April 20, 2025Architect Annabelle Selldorf has achieved a quiet sort of fame. Although not exactly a household name, to pretty much everybody in the worlds of design, art and culture, she is renowned for, appropriately enough, the subtle elegance of her work.

“I don’t speak very loudly,” says Selldorf, seated in her office, in Manhattan’s Union Square, on a red leather Union chair — a piece of her own design, from her Vica collection. “But I’m not indecisive. I don’t lack confidence.”

As a rule, she says, “I don’t want to do anything unnecessary. But every gesture that we do make should have quality and character.” For an example, one need look no further than her line of furniture. With their intimate proportions and beautifully integrated nods to mid-century modernism and classical forms, her pieces demonstrate a keen sensitivity to scale.

Selldorf’s trademark light touch makes her especially suited to sensitive renovations of, and additions to, existing buildings, especially historic ones. A recent glowing example — on which she collaborated with the firm Beyer Blinder Belle — is the thoroughly refreshed and transformed mansion housing the Frick Collection, on New York’s Upper East Side. Selldorf’s remastering of one of the world’s most beloved jewel-box museums — which took years to complete and cost $220 million — has just opened to the public.

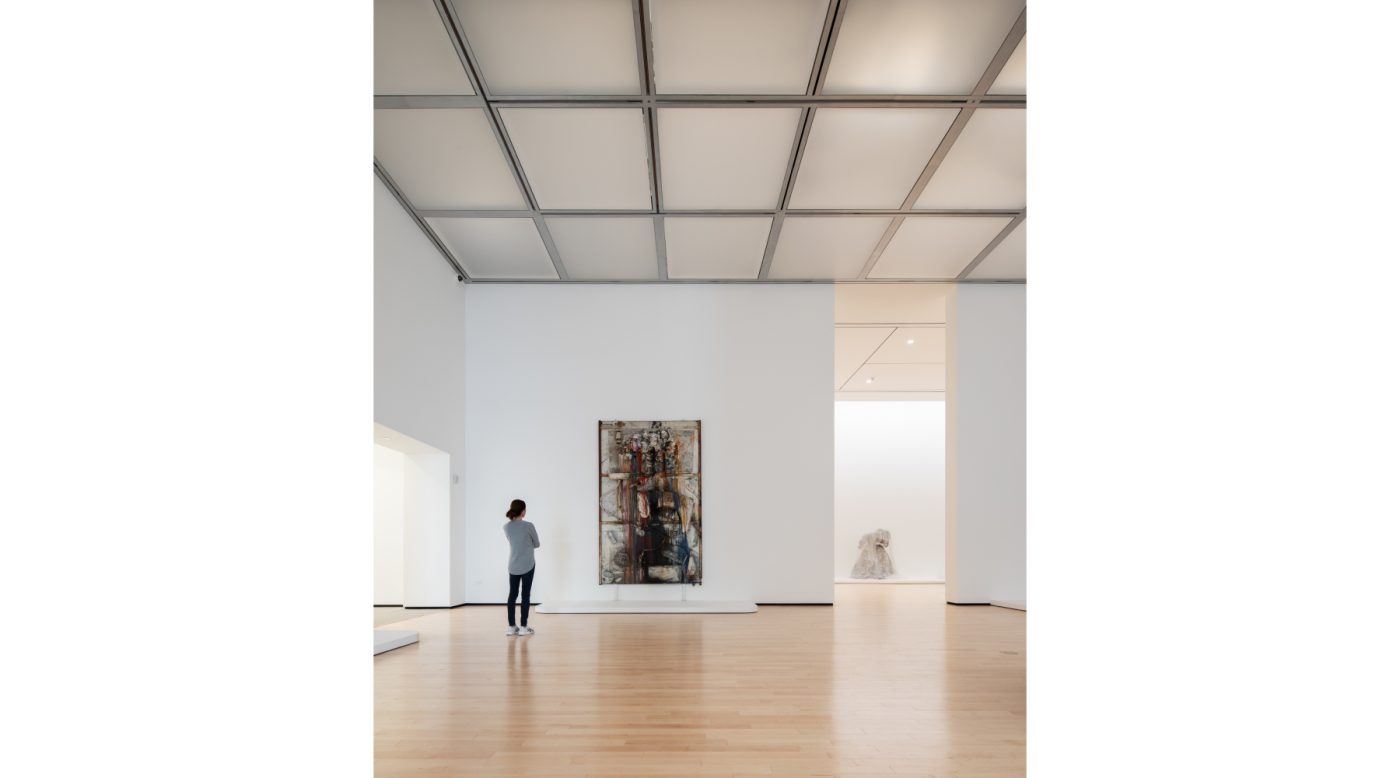

Selldorf has made her mark on many other cultural institutions, renovating the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, designing the new home of Miami’s Rubell Museum and directing the ongoing revamp of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her update of the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery (a 1990s design by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown) opens on May 10. And she is working now on a freestanding new building for the Clark Art Institute, in Massachusetts’s Berkshires, due to be completed in a few years and intended to house the Old Master treasure trove of the late collector Aso O. Tavitian.

But the Frick — housed in Gilded Age industrialist Henry Clay Frick’s 1914 Carrère & Hastings mansion, which was later expanded by John Russell Pope — is special. That’s because of the depth of its Old Master holdings (works by Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt van Rijn and other treasures, many collected by Frick himself) and the high expectations for the project.

“People care about the Frick the way they care about few other places,” Selldorf says. So, it was critical to the project’s success not to upset the institution’s legions of fans with anything too jarring. But this is Selldorf’s superpower.

Her brief from the Frick was to respect the original architecture, and its landmark status, while providing more space for art and, perhaps even more crucially, for people to actually move around the collection and even linger on their journey. Amazingly, the footprint has not changed at all.

“The new pathways we created feel like they’ve always been there, and that’s the hardest thing to do,” Selldorf says of giving visitors a viable circulation route through the museum for the first time. “You never feel like, ‘Where am I supposed to go?’ ”

She expanded the dimensions of the Frick in multiple ways that might seem small on their own but make a big difference when taken together.

Her biggest gesture was to raise the Reception Hall’s roofline seven feet, creating a true second floor in that part of the building. That now leads into new galleries in the mansion’s never-before-open upstairs bedrooms and adjacent spaces.

The Reception Hall’s street level, formerly crowded and awkward, is now anchored by a breathtaking cantilevered staircase in marble that you’ll see in many Instagram posts this spring (and a new elevator makes it truly accessible for visitors of all abilities).

The Frick’s interior square footage increased by 10 percent, but the gallery space grew by 30 percent. On that newly open second floor are smaller galleries, including one room showing off a charming collection of clocks. The Boucher Room is the former sitting room of the industrialist’s wife, Adelaide, now restored to its original status as a place where François Boucher paintings mix with Sévres porcelain. Frick’s own wood-paneled bedroom, now the Walnut Room, contains stellar portraits by the likes of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and George Romney.

The museum also got a 218-seat auditorium, cleverly located underground, and its first-ever café. (Opening this summer, it will have interiors by the Irish-born, London-based designer Bryan O’Sullivan, who once worked for Selldorf.)

Selldorf is masterful with residential work, too, and the connections of that skill set to the Frick — which started out as a house, after all — are rich.

“I have the privilege to do both, and one definitely informs the other,” she says. “Doing a lot of cultural work affords you the chance to think about the big picture. With residential work, there’s a reprieve of sorts. You can think about the object or the material.”

You might say domestic design is in her blood. Her father was an architect, most of whose work was residential, and her interior designer mother worked with him, says Selldorf, who grew up in Cologne, Germany, but has called New York home for decades.

She points out that Frick didn’t exactly build himself a regular house 101 years ago. It was always conceived as a semipublic place in which to show off his treasures. “He didn’t think of himself as a private person,” she says. The Frick’s hybrid status thus plays to her strengths in both categories.

For the Sagaponack, New York, getaway of the art dealer Per Skarstedt, she created a relatively simple modernist volume with shades of the Bauhaus. It’s a neat and tailored update of the modernist houses in the area. But by cladding it in dark mahogany-toned horizontal wood slats, she immediately distinguished it from other Hamptons residences, which tend to be white or a weathered light gray.

Selldorf is as much at ease with rough concrete as she is with wood, and she varies the materials she uses so much that you can’t look at a building she designed and immediately know it’s her handiwork.

But she does love marble. “She uses marble like a fabric,” says Lehmann Maupin Gallery’s David Maupin, who got plenty of it in the home Selldorf designed for him and his husband, magazine maestro Stefano Tonchi, in New York City’s historic Osborne, built in 1885.

Selldorf used marbles that subtly call out the colors of the Osborne’s original Arts & Crafts tilework in the kitchen, for the fireplace mantels and in the bathrooms (floor-to-ceiling-marble bathrooms are a Selldorf signature). Boldly hued Vica sofas, including the curvaceous Brubeck, further enliven the interiors.

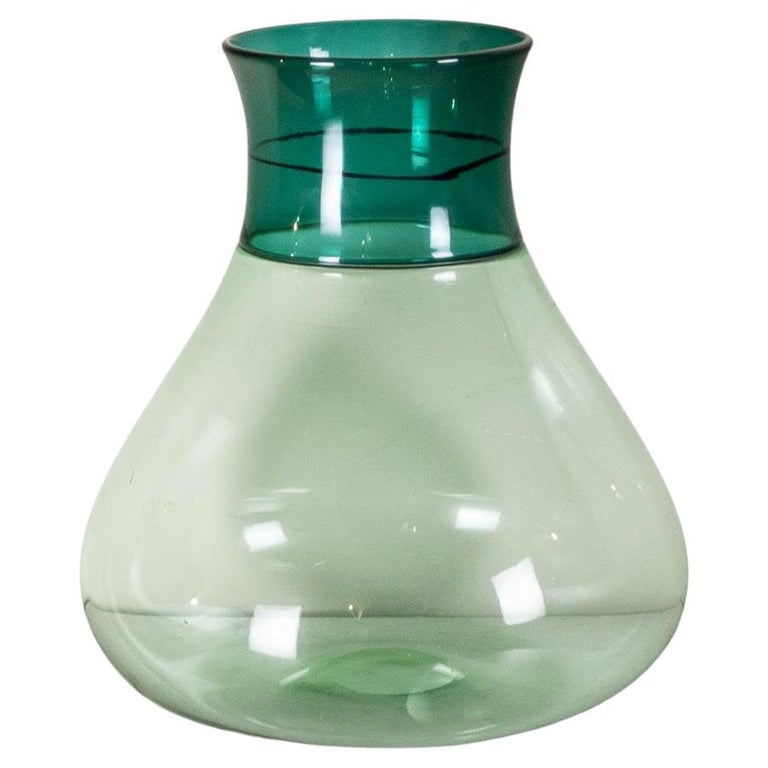

“Nobody plays with color like she does,” Maupin says. She also worked with Murano artisans on five large glass-and-brass chandeliers for the apartment. They took years to make, Maupin says, but they’re worth it.

Selldorf loves to address the minutiae of domestic life. “For me, residential work is about knowing how the clients like to have breakfast,” she says. And when it comes to aesthetics, she is not shy about asserting her point of view, if someone is insisting on erring against good taste. “Sometimes I do tell people, ‘No, you absolutely cannot do that,’ ” she says with a laugh.

Maupin concurs. “Most of the time we see eye-to-eye, but if we don’t, she’s right.”

In the dining room, certainly, great minds thought alike. The Teresita Fernandez wall installation Sfumato (Maupin Tonchi) — a 2016 commissioned work made of black graphite and magnets that completely encircles the room — provides visual pizzazz. And if seeing it on the walls doesn’t add enough oomph, the work is also reflected in the shiny tabletops, with their black mirror finishes.

The two striking tables can be combined, or not, to accommodate the varying ways Tonchi and Maupin entertain, and they also brought a “glamorous and special” air to the room, Selldorf says. Since she is friends with the couple, she also gets to be a user of the space, in addition to its designer.

Although she never sat at table with Henry Clay Frick, her many visits to the museum deeply informed how she improved it, answering her eternal question: “How do you move people around the space?”

As for supping in the Osborne with her clients, Selldorf confides that she allows herself a victory lap: “Everytime I go there for a dinner party, I think, ‘Wow that was really a good idea.’ ”