February 13, 2013Together with his wife, Paulien, and daughter, Tara, Schot rides in a 1958 German ‘’Munga’’ from Auto Union, which a year later became Audi. Top: In a part of the factory-cum-warehouse that Schot left untouched, his indoor “garden” is watered via a leak in the roof.

In the late 1990s, Joop Schot was selling computers to the first generation of online brokers and traders in Holland when he met a vintage-design dealer from Antwerp. Schot mentioned that his sister-in-law wanted to sell a classic 1950s wall-mounted teak Royal shelving system by the famous Danish mid-century modern designer Poul Cadovius, and a couple of weeks later, the dealer sold it for 400 guilders, or about $250 at the time. (These days, the same unit would go for about $3,000.)

That was a lot of money for something you got for free,” Schot recalls, explaining that when his sister-in-law bought her house, the Cadovious system came with it. “I thought, ‘That’s much better than selling computers.’ And I just rolled into it. I’m not really an office guy.”

These days, his “office” is a 16,000-square-foot converted factory — built in 1928, it once made caramel and the Dutch licorice called dropje — in Bergen Op Zoom, the Netherlands. Here he spends more than just working hours with his energetic Jack Russell terrier, Jenny, and two prehistoric-looking Mexican walking fish. (“Their limbs regenerate if they get pulled off,” he boasts.) But it’s the 10,000 pieces of Dutch, Italian and Scandinavian furniture and lighting from the 1950s to the ’70s, stacked from floor to ceiling on wide metal shelves, that really fill the ample, airy space.

He uses the war-scarred original section of the building (note the bullet holes in the walls), with its slightly crumbling white plaster and dramatic skylights, as a showcase for such individual prize pieces as an elegant, handmade Hans Wegner Keyhole oak-and-cloth rocking chair from 1967, a Cees Braakman 1962 President desk made of boomerang-shaped teak on steel feet and a 1970s glass-topped French coffee table with an illuminated brass-and-gemstone beetle-shaped base by French sculptor Jacques Duval-Brasseur.

Schot recently bought a 1902 villa near his warehouse, which he uses as a showroom for some of his prized items, including a Mario Bellini Camaleonda sofa in cream leather from 1971.

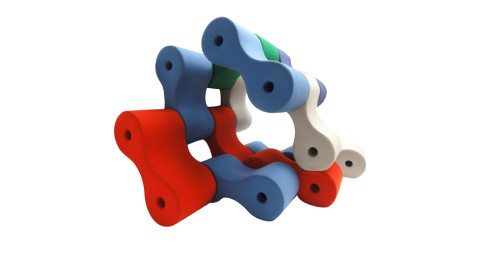

In the airplane-hangar–sized postwar portion, under a tin roof in the back, there are dozens of Mario Bellini’s marshmallow-like, modular Camaleonda sofas and Artifort easy chairs in eye-popping primary colors, plus scores of 1950s industrial office chairs and desks by Dutch creatives including Wim Rietveld and Friso Kramer, as well as industrial bar stools and machinist chairs made by Swiss designers. Among the stacks of modulars and multiples, one can spy surprising one-off pieces, like a rare, honey-colored leather 1970s Anfibio sofa by Alessandro Becchi, which resembles a giant folded baseball mitt, or a collection of baby blue, cloth-covered pews designed for a chapel made by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Schot regularly schedules lectures and educational design symposiums in this soaring space.)

After his initial serendipitous introduction to the business of design-dealing, Schot got his hands on a 1958 copy of the Dutch design magazine Goed Wonen (“Good Living”). “It all came together for me when I saw that,” he says. “All these great designers in one place. That was really an eye-opener.”

To educate himself further, Schot started visiting other design galleries. He went to Los Angeles to meet Joel Chen, whom he calls “the godfather of vintage design;” to Chicago to meet Richard Wright, founder of Wright auction house; and to Hudson, New York, to learn from dealer Mark Frisman. He also started collecting auction catalogues and attending design auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in Amsterdam, London and New York.

