Beaton’s work in Russia.

It doesn’t take a stretch to see Beaton’s relevance in this age of following and worshipping the famous (one can easily imagine his Instagram account). In many ways, this exhibition feels right on schedule.

Certainly, the show’s redundant title is apt for Beaton, for whom too much was never enough. Although he hobnobbed with the crème de la crème, he was born to a middle-class family in London and hence, as his friend and sometime subject Truman Capote put it, was a “total self-creation.”

Beaton was interested in surfaces and artifice above all. “Anyone examining his work should remember that his first love was the theatre,” the writer and historian Hugo Vickers points out in his catalogue essay for the show, “and therefore a strong theme of theatricality permeates everything he did.”

And in Russia, his stagecraft finds a fresh audience. Daria Panaiotti, the Hermitage curator who organized “Celebrating Celebrity,” notes that “Beaton is famous in America and Britain but not here, since there has never been a big show of his work.”

The exhibition on view now was in a sense born out of an earlier one, devoted to the work of photographer Annie Leibowitz. “Annie donated some of her portraits, including one of Queen Elizabeth II, which was inspired by one of Beaton’s,” Panaiotti says. (Indeed, the Queen was Beaton’s stated favorite subject, and the current show features a 1945 portrait of then-Princess Elizabeth and her sister, Princess Margaret.)

That got Panaiotti thinking about the parallels between the photographers. And it’s clear that Beaton’s younger peers and everyone who came after him as chroniclers of the famous — Leibowitz, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, et al. — owe him a debt.

Naturally, Panaiotti says, the large number of Russian émigrés in the glamorous circles Beaton photographed was something for the show to emphasize. So, we see images of notable Russians ranging from a 1935 Vogue shot of dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine to a portrait of a young Rudolf Nureyev from the 1960s.

Beaton actually traveled to the USSR in the 1930s, accompanied by no less a personage than Elsa Schiaperelli, at the time Europe’s top fashion designer (a stop in the country was de rigueur for the era’s jet set). But he didn’t take many photos, for a variety of reasons, Panaiotti says, including that it was freezing cold.

Beaton was a prolific painter, sketch artist, costume designer and interior decorator, and these occupations were hardly sidelines. He won three Oscars for costume and production design, including for My Fair Lady, whose Ascot race scene, an eye-popping arrangement in black, white and gray, is among the most memorably tricked-out movie moments of all time.

But photography is his preeminent legacy. London gallerist Giles Huxley-Parlour, a prime source for Beaton’s pictures, notes that there is steady interest in the work. “It’s the style, ultimately,” he explains. “The compositions and the glamour call people back to Beaton.”

“In fact, his pictures were downright “lo-fi,” says Huxley-Parlour, who attributes much of their fun to the fact that the richest woman in the world, for instance, might be posed in front of a handmade papier-mâché background. “There’s something effortless about them,” he notes.

Timothy White — one of the partners in New York’s Morrison Hotel Gallery, which sometime deals in Beaton images — seconds that sentiment: “He was able to create something out of nothing. He could do a lot with strips of tinsel and a bouquet of flowers. He MacGyver-ed it,” says White, a noted photographer himself, who admires how Beaton “pushed the boundaries of the medium.”

If you’re in the market to buy one of his works, the traditional rules for collecting photographs apply, although Beaton has broader appeal than some other photographers because of the added luster of his contributions to fashion and costume. The most valuable pictures involve famous sitters, including the Bright Young Things — socialite Elizabeth Ponsonby, collector Harold Acton and authors Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford (along with some of her five sisters) among them — whose celebrity was partly Beaton’s creation.

As for most photographers, Beaton’s earliest pictures are particularly sought-after. They are also rare, since, as Huxley-Parlour notes, “the vast majority of his career happened before there was a photo market.” These prints tend to be smallish and sometimes show a bit of wear, but they still bring top prices.

In the 1970s, photography gained traction as a collecting field, and Beaton began working with dealers to make multiple prints of certain images. “If you want a big flashy one for your wall, you might prefer a later one,” Huxley-Parlour says.

Prints generally sell for between $1,000 and $5,000, says Thomas Cary, of The Cary Collection, in Connecticut, which has hundreds of Beaton items on offer, including scrapbooks, photographs and artworks. He adds that the art pieces, “like the wonderful drawings or designs for stage sets, can go for a lot more,” explaining that one of the attractions of these pieces for connoisseurs is that Beaton’s “use of color was amazing.”

Beaton favored women as subjects, as 1stDibs current inventory indicates. In 1930 alone, actresses Gertrude Lawrence, Anna May Wong, Norma Shearer, Corrine Griffith and Tallulah Bankhead; and writers Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer and Dame Edith Sitwell all sat for memorable portraits. Johnny Weissmuller, star of the Tarzan films of the 1930s and ’40s, provides a rare bit of beefcake in a 1932 image.

Despite her exhibition’s focus on the famous, Panaiotti’s favorite picture is of an anonymous woman: A WAAF cadet in training lines up on parade, RAF Bridgnorth, Shropshire, from 1941.

“It’s a beautiful image,” Panaiotti says of the cadet captured in profile, noting that Beaton’s war photography is an underappreciated, and rich, segment of his work. “We don’t know her name, but she’s a wife, a daughter, and she is becoming an emancipated lady for her country.”

The subject is a far cry from the Bright Young Things, but the picture sounds a nice patriotic note from a photographer who knew a good look when he saw one.