April 20, 2025Cartier’s signature red box has become a global symbol of luxury. The jewelry house’s cross-cultural appeal can be traced back to the vision of three brothers: Louis, Pierre and Jacques — grandsons of founder Louis-François Cartier, who established the Parisian firm in 1847. At the turn of the century, the trio transformed the family business into a worldwide powerhouse with an entrepreneurial “divide and conquer” approach to commerce that was far ahead of its time. Louis remained in Paris, Pierre opened a New York flagship, and Jacques established a London boutique. Each brought his distinct creativity and market sensibility to the brand, producing pieces that merged French elegance with his location’s individual taste.

More than 350 of the brand’s treasures are on display now through November 16 at London’s V&A Museum in “Cartier” — the UK’s first exhibition in more than 25 years dedicated to the legendary house. It traces Cartier’s evolution from the early 1900s to today, with a particular focus on the craftsmanship of its British workshop.

Given London’s royal heritage, the show fittingly highlights the jeweler’s relationship with the monarchy, which began with King Edward VII, Queen Victoria’s son and one of the house’s earliest patrons. This association blossomed into numerous commissions for royals across Europe and Russia, which are represented by a stunning array of diamond-studded tiaras and diadems demonstrating Cartier’s mastery in balancing opulence with delicate details.

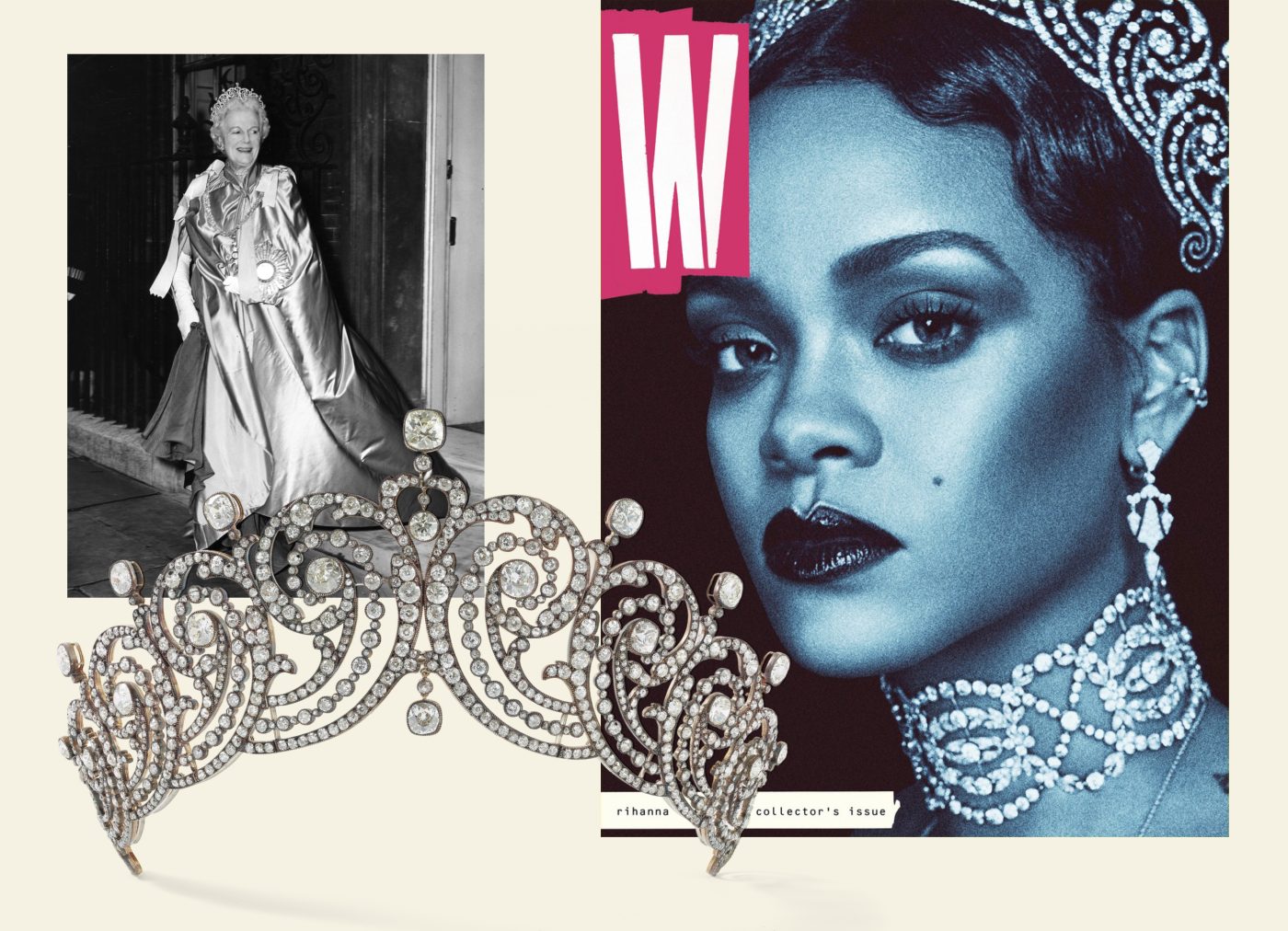

The Scroll tiara, which was commissioned in 1902 by the Countess of Essex, has been worn by Queen Elizabeth and Rihanna, who donned it on the cover of W Magazine in 2016. Photo of Queen Elizabeth by Getty Images, Scroll tiara image by Nils Herrmann, Collection

Cartier © Cartier

“One of my absolute favorite discoveries during the curatorial research process was an opal, diamond and platinum tiara made by Cartier London in 1937,” says cocurator Rachel Garrahan. “Never exhibited before, it was commissioned by the Marchioness of Hartington, later Duchess of Devonshire, using opals her husband had given her after a trip to Australia in 1936. Not only are the stones exceptional, but it’s rare to find a Cartier piece from this era using opals. In fact, 1937 was a momentous year for Cartier London, as it made more tiaras that year than any Cartier branch before or since.”

Other headpiece highlights include the elaborate garland-style Scroll tiara, commissioned in 1902 for the Countess of Essex, which was worn by Rihanna on the cover of W Magazine in 2016, and the delicate floral-themed Halo tiara, famously worn by Kate Middleton when she married Prince William.

The first gallery explores Cartier’s eclectic influences, including Persian, Indian, Chinese and Egyptian art, and practice of integrating apprêts — repurposed antique jewelry or fragments — into new works. This blending of cultural motifs gave the house’s designs an irresistible mix of nostalgia and modernity, imbuing jewelry with joy, exuberance and magic. The room brims with global wonders, including vanity cases inspired by 1920s Egyptomania, diamond brooches shaped like Japanese obi knots and cigarette cases covered in “Russian ray” guilloche enamel.

Jacques Cartier’s 1911 trip to Delhi deepened the house’s ties to India, a country long associated with the finest gemstones — especially diamonds from the Golconda region. He connected with maharajas and gem dealers, resulting in a surge of vibrant jewels featuring carved emeralds, rubies, sapphires and diamonds in botanical motifs — a design dubbed Tutti Frutti in the 1970s. The show contains two rare examples of this avant-garde jumbled-gemstone style: a double clip brooch and a chunky bracelet from the 1930s, both once owned by socialite Linda Lee Thomas, wife of composer Cole Porter — perhaps a playful wink at his famous song “Anything Goes.”

Naturally, the exhibition acknowledges Cartier’s glittering clientele. One jaw-dropping piece on display is Mexican film star María Felix’s 1968 snake necklace — a life-size serpent crafted in gold and encrusted with diamonds, with scales enameled in the colors of the Mexican flag. The body is articulated, for a fluid, lifelike quality that delighted the flamboyant actress, who adored reptiles. She reportedly had a pet crocodile that she asked Cartier to immortalize in another audacious necklace, this one composed of two interlocking crocs, one covered in brilliant-cut fancy intense yellow diamonds and the other set entirely with emeralds.