“I’m not really a reader type, but when I get information, I store it quickly,” he says. “You also learn a lot by just dealing. Every day is like going to a university to study.”

“I’M NOT REALLY A READER TYPE, BUT WHEN I GET INFORMATION, I STORE IT QUICKLY,” SCHOT SAYS. “YOU ALSO LEARN A LOT BY JUST DEALING. EVERY DAY IS LIKE GOING TO A UNIVERSITY TO STUDY.”

A rare set of Pamplona chairs by Augusto Savini for Pozzi, 1965, and several Wim Rietveld floor lamps for Gispen, 1954, are on offer at Joop Schot’s Art Broker Design in Bergen Op Zoom, the Netherlands.

He bought his first pieces on Marktplaats, the Dutch equivalent of eBay, and at auction houses, all while developing a network of contacts in Holland, the U.S., France and Italy.

Early on, Schot decided to focus on Dutch postwar designers. His attraction, he says, stemmed from a little bit of Dutch pride: “You can see these designers as a reflection of the rebuilding of Holland after the World War. For several years nothing happened. Everything was destroyed, and then these designers came along, and they all used the new techniques for innovating,” he explains. “Then you had the World Expo in Brussels, in 1958, and there was a Dutch pavilion with all the big designers: Friso Kramer, Gerrit Rietveld, Karel Appel. If you see those pictures it was like the atomic age and new science — everything was booming. It was kind of a rebirth.”

Many of the Dutch designers he admired found inspiration in the country’s De Stijl art movement, made famous by Piet Mondrian’s grids, primary colors and geometrical shapes. They also borrowed heavily from Scandinavian designers of the mid-century, such as Arne Jacobsen and Fritz Hansen, using teak, molded plywood and other warm-hued woods along with natural textured fabrics. Often they combined those influences with architectural furniture concepts from Americans Charles and Ray Eames.

What Schot especially favors are pieces that have a sturdy, industrial purity and utility — chairs with steel legs and fiberglass seats, say — but that also feel optimistic, with bright colors, clean lines and modular flexibility. Along with works from the mid-century, Schot has collected some recent Dutch pieces, including iconic works by Tejo Remy and René Veenhuizen, stars of Droog, the Amsterdam-based contemporary furniture design collective.

Schot sits in a Saar chair created by his former apprentice, Jorrim Kox, who now works as his restorer while attending the Design Academy in Eindhoven.

Among all the designers he represents, though, Schot has become most entranced by the work of Friso Kramer, a pioneer of Dutch industrial furniture who is known for items — school chairs, drafting tables — so ubiquitous that they hardly even register as design in Holland anymore. After attending a Sotheby’s Amsterdam auction of Kramer’s work in 2006, Schot simply looked up the designer in the phone book and gave a ring. To his surprise, Kramer invited him over for coffee, and they ended up talking for hours, and they remain in regular contact. Over the years, Schot presciently collected many examples of Kramer’s famous Revolt chair, whose painted molded-plywood seat and powder-coated folded steel legs on push-fit rubber feet became classroom mainstays, as well as his matching Reform conference or dining table, whose simple aluminum-edged linoleum top sits on folded sheet-metal legs. With Kramer’s help, Schot has also curated exhibitions of the designer’s work in Paris, Zurich, Ghent and Paris (where Galerie Catherine Houard is showing his pieces through March 2).

It’s paying off now, because Kramer is becoming very popular,” says Schot. “If something comes up on Marktplaats today, it just goes straight to Paris. His work is purely functional, no ‘extra bullshit’, as he would say. I am on a mission to show the rest of the world his no-nonsense design.”

Kramer is emblematic of what catches Schot’s eye. “What I like is when you see the quality in the piece, the beauty of the construction,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be a big master; it can be beautiful or ugly.”

Visit Art Broker Design on 1stdibs

TALKING POINTS

Joop Schot shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces.