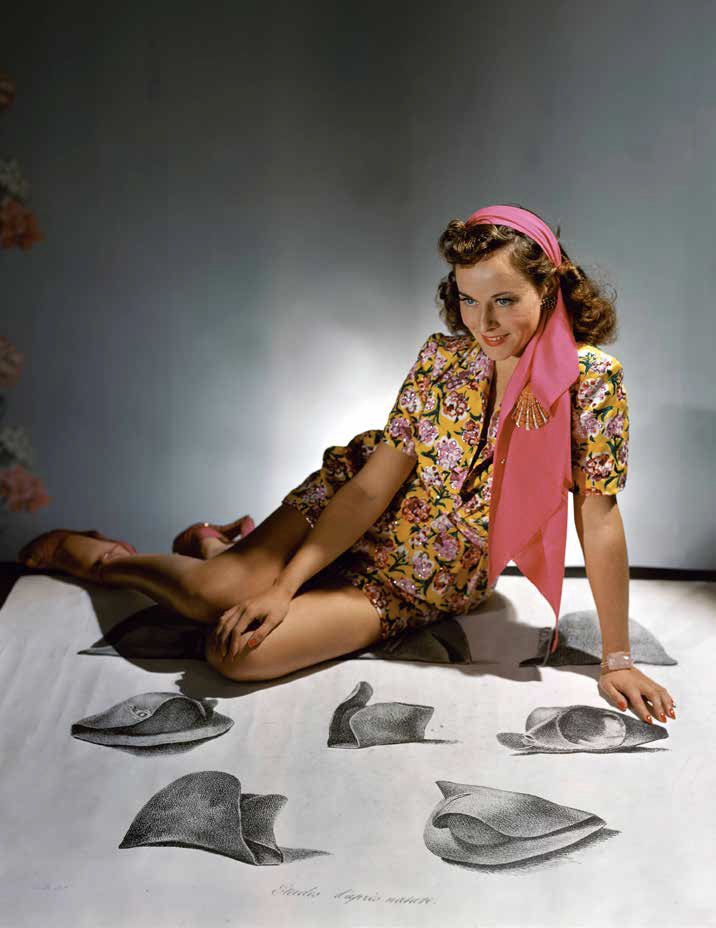

February 7, 2021Lions and tigers and bears, and countless other creatures, have been depicted in jewelry throughout history. Animals have contributed striking silhouettes and a dramatic sense of narrative to the art form. Long a subject of human fascination, they have often been represented in amulets meant to protect and guide us. In ancient Greece, snakes signified eternal love and wisdom. During the Renaissance, felines, ferrets and parrots — possibly heraldic totems — were rendered in enamel and pearls.

As a jewelry historian and the author of several books on 20th-century jewels, I began to study a corner of the vast world of animal jewelry a couple of years ago, when New York’s American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) invited me to guest curate a special exhibition to coincide with the opening of its Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals. The launch, although delayed by the pandemic and now scheduled for this spring, dovetails with the museum’s 150th-anniversary celebrations.

The new rooms are renovations of existing halls conceived in the 1970s and will include a space dedicated to temporary exhibitions. Two highlights among the more than 5,000 unmounted minerals and gems in the museum’s collection are the dazzling Star of India — a 563-carat star sapphire — and the 632-carat Patricia emerald. The holdings also include a select few pieces of jewelry, intended to show what creative minds do with the earth’s treasures on permanent display.

