September 29, 2024The other day, I saw a jacked-up orange Jeep parked next to a corroding International Style tower in the seaside Connecticut city of Bridgeport. Emblazoned across the top of the windshield was an offensive and nonsensical rhyme about working hard and playing hard. My first thought was, Why would anyone put that on their car? My second thought was, Anastasia Samoylova would totally photograph this.

The multitalented Russian-born, Miami-based artist, who just turned 40, has become widely known for capturing the collision of built environments, natural habitats and odd subcultures, particularly in Florida. Think: crocodiles in swimming pools, moldering luxury high-rises, silhouettes of automatic rifles nailed to a soothing turquoise stucco wall, a gazebo consumed by vines.

Right now, her already bright star seems to be blazing.

Next month, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art will hang her works alongside those of another luminary who shot the Sunshine State in “Floridas: Anastasia Samoylova and Walker Evans.” Evans (1903–75) pioneered an aloof, sometimes funny style of American documentary photography that continues to influence lensmen and -women today.

Looking through the photographs in the show, it’s often hard to tell which belong to Evans and which to Samoylova. Often, the only giveaways are glimpses of 1960s cars and fedoras on passersby in an Evans photo or a higher degree of deterioration in the signage and pastel facades in a Samoylova composition.

The group show “Her: The Great Women Photographers,” up through November 23 at Peter Fetterman Gallery, in Santa Monica, California, places Samoylova among 20th- and 21st-century female masters of the craft, including Lillian Bassman, Berenice Abbott, Ruth Bernhard, Eve Arnold, Mary Ellen Mark, Nikki Kahn and Sarah Moon.

“What’s amazing about Anastasia’s work,” says the gallery’s eponymous owner, “is that she is on the cutting edge of great innovative contemporary photography but at the same time is steeped in the history of photography.”

The new monograph Adaptation (Thames & Hudson) brings together her many series of photographs, collages and paintings, with essays by Met curator Mia Fineman, critic Lucy Sante and writer David Campany.

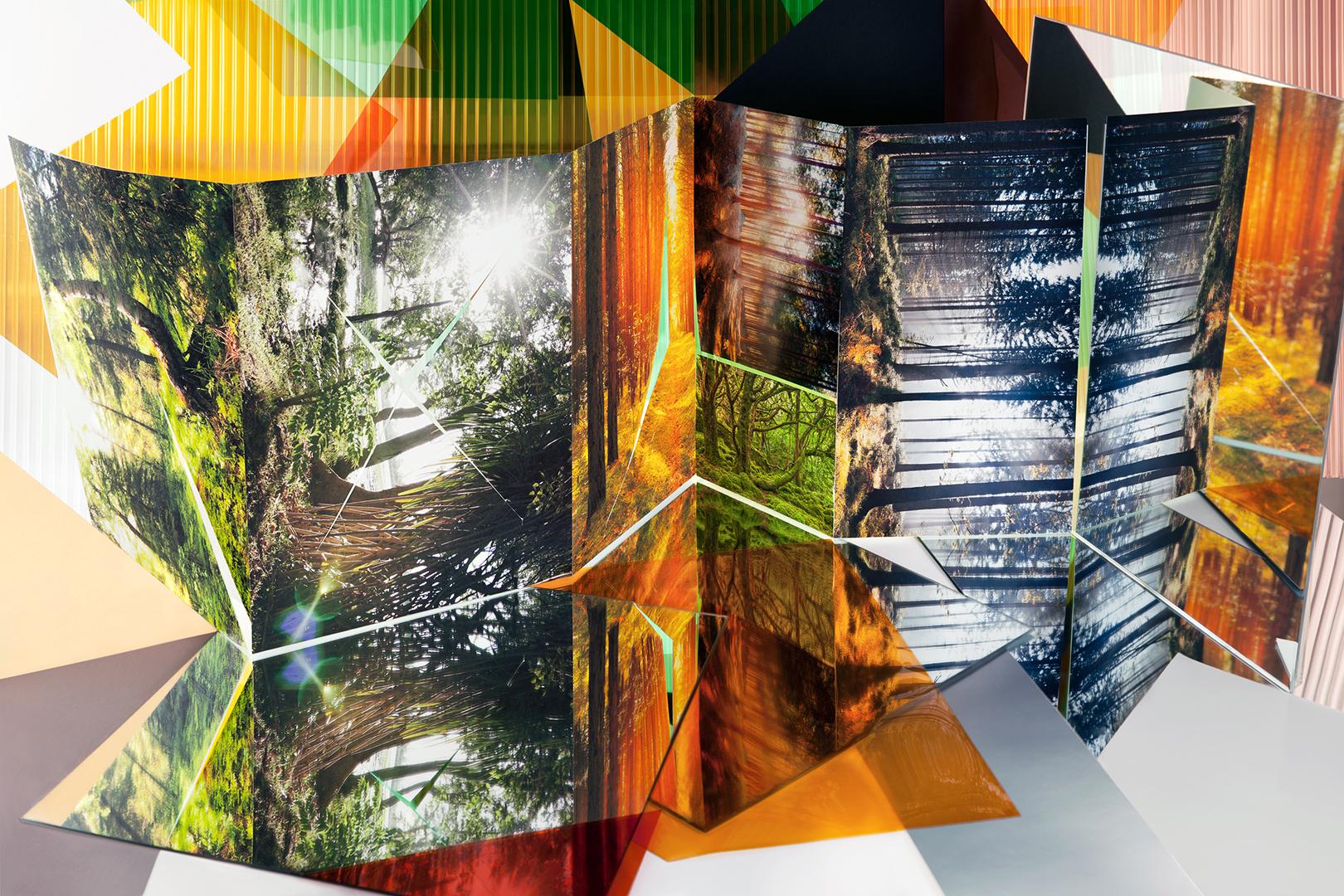

Beyond the numerous Florida-themed creations, the book highlights Samoylova’s ongoing “Landscape Sublime” (2013–), in which she collates photos culled from Flickr — with thematic subjects like trees in fog, arcing rainbows, fractal lightning bolts — into delightfully disorienting Cubist and Constructivist collages.

The photos in “Image Cities” (2021–22) reveal how giant ads plastered on buildings create a generic, late-capitalist sameness in metropolises the world over, making it difficult to tell the difference between Tokyo, Toronto, Mexico City and Monaco.

“Breakfasts” (2017–) feels more intimate, pairing still lifes of lattes, pastries, smoothies and fruit with closeups of art from coffee-table books by Edward Hopper, Ilse Bing, William Eggleston, David Hockney and the like.

Introspective caught up with Samoylova in the middle of shooting her latest project, “Atlantic Coast,” which retraces Berenice Abbott’s 1954 photo trip along U.S. Highway 1, extending from northern Maine to the Florida Keys. The highway even passes through Bridgeport, where I saw the orange jeep.

Here, Samoylova tells us about this latest photoshoot, her migration to Florida and where she’ll travel next.

Why do you find Florida so compelling as an art subject?

Florida’s unique blend of natural beauty and artificial spectacle makes it endlessly photographable. Its landscapes are visually striking, with dramatic skies, lush vegetation and an ever-changing coastline. At the same time, there is this human layer — urban sprawl, tourism culture and environmental tension. The juxtaposition of the pristine and the constructed and the tension between preservation and overdevelopment create a rich visual narrative.

There is also something about the light in Florida — bright, sometimes harsh, always dramatic — that enhances the surreal quality of the environment. It is a place where contradictions coexist, and as a photographer, it is irresistible to explore those layers.

Say more about some of those layers.

Florida is often associated with nature — lush wetlands, endless coastlines, tropical flora and that intoxicating, ever-changing light. But beneath that surface beauty, there’s a palpable tension.

The relentless push for development has scarred large swathes of the land, and rising sea levels threaten entire communities. There’s a sense of impermanence here that feels almost dystopian — the constant risk of hurricanes, the looming reality of displacement due to climate change and the surreal, sprawling real estate development that seems to grow unchecked.

The tension between nature and development, beauty and fragility is what I explore in my work. Yet fragility has its own kind of beauty. It forces us to confront the fleeting nature of the world around us, the way landscapes and lives are in constant adaptation, much like the state itself.

How did you end up in Miami? Tell us about your geographic journey through life and art thus far.

I wouldn’t say I “ended up” in Miami. That phrase implies a kind of inevitability or a lack of choice, which doesn’t really capture the energy of this place, especially with the mass migration into Florida in the last few years. It’s a highly desirable location now, with a dynamic cultural scene — and, for me, a place that aligns with the themes I explore in my work.

I was born in south Russia, closer to Georgia than Moscow, but I grew up in Moscow from age five. Something about the American South feels familiar to me, almost as if it’s part of my personal geography — warmth, light and the breadth of landscapes stretching across the horizon. My geographic journey has always had this duality: from the structured, urban environment of a densely populated city to more sprawling spaces, like lowlands and wetlands.

My art career has mirrored this journey, from traditional documentary photography to more experimental, collage-based work. Moving to Miami has allowed me to engage with ideas about the built environment, nature and image making on a much broader, almost global scale. The city itself is a collage of cultures, architecture and identities, and I find myself constantly inspired by its contrasts.

Regarding the upcoming Met show, what has Walker Evans’s art meant to you? And can you talk about other artists or movements that have influenced your work?

Walker Evans has had a profound impact on my work, especially in the way he used photography to capture the essence of American life. I greatly admire his ability to document with such clarity and subtlety without imposing a didactic narrative. His photographs reveal so much about the social and cultural landscape, yet they leave space for viewers to draw their own conclusions.

This sense of openness and restraint is something I’ve carried into my own practice, especially in projects like “Floridas,” where I explore the layers of myth and reality in the American landscape, much like Evans did in his work.

Beyond Evans, I’ve been influenced by a range of artists and movements, particularly those tied to the early modern period. Constructivism, for example, has informed the way I think about structure and composition. There’s a rigor and geometric precision in constructivist art that resonates with my approach to photography, especially when dealing with architectural forms or urban landscapes, as I do in the “Image Cities” or “Landscape Sublime” series.

In my new survey book, Adaptation, you can see how these historical influences intersect. The book examines how images adapt and evolve in the digital age, constantly being repurposed, recontextualized and reinterpreted.

What’s the continuity between your photographs, collages and paintings?

It’s a combination of several elements — but most importantly, it’s the way I approach the subject matter and the framing, as I tend to work with dense compositions, layering imagery to create a sense of complexity and depth. My color palette often reflects the lush, vibrant and sometimes overwhelming quality of the contemporary human-intervened landscape. Regardless of the medium, I’m always exploring the relationship between the built environment and nature, the tension between reality and representation.

With observational photography, I can capture the immediacy of what’s in front of me, whereas collages and paintings let me manipulate that reality further, creating hybrid spaces that speak to our experience of living in both physical and mediated environments.

You started “Image Cities” in 2021. Was that because you became a U.S. citizen, which opened up more travel opportunities for you? Will your work become more internationally focused moving forward?

While it’s true that becoming a U.S. citizen in 2021 did offer a lot more flexibility in terms of travel, the inception of “Image Cities” wasn’t directly tied to that.

The project grew more out of my ongoing interest in the visual language of cities and how global metropolises communicate through their architecture, advertising and various images in public spaces. Urbanization, image culture and climate change are universal issues, and I’m committed to exploring these topics in more locations around the world.

You told me you’re in the middle of a photoshoot. Can you share a little about it?

I’m currently working on “Atlantic Coast,” a project inspired by the pioneering work of Berenice Abbott, who in 1954 set out to document U.S. Route 1 from Maine to Florida. I’m retracing her steps but in reverse — from my home in Florida up to Maine — exploring the dramatic transformations that have taken place since Abbott’s time.

My goal is to revisit the landscapes and communities she captured and reflect on how the relentless expansion of highways, industry and real estate has reshaped these places, often at the expense of local ecosystems and histories.

Through photography, I aim to chronicle these evolving landscapes, focusing on the contrast between the romanticized imagery of the American East Coast and the complexities of its current reality. The work will explore themes of environmental degradation, socioeconomic disparity and cultural identity, much like my previous projects but on a larger geographical scale.

Using color photography, in contrast to Abbott’s black-and-white, I intend to emphasize the layers of artifice and reality that define modern life along the coast. The project is still in its early stages, but I hope to complete the first edit by March 2025, with exhibitions planned at the Norton Museum of Art, in West Palm Beach, and the Johnson Museum of Art, at Cornell University, accompanied by a book with Aperture.