October 2, 2022Carleton Bates Varney Jr., who was a pal of mine for 30 years and died in July at age 85, was larger than life, congenitally upbeat and positive. “I’m a happy person,” the noted interior designer told the Palm Beach Post in 1998, “and I want the world to be a friendly, colorful place.”

A large man, tall and broad chested, with sparkling blue eyes and a bright smile, Varney wore colorful outfits accented with red socks and his signature cravat, a vibrant Hermès silk square cut in half that he wrapped around his neck like a tie but that cascaded down his front like a giant foulard.

He earned the nickname “Mr. Color” not because of his wardrobe but thanks to his liberal use of Kelly green, azalea pink, cantaloupe orange, fire-engine red and royal blue in his design schemes. His oversize floral patterns were popular from Hollywood to Palm Beach — even after the New York and Los Angeles design worlds turned to minimalism in the 1990s, along with “must” shades of white, gray and beige.

His work for President Jimmy and First Lady Rosalynn Carter was perhaps his most salient introduction to the American public. During the Carter Administration, he styled White House state luncheons and dinners and served as the color consultant for the Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta. He also designed President and Mrs. Carter’s log-cabin home in Ellijay, Georgia, and worked in various capacities for Nancy Reagan, Laura Bush, Dan and Marilyn Quayle (for whom he designed the official vice president’s residence at Number One Observatory Circle).

But Varney’s greatest influence on the decorating world during his 60-year career was as president and owner of the Manhattan-based Dorothy Draper & Co., among the oldest interior design firms in America. It was named for its founder, Varney’s dashing mentor, who is credited with being one of the founders of the interior design industry in America. She was a society-lady-turned-decorator, imperious, ever-confident and captivating. She is best known for her commercial projects, some of which still exist today, like the Greenbrier, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia; and the Hampshire House on New York City’s Central Park South. Her projects are memorable for their overscale prints and splashy palettes of vivid colors borrowed from a summer garden.

“Varney was the last link to that group of pioneering women designers in the nineteen twenties who established the profession,” says Donald J. Albrecht, a nationally recognized design historian and curator.

Varney adopted Draper’s style, palette and verve. Americans particularly embraced his reimagining of the 400-room Grand Hotel, a national historic landmark built on Mackinac Island, Michigan, in 1887. Varney lined the floors with wall-to-wall carpets depicting giant red geranium blossoms with green leaves on a black background and upholstered the dining chairs in wide green and white stripes, a color scheme he also applied to a barrel ceiling in another setting. Each and every one of the 397 guest rooms was individually decorated in a different scheme.

Other hotels that illustrated his design talent include the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan; the Breakers, Brazilian Court and Colony in Palm Beach; and the Westbury properties in London. His major ongoing work on Draper’s original 1946 design for the Greenbrier was perhaps his favorite project. He had an office in the hotel until the end, receiving “groupies, young and old, who would come up and greet him as a dear friend whenever he was there,” says Robert Rufino, the style director of House Beautiful.

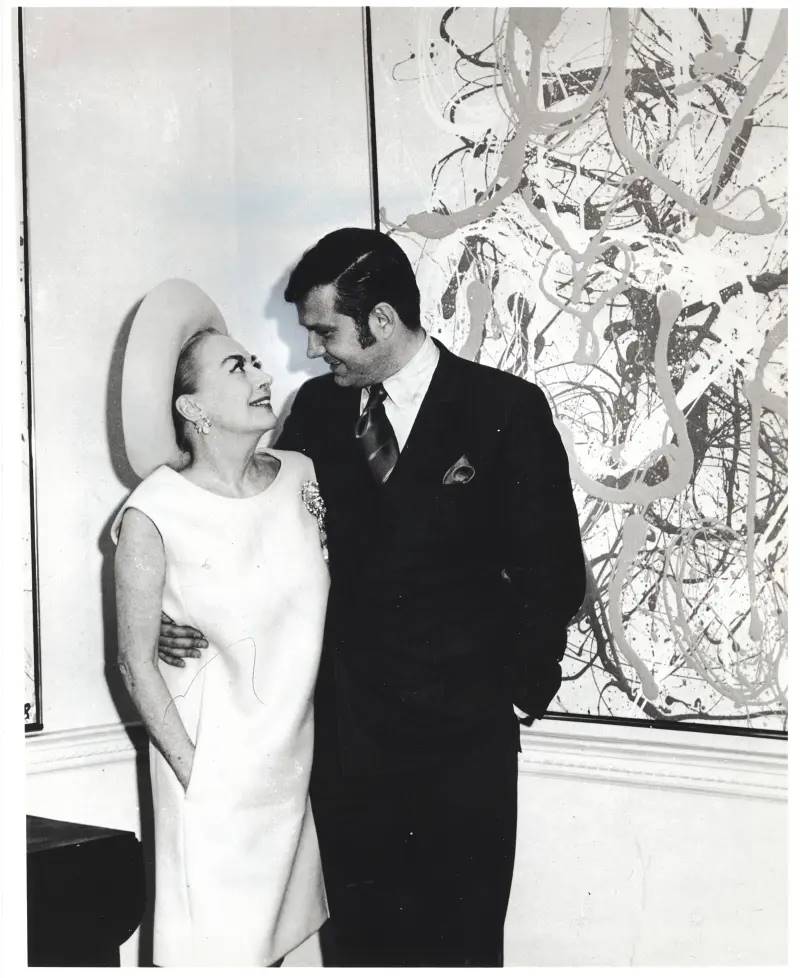

Among his many famous private clients were Joan Crawford, Fay Wray, Judy Garland, Ethel Merman and the shah of Iran.

Varney was much more than a decorator, however. He wrote 37 books (including the colorfully titled novel Kiss the Hibiscus Goodnight). His “Your Family Decorator” column was syndicated in hundreds of newspapers decades before Martha Stewart became a household name. (“He had a voice,” says Rufino.) Over the years, he was a design editor at Good Housekeeping magazine, a textile and wallpaper entrepreneur (founding Carleton V Ltd. in 1973 with his late ex-wife, Suzanne Lickdyke Varney) and the designer of clothing lines. He even hosted a daily TV talk show, “Inside Design,” in 1966.

He always thought big. He opened his firm’s archives to the Museum of the City of New York when it mounted the 2006 exhibition “The High Style of Dorothy Draper.” Although not involved in the show itself, he organized the opening night black-tie party.

“The night was an extravaganza,” recalls Albrecht, who curated the show. “He hired Peter Duchin to play the piano. He flooded the facade of the museum with pink spotlights. He installed white rattan chairs upholstered in Draper’s signature cabbage-rose pattern for the guests.”

From a young age, Varney was ambitious and hardworking. Growing up in Lynn, Massachusetts, he took tap and ballroom dancing lessons, played basketball and participated in flower-arranging contests. After graduating from Oberlin College in 1958, he earned a master’s degree in education from New York University and taught at New York–area private schools. He had dreamed of being a set decorator — which makes perfect sense in retrospect — but could not find a job. Through his friendship with Leon Hegwood, who then owned Dorothy Draper & Co., he was hired at the firm in his 20s as a draftsman. “I did everything — vacuuming the floor and emptying the wastebasket,” he told the Houston Chronicle in 2018. “In fact, I still do all of that.”

From the start, he embraced the Draper ethos, as is evident in the entertaining, affectionate and comprehensive biography of the designer he wrote, The Draper Touch: The High Life and High Style of Dorothy Draper, first published in 1988 and reissued this year by Shannongrove Press. In it, he calls Draper “the Grand Duchess of Decorating.” She was very tall, handsome, beautifully dressed, imperious and unconventional. She single-handedly invented the modern baroque style, with oversize white plaster appliqués, oversize mantels and other brilliant plaster confections that looked like whipped cream, often placed against black-lacquered walls.

After Draper died, in 1969, Varney bought the firm and ran it until his death. (One of his three sons, Sebastian, has now taken it over.) He maintained the firm’s grand neo-baroque style, bodacious fabrics and flair for publicity. His influence can clearly be seen today in the color-saturated interiors of designers from Miles Redd and Katie Ridder to Anthony Baratta and Kelly Wearstler.

But it’s his warmth and larger-than-life personality for which he will likely be best remembered by those who knew him. He lit up every room he entered. He liked people, and people liked him. He was a great storyteller, full of Irish blarney (although not of Irish descent, he cultivated an Irish persona, had a beloved home in Ireland and decorated Dromoland Castle, Ashford Castle, Adare Manor and the residence of the American ambassador to Ireland, among other projects there).

“Whenever I served on a design industry panel with him, it was always an event — he could talk the pants off anyone,” Rufino recalls. “He was one of a kind. There will never be anyone like him.”