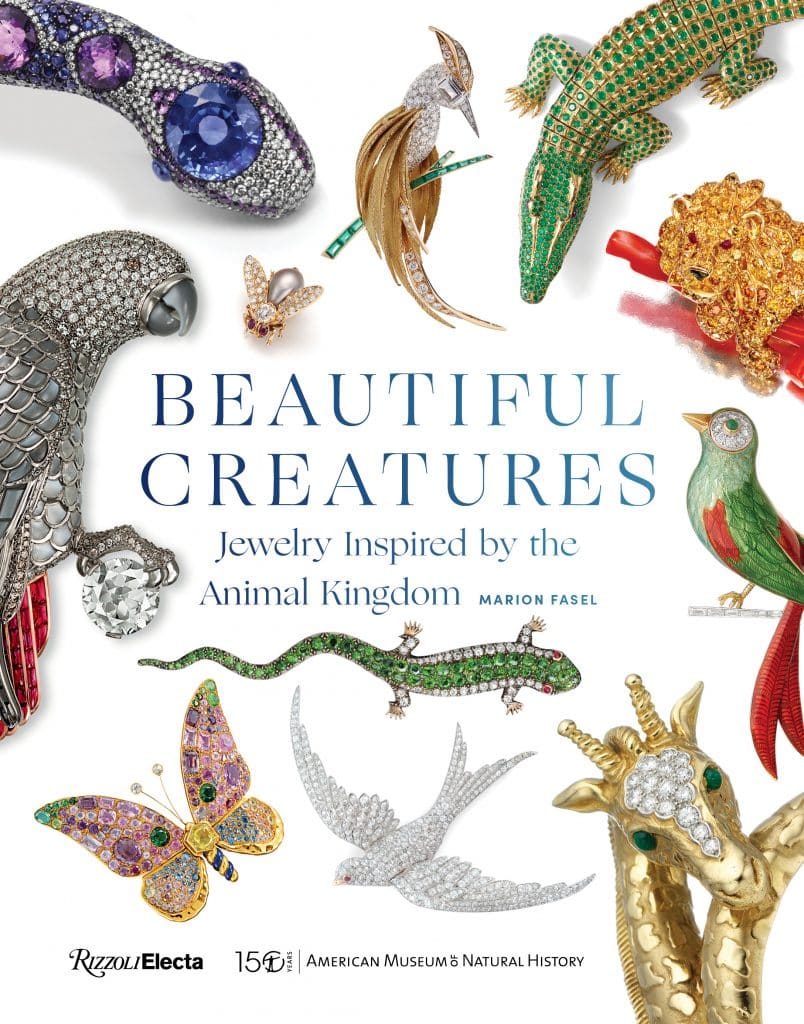

The inaugural temporary exhibition, “Beautiful Creatures: Jewelry Inspired by the Animal Kingdom,” along with the companion book from Rizzoli Electa detailing my research on the subject, focuses on gems made from 1869, the year the museum was established, through the present.

The wildlife in the institution’s famous dioramas suggested one of my first parameters for the exhibition. I decided that all the animals depicted in the jewels had to exist elsewhere in the museum. So, I left out barnyard and domestic beasts. And I didn’t include animals dressed as people.

When I explained this last rule to the museum’s science experts, they looked at me quizzically, as if to say, “Why would there be any animals dressed as people?” But such pieces have constituted a subgenre of animal-themed jewels over the past 150 years, albeit one that would take the show off course. My thinking was that once you add a mouse in a sailor suit or a hen in a hat, you have an entirely different presentation.

The elusive designer of the JAR collection, Joel Arthur Rosenthal, revealed that while he was growing up in New York City, he spent a lot of time in the museum’s Hall of Gems and Minerals.

Many people have asked how I found the more than 100 pieces in “Beautiful Creatures” and how long it took. The truth is it took me 30 years, plus 9 months.

Over the course of the nine months I had to secure the jewelry, I reached out to just about every contact I had worked with during my three-decade career. I was looking for jewels I had seen and knew were out there somewhere. I was also searching for treasures that had never been exhibited publicly.

Among the extraordinary jewels I came to include, many reflect historical events. One striking example is the carved-emerald, sapphire and diamond kingfisher brooch made by Cartier during the World War II occupation of Paris by German forces. Birds were viewed by the French as a symbol of hope during the war, and the kingfisher represented peace and prosperity.

During the same period, Cartier also famously created brooches in the shape of a small caged bird, set with gems representing the red, white and blue colors of the French flag. When the Gestapo questioned the house’s creative director, Jeanne Toussaint, about the design, she claimed it was an old one. It wasn’t. After the war, the jewel was redesigned with the bird singing and the cage door open.

Some of the most realistic animal pieces in the exhibition are insect jewels dating to the end of the 19th century. Their makers were responding to the general public’s obsession at the time with entomology, which they learned about at institutions like the AMNH and from gorgeously illustrated books. Two particularly stunning examples in “Beautiful Creatures” are an emerald and gold leaf weevil brooch made by Tiffany around 1893 and a Boucheron ruby, diamond and gold stag beetle brooch from around 1895.

The displays in the museum itself have been sources of inspiration for designers over the past 150 years. In 1941, for example, Fulco di Verdura fell in love with the cases of seashells and purchased several lion’s paw shells in the gift shop.

He took them back to his Fifth Avenue studio, where he had his craftsmen set the striations with gold, diamonds and sapphires to create the appearance of waves receding from the surface. The designer saucily explained to The New Yorker, “What I get a kick out of is to buy a shell for five dollars, use half of it, and sell it for twenty-five hundred.” He never revealed how hard it was to manufacture the designs.

In a rare interview, the elusive designer of the JAR collection, Joel Arthur Rosenthal, revealed that while he was growing up in New York City, he spent a lot of time in the museum’s Hall of Gems and Minerals. His passion for unusual and colorful stones is evidenced by the Montana sapphires of various blue hues covering the wings of a butterfly brooch he made in 1987. The body of the insect is set with an antique-cushion-cut diamond surrounded by smaller light-pink diamonds.

Some of the most iconoclastic and masterful pieces in the show were inspired by personal stories or special commissions. Among these is a version of the jellyfish brooch Tiffany designer Jean Schlumberger created in 1967 to ease his client and dear friend Bunny Mellon’s pain after she was stung by one of the marine animals while swimming at the Mill Reef Club in Antigua.

The bell-shaped top of Schlumberger’s La Méduse is covered in moonstones, gems with a subtle iridescence that echoes the bioluminescence of some jellyfish. The creature’s curled oral arms are made of chased gold and lined with various sizes of baguette-cut sapphires. A spring inside each of the six-inch-long gold tentacles allows them to move as though through water.

According to legend, film star María Félix waltzed into the Cartier boutique on the rue de la Paix in Paris around 1975 with live baby crocodiles. She let the jeweler know that she wanted a necklace inspired by the animals and that she took the concept seriously.

Cartier sculpted two crocodiles, complete with scutes like those found on the reptiles’ skin. One is covered in yellow diamonds totaling 60.02 carats; the other, in 1,060 emeralds totaling 66.86 carats. Both are entirely articulated with interior armatures. They can be joined together as a necklace or worn individually as brooches.

Jewels, especially those displayed in museums, are often seen as symbols of power and wealth. I believe the birds and beasts in “Beautiful Creatures” demonstrate that there is much more artistry and meaning to jewelry than conveyed by that one-dimensional point of view. I hope the exhibition instills in people — especially children, who make up such a large portion of the museum’s audience, and all the animal lovers among us — a sense of wonder and joy.