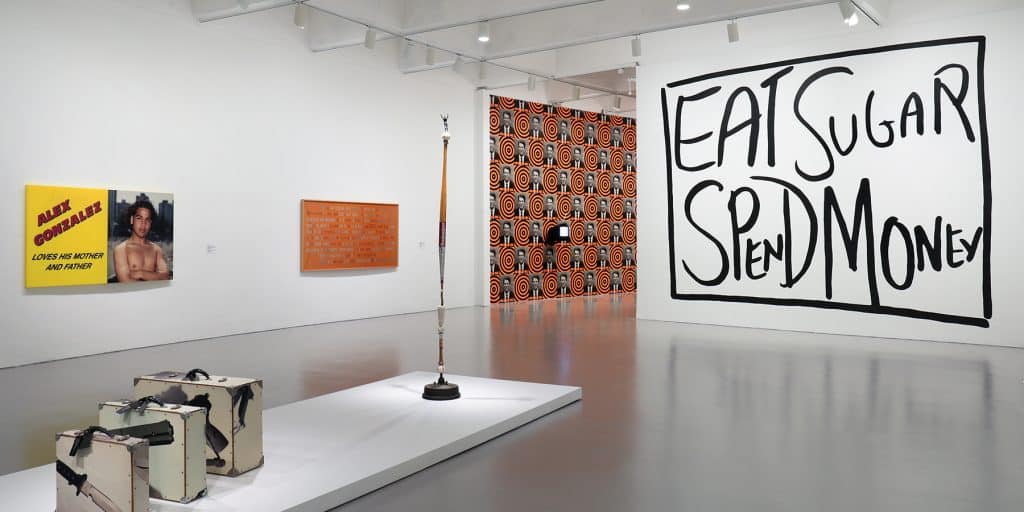

April 1, 2018Barbara Kruger‘s Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987, is among the attractions of “Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s,” at the Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum (photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art.com, Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland, art © Barbara Kruger, courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York). Above: An installation view shows off Jessica Diamond’s text-based T.V. Telepathy (Black and White Version), 1989 (photos by Cathy Carver unless otherwise noted).

I shop, therefore I am.” In updating René Descartes’s cogito for a culture of consumerism, artist Barbara Kruger did more than swap out the key verb. She set her version in a signature sans-serif typeface (Futura bold italic), deployed an agitprop palette (black, white, red) and strategically positioned the message on a placard held in the thumb and middle finger of a disembodied hand (a repurposed photograph). Kruger’s 1987 work, realized in billboard-size vinyl, is the enduringly charming and subversive mascot of “Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s,” on view through May 13 at the Hirshhorn Museum, in Washington, D.C.

“The title ‘Brand New’ can be read ironically, as a reference to an insatiable consumer culture that can’t get enough of the latest products,” says Melissa Chiu, director of the Hirshhorn. “Yet it also intends to convey the genuine, fresh excitement of an era driven by desire and gratification.”

Rather than simply trace the artistic manifestations of a tumultuous decade, the exhibition brings together nearly 150 works that emerged from, reacted to and ricocheted off its milestones: the maturation of the free-spending Me generation, the AIDS crisis, the birth of the personal computer and the flourishing of cable TV (including the 1981 launch of MTV, which went on to spotlight Richard Prince, Robert Longo, Jenny Holzer and the like in its 30-second “Art Breaks”).

The Boutique of the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1980, by the Canadian collective General Idea. Courtesy Esther Schipper, Berlin

Presented in a loose chronology from 1979 to 1989, the exhibition is organized according to several themes. One of these, “Sampling History,” encompasses James Welling’s tile photograms, which act as wall-mounted riffs on Carl Andre, and Jeff Koons’s forever-new rug shampooer, illuminated by Dan Flavin–esque fluorescent tubes. Another, “Hygiene and Contamination,” includes a Robert Gober sink and Tishan Hsu’s 1988 Biocube, clad in flesh-toned porcelain tiles inflamed with pustule-like protrusions. With the additional themes “TV Culture,” “Product Placement” and “Political Activism,” the show addresses collapsing boundaries — between high and low, artist and entrepreneur, gallery and retail store, object and concept, fantasy and reality.

“What is interesting about this material world of the 1980s is that it is material,” says Hirshhorn curator-at-large Gianni Jetzer, who organized the exhibition. “The commodity is not the product, but rather the message and the information around the product become the new commodity and the new structure of value.”

The entrance to the exhibition displays three works. One wall is devoted to Haim Steinbach’s on vend du vent (1988), an all-caps proclamation that translates from the French as “We sell wind.” Nearby, a monitor loops the Ridley Scott–directed Apple commercial that played during the 1984 Super Bowl. Its depiction of a black-and-white Orwellian hellscape disrupted by a plucky hammer thrower in a tank top and red shorts promised that the imminent arrival of the Macintosh would demonstrate “why 1984 won’t be like 1984.” There is not a computer in sight.

Self Portrait, 1986, by Andy Warhol

Completing the introductory trio is a bronze plaque by David Robbins that reads, “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy.” This utopian erasure of the present in favor of the past and the future may smack of Stalin, but in fact, the 1987 work replicates the sign that welcomes visitors to Disneyland. The statement is credited to Walt Disney himself. Jetzer describes it as the motto of the show.

If all of this sounds ambitious — art objects referencing and becoming commodities, commodities and artists elevated to the status of brands, dystopian and utopian impulses coexisting — that is the intention. “For me, it was very important not to simplify the eighties, which were contradictory and complex,” says Jetzer. “The whole show is organized to have multiple voices in the same space.”

If there’s one artist who seems particularly vocal here, however, it’s Andy Warhol. His philosophy that “good business is the best art” permeates “Brand New,” and a fright-wigged 1986 self-portrait — nearly seven feet square — is matched with Not Warhol (1984), Mike Bidlo’s wallpaper riff on Warhol’s screen-print of a New Jersey cow. A slideshow provides photographic documentation of Bidlo’s re-creation of Warhol’s Factory at PS1 in New York.

John, Not Johnny, 1987, John Dogg. Courtesy Venus over Manhattan

“It is the appropriation of the artistic entourage,” Jetzer remarks of the 1984 project, for which Bidlo donned a leather jacket, striped T-shirt and Wayfarers to become Warhol and tapped David Wojnarowicz to play Lou Reed. “It’s quite interesting as an homage to Warhol, who was much admired as one of the masters of self-branding and who embraced consumer society since the 1960s.”

The pieces in a section devoted to “The Artist as Brand” are especially prescient. Among them is Robbins’s Talent (1986), a wall of 18 slick head shots for which he convinced his artist friends (including Koons, Holzer, Sherman and Longo) to pose as aspiring actors. Fascinated by advertising, Ashley Bickerton is represented in this section by a 1988 “self-portrait” that takes the form of a wall-mounted case plastered in logos: Nike, Body Glove, Tylenol, Fruit of the Loom — a mix of brands used by the artist and ones that paid him for placement.

So, what actually was brand-new in the 1980s? “I think eventually what was really brand-new was that from then on you could load all kinds of messages into all kinds of material objects,” says Jetzer, pointing to Alan Belcher’s repurposed and repriced bottles of Solo fabric softener, to which he added colorful labels that included the words LOGO, COLA, AIDS. “That makes everything new, because you can recombine everything,” the curator explains. “There are as many possibilities for recombination as there are ideas on planet Earth.”