The celebrity-associated showstoppers don’t stop there. Other mega-watt pieces with VIP provenance include a 170-carat diamond and Burmese-ruby collar necklace — commissioned by the maharaja of Nawanagar in 1937 — that socialite Gloria Guinness wore to Truman Capote’s 1966 Black and White Ball in New York. Then, there’s the dazzling necklace gifted to Elizabeth Taylor by her third husband, the director Mike Todd, featuring huge hard-candy-size Burmese rubies nestled into a latticework of diamonds, a piece the actress once described as “like the sun — lit up and made of red fire.”

Garrahan explains that many of these rare vintage pieces throw light on a wider historical narrative, providing fascinating insights into the lives and experiences of the people who wore and created them. “The maharaja of Nawanagar’s Tiger’s Eye turban ornament is the perfect marriage of Indian jewelry tradition and Art Deco,” she says. “Until now, it was thought to have been a commission by the maharaja, but new research has uncovered that it was in fact a stock piece, which he bought while he was in London for the coronation. These creations strongly evoke a moment in royal and London history of jeweled splendor that, in large part due to the Second World War, was never to be seen again.”

Cartier’s creativity is boundless, but the house is also cherished for its iconic designs and motifs that have maintained relevance and wearability through the decades. Chief among these is the panther, championed by Jeanne Toussaint, Cartier’s creative director from 1933 until the 1970s, whose many big-cat-themed creations transformed the form into a symbol of feminine sensuality and sophistication. In truth, the sleek feline had been part of the brand’s iconography since 1914, when it inspired a diamond and black-onyx watch, an example of which is included in the exhibition. It’s still one of the brand’s best-selling motifs — especially in the form of the Panthère de Cartier wristwatch, worn by such modern muses as Bella Hadid, Zendaya and Dua Lipa.

Two other iconic Cartier creations are the Love Bracelet (1969) and Juste Un Clou (1971) collection, both originated by Aldo Cipullo at Cartier New York. These sleek, modern designs reflect Cartier’s shift toward clean lines and avant-garde experimentation, a move that was, in part, fueled by the youthful energy and artistic innovation of Swinging London. Indeed, although the miniskirt may have come first, Cartier’s New Bond Street boutique had its own emblem of fun-loving hedonism in the 1967 Crash wristwatch. Conceived by Jean-Jacques Cartier, son of Jacques, who helmed the branch at the time, and designer Rupert Emmerson, the watch is famous for its surreal distorted dial, marking a rebellious moment in classic horlogerie.

According to urban legend, the abstract timepiece was inspired by a Cartier Baignoire that had been involved in a car accident. Salvador Dalí’s paintings of molten clocks are also thought to have influenced the dial’s fluid shape. Neither tale has ever been categorically confirmed or denied by Cartier HQ, adding to the model’s enigmatic aura. Interestingly, the Crash divided opinion at the time, and it saw very limited sales in the early 1970s, making the pristine original on display at the V&A one of its rarest exhibits. Today, the Crash has made a significant U-turn in popular culture, having become one of the house’s most sought-after watches, its modern vintage and rare heritage editions worn by an A-list that counts among its members Tyler, the Creator; Kim Kardashian; Timothée Chalamet; Jay-Z; and LeBron James.

For Garrahan, who coauthored the exhibition book with fellow curator Helen Molesworth, Cartier jewels conjure a magical sense of depth, perspective and symmetry, as well as cherished memories and emotions.

“There is a brooch that Jacques Cartier commissioned for his wife, Nelly,” says Garrahan. “Her birthstone was amethyst, the four diamonds represent their four children, and these are edged in sapphires to represent the protection of Jacques, whose birthstone it was.” The brooch became one of Nelly’s favorites, she notes, adding, “I love jewelry with human stories, and this one is particularly special given the importance of the Cartier brothers. Their close bond was one of the secrets to the company’s success. They established a legacy which would live well beyond their years.”