May 30, 2016Steve and Brooke Giannetti, an architect and an interior designer, respectively, at their Ojai, California, home, which is documented in the new book Patina Farm. Top: The kitchen exemplifies the couple’s commitment to fostering a feeling of casual elegance. Photos by Lisa Romerein from Patina Farm by Brooke Giannetti and Steve Giannetti, reprinted by permission of Gibbs Smith

Thelma, Louise and Dot are restless. It’s 4 p.m. at Patina Farm, in California’s bucolic Ojai Valley — dinnertime for the three pygmy goats. The diminutive creatures, currently nudging their way onto a shaded stone porch, have certainly hit the farm jackpot: The French doors of their adoptive home, shaded by craggy ancient oaks, open to an expanse of golden gravel dotted with snack-worthy vegetation.

Meanwhile, rustic fountains, simple furnishings and eclectic outbuildings suit the needs and acute aesthetics of its human residents. A mix of perfectly weathered materials ensures that you can’t quite put your finger on how long the structures have been there or exactly what style they are. And that’s precisely the intention of the owners, whose thoughtful choices are now the subject of a book, Patina Farm (published by Gibbs Smith).

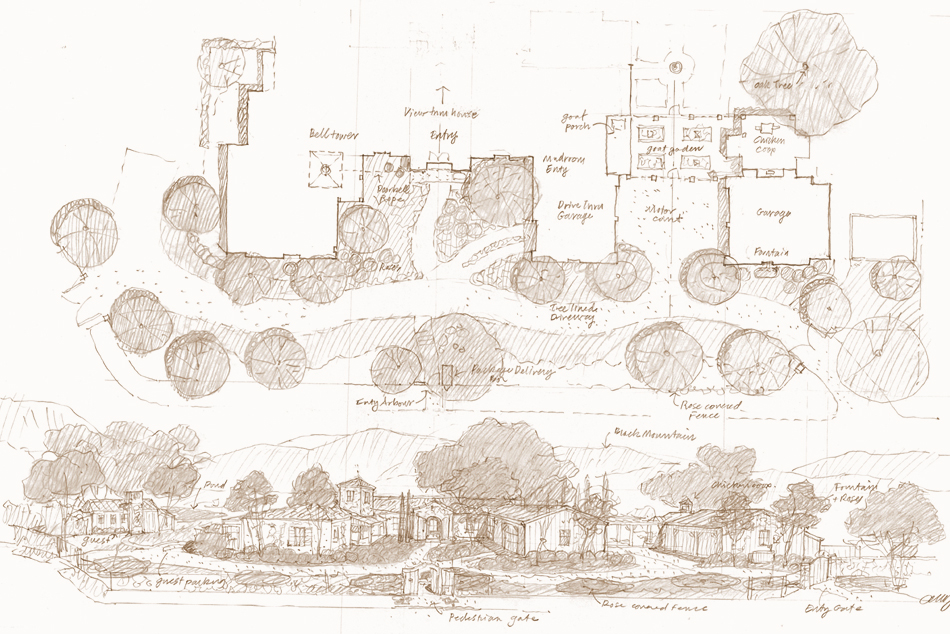

The residence of husband-and-wife team Steve and Brooke Giannetti — he’s an architect, she’s a decorator who also runs the acclaimed Velvet & Linen blog — is just shy of three years old. With an empty nest on the horizon (sons Charlie and Nick are 22 and 19 respectively; daughter Leila is 15)) and limited space for gardening on their previous Santa Monica property, the Giannettis sought out this five-acre expanse to build a bell-towered house, barns, coop and guest bungalow overlooking the fields, lake and gardens. Steve’s architectural drawings detail how the family created a new daily rhythm with horses, miniature donkeys, a flock of chickens, four dogs, a bunny and the aforementioned goats. (The Giannettis’ learning curve has been as steep as the terracing, with Thelma, Louise and Dot munching through the romantic landscaping of roses, cypress and espaliered apples, not to mention their share of antique chairs, before the couple reconfigured the fencing and bequeathed them the original kitchen garden for sleeping.) Below, the greenhouse-centered potager is surrounded by fields where the donkeys can play.

In the lush yet livable interiors, Belgian and French market treasures, including several carved-wood doors and sets of antique hardware, mingle with furnishings from the couple’s own line, Giannetti Home, many of whose pieces scale petite: Arms and legs are thinner than in contemporary styles, and backs are built often higher, to fit old-world proportions. Collections are elegantly displayed, from large wood cutting boards balanced on a mantel to plaster architectural fragments — from Steve’s family business, Giannetti’s Studio, whose clients include the United States Capitol and Monticello — dotting the book shelves in his office.

The home’s open floor plan was intended to bring family and guests together. Antique Swedish furnishings and a generous window seat provide ample space for lounging, and three panels of Gracie wallpaper add a touch of formality while managing to conceal the television.

For this couple, patina is how they create a relaxing and beautiful home. “It makes a place feel alive,” explains Steve, “as opposed to something that’s painted white and perfect.” Here, the bare brass in the kitchens and bathrooms are just starting to get good. “Nothing will age un-lacquered brass more than a teenage boy,” Brooke says of her son Nick’s bathroom.

Introspective recently spoke with the couple about what compelled them to write the book, why Jefferson’s ripping apart of Monticello is liberating and how rewarding it is to create a home that’s as lovely as it is livable.

This is an unusually considered and flexible space. It’s easy to envision how you live here.

BG: You have to have some honesty about the way you live. In so many houses, people say, “We’re going to stick a porch outside the bedroom, and we’re going to have coffee out there.” That’s never going to happen, I’m sorry. Even if you put a coffeemaker upstairs, you’re just not going to do it.

SG: We saw in our Santa Monica house how the rooms evolved as the kids got older. So we set out to plot that. You’re designing for eighty percent of the time, and eighty percent of the time it’s the two of us having dinner in front of the fire in the kitchen, at that little table. If more than one person comes over, we’ll go to the big table. We always try to think about experiences more than rooms. You’re not building a thing so much as a place for things to happen.

BG: We didn’t want too much excess square footage in the house. Like the guesthouse — that can work for our son Charlie when he comes to visit, although he always ends up wanting to stay in Nick’s room. It’s really cute.

The couple placed the dining space at the center of their home to encourage its use for more than just formal meals. The placement of large glass doors at either end of the space make guests feel as though they’re eating alfresco.

Antique wooden barn beams frame the glass doors and sit atop the rough-hewn stone fireplace in Steve’s office. A vintage industrial light is clamped on the side of his desk, a repurposed refectory table.

At what point in building Patina Farm did you decide to write this book?

BG: I think we always knew we would.

SG: We wanted to explain our choices. Like, if I only have light on one side of the room, I don’t get light bouncing off the other side. That feels uncomfortable. So every room in the house has light on two sides, mostly three, so it glows.

BG: In the book, I talk about how to lay the house out. But while you’re thinking about layout and lighting, you’re also thinking about how you move through it during the day. East sun is over there, and that’s probably the best place for the bedrooms. Have the whole house facing south — that’s better for the light. By including Steve’s drawings, we could offer technical information in a prettier way. Steve chose a lot of elements based on classical architecture and the 1970s book A Pattern Language.

SG: I’ve read that so many times. It’s the source of all my secrets: the farmhouse kitchen, low sills, terrace slope, a room of one’s own.

How did you imbue a new-build residence with an air of permanence?

SG: We tried to bring some old-house quirkiness into it with all the old materials. John Saladino had done these really thin steel doors in his Montecito villa. I couldn’t find a window guy to do it, because they were too heavy — they all had those big lockboxes. So we found a guy who made super-thin frames.

BG: And this house has a calm palette that’s barely there. The thinness of the window mullions gives it transparency. The stone gives it heft. I wanted the cabinetry to be antique. Even all the bathrooms have antique pieces and sinks, and the medicine cabinets are all old framed mirrors.

What the Giannettis call the master bedroom’s “barely there” palette, which incorporates pale blues and pinks and golds, was inspired by the colors of the sunrise in the east-facing room.

Plaster fragments, painting supplies and a 1940s black-and-white photograph of Giannetti’s Studios, Steve’s family business, occupy shelving created from scaffolding.

And the doors are all different.

SG: All the doors had to be old, . . .

BG: . . . which almost killed Steve. We took a trip to Belgium and found a bunch of them, but they were all different sizes. You needed to change the sizing of all the frames — they’re all steel frames embedded in plaster. And we hung the doors on them.

SG: It’s not like a regular wood frame, on a regular wood door, with regular hardware, in a door schedule. It’s all super-custom. “Oh, I want old doors! How do I close them? How do I make them latch?” Those questions don’t seem so hard until you try to answer them and realize how tricky they are. And now a lot of our clients want those doors.

What’s the secret to creating a home that’s equally casual and dignified?

BG: We have so many animals and enough kids that we can’t live with something that has to be perfect. I don’t want to yell at my kids to take their feet off something or worry where the dogs are going. I’ve always tried to find that place where beauty and livability connect.

SG: The whole house is based on that three-to-five rectangle of classical proportion — the golden rectangle — all the sheets of glass, the rooms.

BG: The goal is for no one to really know when it was designed.

One of the children’s rooms was transformed into a multipurpose reading and lounging space. Painted wood shelves that once held an extensive sneaker collection now house a design library.

Which great houses and designers did you turn to for inspiration?

SG: Timeless, elegant places. Saladino’s design holds up. We looked at a lot of Belgian design when we did this: Raymond Rombouts — who did Axel Vervoordt before Axel did it in the ’60s, which looks as fresh now as it did then. Mount Vernon. Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello has the thinnest window mullions and all these clever secret passages. It’s got a doorbell-type contraption with pulleys: You open one door, and another opens on its own. And Sir John Soane’s Museum, with all the plaster.

BG: Jefferson ripped his house apart several times. If he can rip it apart, so can we. It was very liberating to know that Jefferson said, “That didn’t work. Let’s try something else.”

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore

Brooke & Steve Giannetti’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs